Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

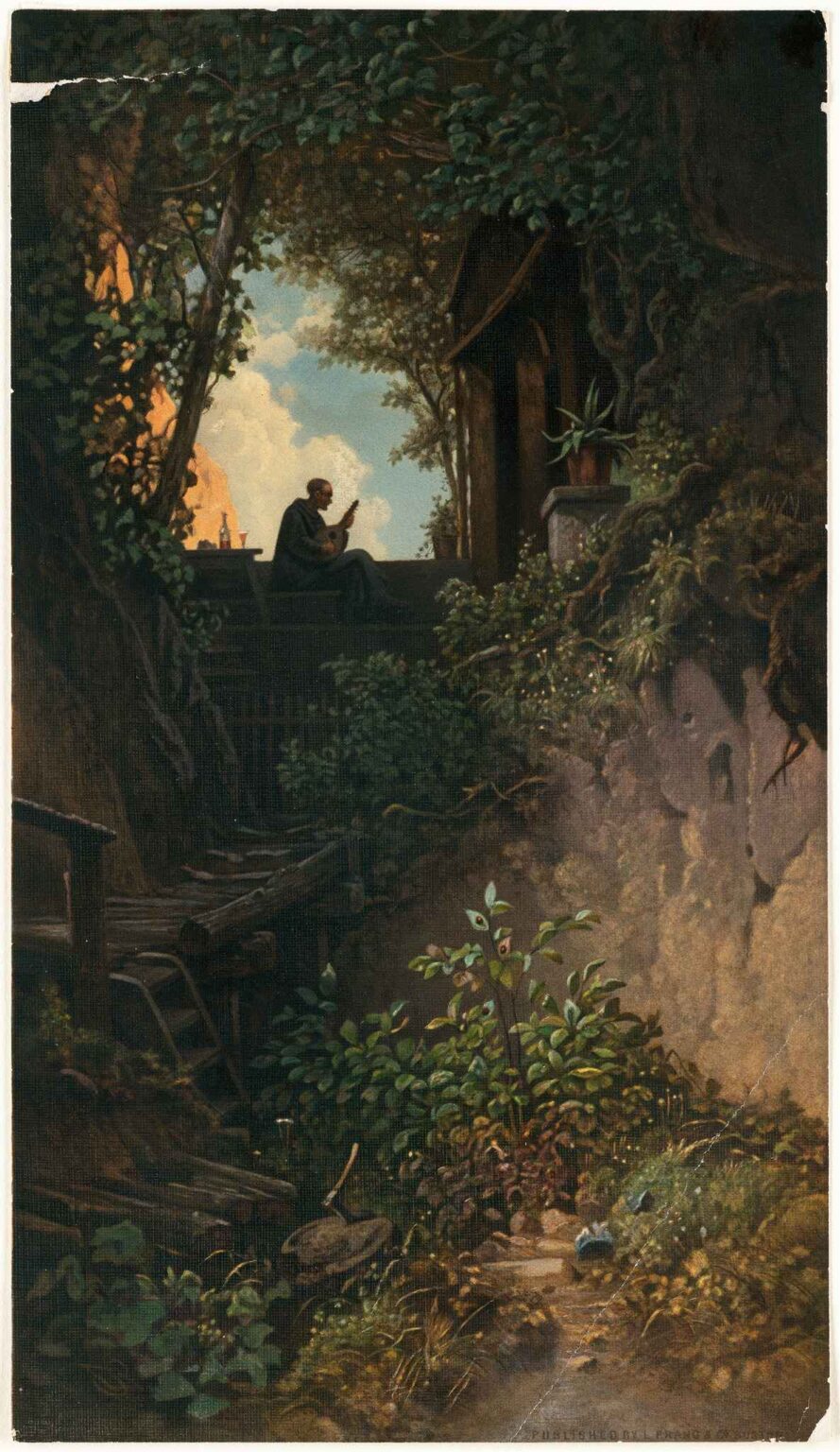

Carl Spitzweg’s Golden Evening is a masterpiece of quiet reflection, suffused with romantic melancholy and poetic solitude. Painted in the 19th century by one of Germany’s most beloved Biedermeier artists, the work captures a moment of introspection as a lone figure plays a lute in a shadowy, garden-like enclosure, embraced by nature and silence. With its delicate light, harmonious palette, and richly textured setting, Golden Evening embodies the themes central to Spitzweg’s oeuvre: individualism, harmony with nature, and the meditative beauty of simple moments.

Though small in scale and modest in subject matter, the painting evokes a profound emotional resonance. It speaks to the Romantic yearning for inner peace, the lost ideals of medievalism, and the healing power of artistic solitude. This analysis explores the painting’s historical context, visual structure, symbolism, emotional tone, and broader philosophical implications, demonstrating why Golden Evening continues to enchant viewers well into the 21st century.

Carl Spitzweg: Painter of the Poetic Everyday

Carl Spitzweg (1808–1885) was a German painter and poet associated with the Biedermeier period, a time defined by domesticity, introspection, and a retreat from the political turbulence of post-Napoleonic Europe. Trained initially as a pharmacist, Spitzweg turned to art in his late twenties, developing a style that combined the humorous observation of daily life with gentle satire and a deeply Romantic sensibility.

His works often depict eccentric individuals—hermits, scholars, artists—situated in richly detailed interiors or idyllic landscapes. Though sometimes whimsical, Spitzweg’s paintings are underpinned by a quiet philosophical depth. Golden Evening exemplifies this approach: its central figure is a kind of spiritual anchor, whose stillness reflects the sublime hush of the natural world around him.

Composition and Spatial Design

The composition of Golden Evening is vertically oriented, leading the viewer’s eye upward from a forested, rocky foreground to a higher plateau where the human figure sits. This structure reinforces the idea of ascension—not just physically up the slope, but spiritually toward enlightenment or tranquility.

At the top left of the painting, bathed in warm golden light, sits a solitary man, holding a lute. His silhouette is clearly visible against the sky, framed by a break in the forest canopy. A small table with a bottle and glass beside him suggests a scene of relaxed contemplation. The space around him is bordered by ancient stone structures and trailing vines, evoking a romantic ruin, perhaps even a hermit’s retreat.

In contrast, the foreground is darker, more overgrown, filled with detail—wild plants, mossy rocks, discarded objects. The careful delineation of these elements underscores Spitzweg’s precision as an observer of nature and human environments. The man appears physically distant, yet emotionally present, as if elevated by thought and melody.

Light and Atmosphere

Light is the defining feature of this painting. Spitzweg masterfully manipulates it to create an almost spiritual ambiance. The golden sunlight penetrates the leafy overhang at the top left, illuminating the figure and casting a soft glow over the scene. This creates a powerful contrast with the shadowed lower portion of the painting, where detail becomes denser and more mysterious.

This light is not merely decorative—it’s symbolic. The “golden evening” suggests the time of day when the sun lowers and casts everything in a honeyed radiance. But metaphorically, it may also reference the twilight of life or a moment of inner peace reached after struggle. The effect is serene, almost sacred, like an invocation of Romantic stillness.

The atmospheric depth adds to the contemplative mood. There’s a damp, almost aromatic richness to the shaded path below, while the airy upper section feels open and light. Spitzweg uses this interplay to guide the viewer from darkness toward illumination.

The Figure: A Portrait of Inner Life

The man with the lute is the focal point and emotional heart of the composition. Though his features are indistinct, his posture conveys solitude, ease, and introspection. He is not performing for others, but communing with himself—or with the natural world around him. The lute, historically associated with poetic expression and spiritual harmony, becomes a symbol of inner resonance.

His choice of setting reinforces his psychological state. This is no palace or concert hall, but a secluded natural amphitheater. The crumbling stone walls, thick vegetation, and modest furnishings suggest a life of simplicity, removed from the noise of society. In this way, he becomes a modern-day hermit or Romantic ideal of the artist: one who finds beauty in silence and creation in solitude.

Spitzweg often used such figures to explore the value of interiority in a world increasingly driven by industrialization and conformity. In Golden Evening, the man becomes an embodiment of peace achieved not through power, but through presence.

Nature as Companion

Nature in Golden Evening is not wild or threatening—it is tender, sheltering, and observant. Spitzweg renders every branch, vine, and leaf with care, suggesting a personal intimacy with the landscape. The environment seems almost to listen to the lute player, enveloping him in green and gold.

The flora in the foreground—rich with varied textures, earthy tones, and soft brushwork—contrasts with the smoother sky and light above. This reinforces the duality of human life: grounded in the physical but aspiring toward the transcendent.

The theme of nature as a gentle, nurturing presence reflects Romanticism’s reverence for the natural world as a source of emotional and moral truth. Spitzweg’s garden is not Edenic in the biblical sense, but it is a spiritual sanctuary where harmony between man and earth is possible.

Symbolism and Subtext

While Golden Evening does not contain explicit allegory, it is rich in symbolic nuance. The title itself hints at the passage of time—not only a daily cycle, but life’s progression toward a peaceful conclusion. This theme of temporality is reinforced by the figure’s age (likely elderly), the worn stonework, and the decay of the forest path.

The lute signifies poetic expression and perhaps nostalgia. Its gentle music is inaudible to us, but the painting encourages viewers to imagine it—a quiet, melancholic melody echoing through the glade. This imaginative invitation reflects Spitzweg’s interest in the personal, internal experience of art.

The stairs leading down and the elevation of the figure might also suggest a metaphorical ascent: from mundane reality to reflective transcendence. The vertical format and composition make this movement subtle but unmistakable.

Color Harmony and Texture

Spitzweg employs a restrained, earthy palette, punctuated by warm light and delicate greens. This color harmony enhances the mood of unity and peace. The golden sky blends softly into the greens of the trees, creating a cohesive atmosphere of evening stillness.

His brushwork is meticulous but not rigid. Textures are implied through layering and variation rather than detail for its own sake. The treatment of the foliage, especially, reflects a naturalistic yet painterly approach, allowing light to flicker through the leaves and dance across surfaces.

The careful modulation of color and texture serves both aesthetic and narrative functions: it builds atmosphere, guides the eye, and reinforces the painting’s emotional core.

Philosophical Underpinnings

At its heart, Golden Evening is a meditation on solitude, reflection, and the quiet fulfillment of a life lived in tune with oneself and the world. It embodies the Biedermeier ideal of the “inner world” as a sanctuary against the noise of modernity.

In contrast to the grand gestures of history painting or the theatricality of academic art, Spitzweg’s work suggests that beauty and meaning lie in the modest, the intimate, the overlooked. His paintings do not shout—they whisper.

This philosophical orientation aligns with German Romanticism, especially the writings of Friedrich Schlegel and Novalis, who saw in solitude not loneliness, but the opportunity for self-discovery and spiritual insight.

Reception and Legacy

Though Carl Spitzweg is often categorized as a Biedermeier artist, his later reputation grew among those who saw in his work a deeper emotional intelligence. In the 19th century, Golden Evening would have been appreciated for its craftsmanship and sentimentality. Today, it resonates as a visual poem—subtle yet profound.

Spitzweg’s ability to transform everyday scenes into moments of transcendence has ensured his place in the canon of Romantic painting. Golden Evening is a quintessential example: visually modest but emotionally expansive, precise yet full of suggestion.

The painting continues to inspire those drawn to quiet contemplation, artistic solitude, and the harmony between human and nature. In an age defined by digital noise and relentless productivity, Golden Evening offers a luminous alternative: the golden light of stillness.

Conclusion

Carl Spitzweg’s Golden Evening is a work of rare tranquility and poetic depth. Through masterful composition, luminous color, and intimate detail, the painting becomes more than a depiction of a man and his instrument—it becomes a portrait of inner peace, a hymn to nature, and a timeless evocation of the soul’s desire for harmony.

It invites us to pause, listen, and reflect—not as passive viewers, but as participants in the quiet magic of the scene. Whether seen as a Romantic meditation, a philosophical allegory, or simply a beautiful moment caught in golden light, Golden Evening remains one of Spitzweg’s most touching and resonant creations.