Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

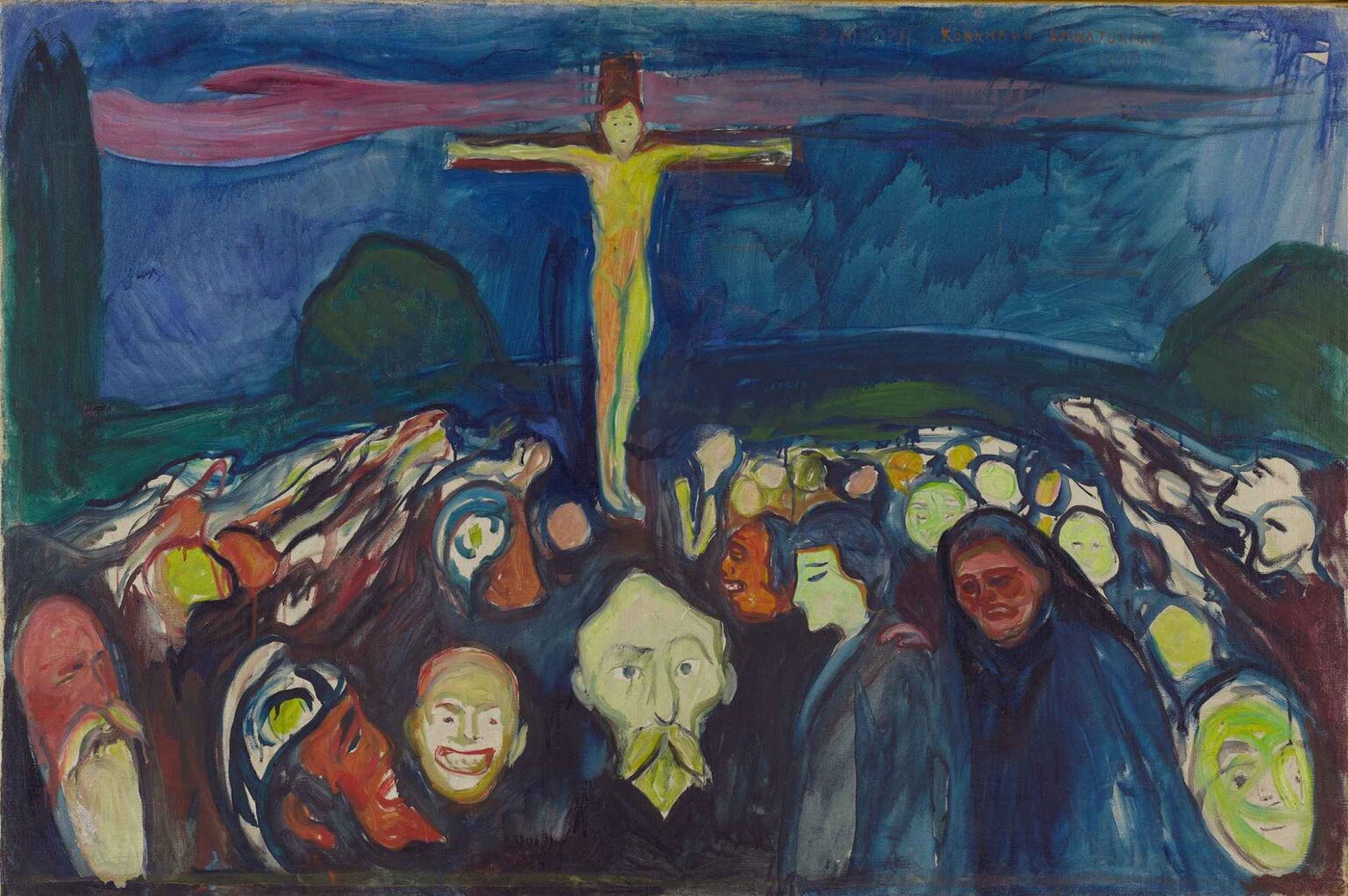

Edvard Munch’s Golgotha (1900) is among the artist’s most ambitious efforts to fuse religious narrative with raw psychological expression. Departing from conventional depictions of the crucifixion, Munch populates the scene with a tumultuous assembly of distorted faces beneath a solitary, crucified figure. The canvas pulsates with a restless energy: the rows of jostling heads, rendered in lurid hues, gaze upward at the illuminated form on the cross. Through his radical handling of line, color, and form, Munch transforms a familiar biblical event into a symbolic crucible of collective suffering and spiritual yearning. In Golgotha, the landscape becomes an arena of human anguish, and the divine figure floats between life and death, imbuing the painting with an unsettling tension that resonates far beyond its historical moment.

Historical Context

At the turn of the 20th century, Europe stood at a crossroads of artistic innovation and spiritual questioning. Munch, born in 1863 and shaped by early encounters with illness and loss, had already established himself as a voice of Symbolist anxiety with works like The Scream (1893) and The Madonna (c. 1894–95). Religious iconography had long been part of his visual vocabulary, yet he approached sacred themes not as an affirmation of dogma but as a means to explore the inner life—desire, dread, redemption. In 1900, the influence of Nietzschean philosophy and the decay of traditional religious structures weighed heavily on European consciousness. Golgotha emerges from this milieu: it is both a meditation on sacrifice and a commentary on the human impulse to seek transcendence amid existential despair. By reinterpreting the crucifixion through his subjective lens, Munch aligns himself with a broader fin-de-siècle search for new forms of spiritual expression.

Subject Matter and Iconography

The painting’s title, Golgotha, refers to the hill outside Jerusalem where Christ was crucified. Yet Munch’s interpretation refrains from historical accuracy. Instead of a distant, serene landscape, we see a deep blue void punctuated by swirling green masses—perhaps hills or rolling crowds—against which the cross stands starkly vertical. The crucified figure, positioned above the fray, is rendered in sickly yellow and pale flesh tones, suggesting both divinity and corporeal vulnerability. Below, an agglomeration of heads—some human, some masklike—press forward in a convulsive mass. These faces range from anguished to mocking, from pious grief to derisive sneers. Munch does not differentiate pilgrims from tormentors; all are united in a single human tide, implicating the viewer in the collective act of witness and judgment.

Composition and Spatial Structure

Munch organizes Golgotha around a central axis defined by the cross, which bisects the canvas vertically. This rigid structure contrasts with the horizontal undulations of the crowd and the subtle arc of the distant horizon. The viewer’s eye is first drawn upward to the crucified figure, whose outstretched arms echo the flat top of the painting and the sweep of a pinkish-red cloud in the sky. From there, the gaze descends to the churning mass of faces, which obliterate any sense of foreground or background distinction. There is no clear separation between observer and observed; the heads blend into one another, forming a living pattern that engulfs the lower half of the painting. Negative space vanishes beneath Munch’s dense application of pigment, creating a claustrophobic atmosphere that underscores the inescapability of the scene’s emotional force.

Color and Illumination

Color in Golgotha functions as a psychological agent rather than a naturalistic device. The deep cobalt blues of sky and landscape provide a somber, almost nocturnal stage. Against this backdrop, the cross and figure are painted in garish, high-contrast hues—lime green on the wood, pale yellow flesh—making them both luminous and ghostly. A horizontal band of rose-pink cloud, situated just above the crossbeam, suggests supernatural intervention or a rupture in the heavens. Below, the crowd’s heads blossom in cadmium reds, olive greens, and sickly whites, as if each face were lit by its own inner fire. Munch deliberately eschews subtle modeling; instead, he employs flat, unmodulated swaths of color punctuated by expressive outlines. The effect is one of electric tension: hues clash and resonate, evoking the tumult of collective grief and awe.

Technique and Brushwork

Executed in oil on canvas, Golgotha reveals Munch’s characteristic blend of precision and spontaneity. The crucified figure is delineated with relatively controlled strokes, its form carved out of the surrounding color field. In contrast, the crowd below appears in rapid, gestural dabs and swooping arcs, lending the scene a sense of frenzied movement. The canvas texture shows through in many areas, particularly in the sky, where thinly applied pigment allows the weave to become part of the image. Munch’s brushwork leaves visible traces of his hand: the flick of the wrist in a curved cheek, the imprint of bristles in a cloud formation. This painterly immediacy enacts the very emotion the painting seeks to convey, transforming the act of making into an intrinsic aspect of the work’s spiritual urgency.

Symbolism and Themes

At its core, Golgotha is a meditation on sacrifice, culpability, and communal redemption. The isolated figure on the cross embodies the archetype of innocence bearing the weight of collective sin. Yet by surrounding him with a throng of indiscriminate faces—mourning, mocking, indifferent—Munch suggests that humanity as a whole participates in both crucifixion and salvation. The blurred identities of the crowd point to the universality of the event: each member of the audience may recognize facets of themselves in those contorted visages. Moreover, the pink cloud that stretches across the sky can be read as a symbol of transcendence, a promise of resurrection inscribed amid the tumult. In Golgotha, Munch assembles a symbolic pantomime in which the boundaries between sacred and profane, victim and perpetrator, dissolve into a shared human experience.

Emotional and Psychological Resonance

The power of Golgotha lies in its capacity to evoke visceral responses without narrative explanation. Viewers often report heat rising to their cheeks or a tightening in the throat when confronted with the painting’s intense palette and concentrated mass of faces. This physical reaction parallels the existential tension at play: the simultaneous impulse to recoil in horror and to lean forward in recognition. Unlike traditional religious art that offers solace or reassurance, Munch’s vision is unsettling—yet it also invites communion. By exposing the raw mechanisms of empathy and projection, he enables a profound act of identification with both the suffering figure and the witness crowd. In this way, Golgotha functions as a psychic mirror, reflecting the viewer’s own capacity for both compassion and complicity.

“Golgotha” within Munch’s Oeuvre

Golgotha represents a pivotal moment in Munch’s exploration of religious themes and collective emotion. Earlier works such as The Passion of Christ prints and The Entombment had already shown his interest in biblical subjects. Yet in Golgotha, he takes the narrative out of its historical costume and infuses it with a modern psychological register. The painting also foreshadows Munch’s later series on death and eternity, including Vampire (1895–96) and Anxiety (1894), in which he continued to depict crowds and couples under the weight of existential dread. Furthermore, Golgotha anticipates Expressionist experiments in Germany, where artists like Franz Marc and Emil Nolde would similarly employ distorted forms and aggressive color to convey emotional truth. In this respect, the painting stands as both culmination and precursor—a nexus between 19th-century Symbolism and 20th-century abstraction.

Reception and Legacy

When first exhibited in Kristiania and later in Berlin, Golgotha generated polarized reactions. Conservative critics decried its departure from reverent religious imagery, while avant-garde circles acclaimed its courageous fusion of spirituality and modernity. Over the ensuing decades, art historians have come to view Golgotha as a landmark in the evolution of Expressionism and psychological portraiture. The painting has been included in major retrospectives of Munch’s work and cited in studies of art’s capacity to externalize internal conflict. Contemporary artists exploring themes of collective trauma frequently reference Golgotha for its prescient engagement with the dynamics of crowd psychology and sacrificial myth. Its legacy endures in the ongoing dialogue about art’s role in mediating the boundary between individual suffering and communal experience.

Conclusion

Edvard Munch’s Golgotha transcends its biblical subject to become a universal allegory of suffering, empathy, and redemption. Through a masterful synthesis of composition, color, and gesture, Munch constructs a scene that is at once specific and timeless—a depiction of crucifixion that speaks to every age’s capacity for violence and compassion. The isolated figure on the cross hovers above a heaving sea of human faces, reminding us that sacrifice and salvation are communal affairs. By stripping away historical detail and amplifying emotional resonance, Munch invites viewers into an encounter with their own hearts, challenging them to witness not only the divine but also the depths of their shared humanity.