Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

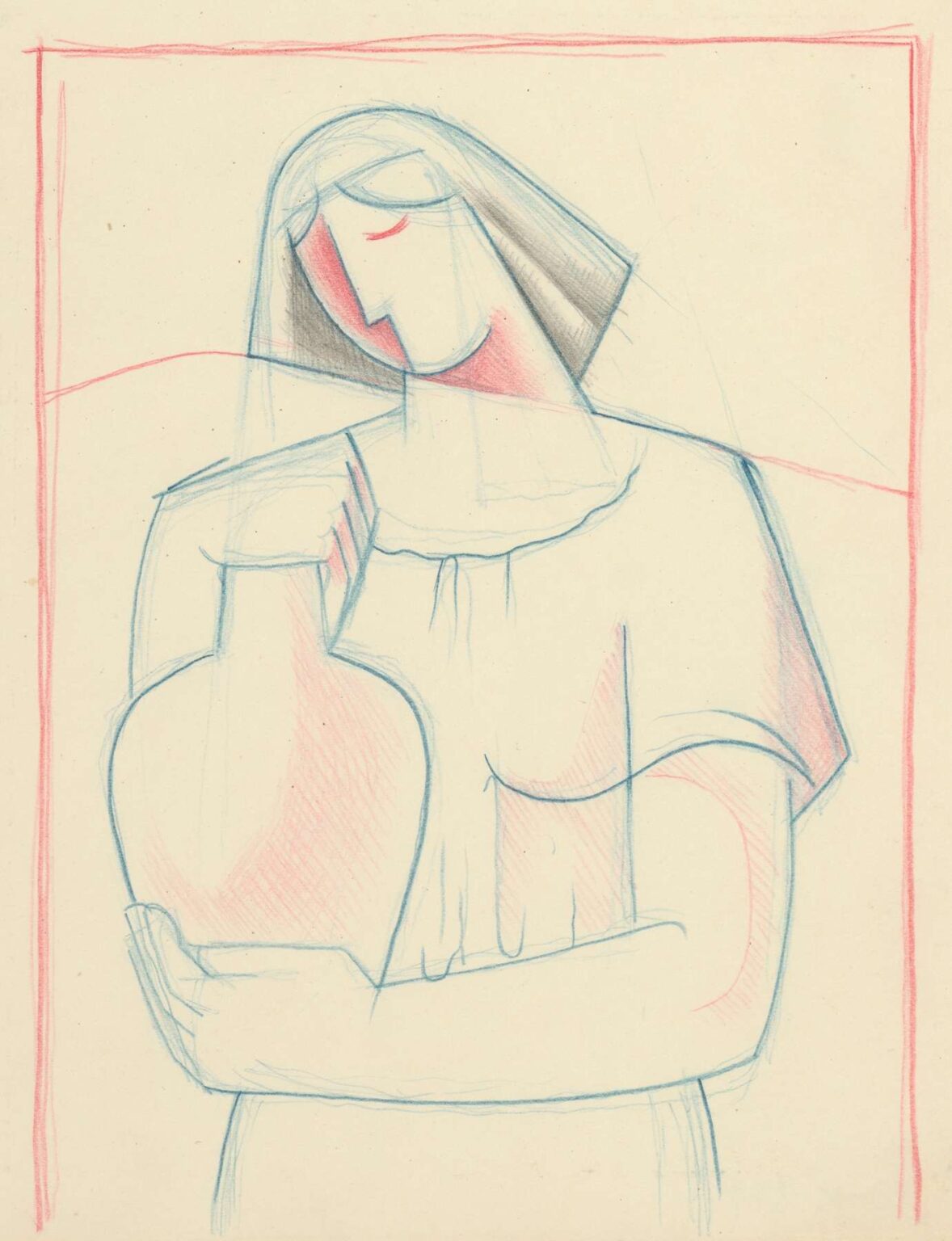

In Girl with a Jug (1938), Mikuláš Galanda presents a lyrical vision of feminine serenity, using the spare economy of line and subtle tonal accents to convey both physical presence and internal poise. At first glance, the drawing’s gentle contours and soft shading draw the viewer into an intimate encounter with a young woman cradling a simple vessel. The image feels simultaneously timeless and modern, evoking ancient motifs of the maid and the amphora while embracing the flatness and abstraction prized by early twentieth‑century avant‑garde movements. Through a careful orchestration of form, space, and gesture, Galanda transforms a humble domestic object—the jug—into a potent symbol of sustenance, ritual, and quiet grace. This analysis will examine the work’s historical roots, formal structure, symbolic resonances, and enduring impact, revealing how Galanda’s mastery of graphic art elevates a minimalist composition into an eloquent meditation on femininity and daily life.

Historical and Cultural Context

The late 1930s in Czechoslovakia were marked by social flux and growing political anxiety, as the republic confronted external threats and internal debates over national identity. Artists responded by seeking modes of expression that could communicate universal human experiences without descending into overt propaganda or escapist fantasy. Mikuláš Galanda, a proponent of Slovak modernism, navigated these currents by blending folk traditions with the formal innovations of European avant‑garde. Having co‑founded the Nová Trasa (New Path) group a decade earlier, Galanda championed clarity of design, accessibility, and a solidarity with working‑class subjects. In Girl with a Jug, created as geopolitical tensions mounted, he retreats to a scene of everyday ritual—drawing water, pouring liquid, or preparing a meal—to affirm the sustaining power of ordinary gestures. The work thus situates itself at the intersection of personal introspection and collective resilience, offering solace in the continuity of humble, life‑affirming tasks.

Mikuláš Galanda’s Artistic Evolution

Born in 1895 and trained at the Budapest Academy, Galanda absorbed academic traditions before embarking on a journey through Munich, Vienna, and Paris, where he encountered Secessionism, Cubism, and Expressionism. By the mid‑1920s, he had turned from easel painting to graphic techniques—woodcut, lithography, and pen‑and‑ink drawing—finding in them a means to distill subjects into their essential shapes. His early folk‑inspired prints featured decorative patterns and narrative scenes, but over time his style became increasingly reductive, emphasizing pure contour and minimal shading. Girl with a Jug represents a peak of this late‑period refinement, in which a handful of lines and tone washes suffice to evoke three‑dimensional form and emotional depth. Galanda’s evolution reflects a broader modernist quest: to strip away excess and expose the core of human experience, rendered in a visual language at once direct and evocative.

Formal Elements: Line and Contour

Line reigns supreme in Girl with a Jug. Bold, unbroken strokes outline the figure’s profile, shoulders, and arms, establishing a seamless silhouette that flows around the vessel. The line work exhibits calligraphic discipline: thick contours anchor the composition, while thinner internal lines delineate facial features, the drip of fabric, and the rim of the jug. Each mark appears confident and unhesitating, yet alive with subtle variation in pressure and rhythm. This sensitivity to line weight generates a sense of volume without resorting to intricate modeling. The hair, rendered with parallel hatch‑like strokes, contrasts with the smooth expanses of skin and fabric, providing textural variety. Through masterful contour, Galanda animates a still scene, suggesting weight, gravity, and the gentle tension of muscle under skin.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Galanda composes Girl with a Jug within a rectangular border that frames the subject close to the picture plane, fostering intimacy. The figure is slightly off‑center, her head tilting toward the vessel and creating a dynamic diagonal axis. Her arms form two gentle curves that cradle the jug, their intersection drawing the eye to the object’s voluminous form. Negative space around the figure—particularly between the jug and the woman’s torso—allows the viewer’s gaze to circulate freely, emphasizing the interplay of presence and void. The minimal background ensures absolute focus on the woman and her action, while the framing lines serve as a subtle echo of the jug’s rim, reinforcing unity. The overall balance between simplicity and movement animates the composition, making it feel both stable and alive.

Color, Tone, and Shading

Though executed on cream-toned paper, the drawing utilizes two colored media—blue pencil and red chalk—to articulate structure and shadow. The blue pencil traces the primary outlines, lending a crisp, architectural quality to the form. Red chalk provides soft accents on the cheeks, neck, and the jug’s surface, suggesting warmth and the play of light on curved planes. Black charcoal or graphite appears layered in the hair and along the jug’s rim, anchoring the composition with dark anchors. This triadic palette remains subdued, yet achieves a rich tonal harmony, where cool and warm tones balance each other. The shading is applied sparingly—light hatching in the folds of fabric and under the arm—allowing the drawing to breathe. The selective tonal variation communicates depth and roundness without overwhelming the purity of the line.

The Jug as Symbolic Center

At the heart of the composition lies the jug, a vessel both functional and symbolic. In art history, containers often represent abundance, hospitality, or the feminine principle of nurturing. Galanda’s jug, rendered with just enough detail to suggest earthenware form, becomes an extension of the woman’s self—something she both holds and offers. The gesture of cradling the vessel evokes notions of care, protection, and the cyclical nature of nourishment. The jug’s rounded shape contrasts with the angular planes of the figure’s shoulders and neck, creating a visual dialogue between rigidity and softness. By positioning the jug at the crossing of two arm curves, Galanda underscores its centrality: it is not merely an accessory but a focal point around which the woman’s identity and action revolve.

Gesture and Emotional Resonance

The mood of Girl with a Jug is one of contemplative calm. The woman’s head is slightly bowed, her eyes closed or downcast, suggesting inward focus. Her lips, drawn with a single curved line, carry a hint of serenity. The arms, neither stiff nor slack, convey gentle strength—a readiness to support the vessel without tension. This poised equilibrium translates into an emotional tenor that feels meditative rather than dramatic. The viewer senses a quiet reverence for the act of holding something dear, as though the simple gesture bears profound human significance. Galanda’s restraint—eschewing dramatic postures or expressive flairs—invites the audience to discover tranquility in everyday rituals, highlighting the dignity of simple tasks.

Relation to Slovak Modernism

Girl with a Jug embodies the ethos of Slovak modernism’s search for a national art that reconciled tradition and innovation. Galanda drew upon folk motifs and peasant life, but interpreted them through the lens of European abstraction and graphic clarity. His approach contrasted with more theatrical expressionism, favoring instead directness and accessibility. The figural simplicity echoes Slovak woodcuts and embroidery patterns, while the flatness and compositional economy resonate with Czech Cubism and German New Objectivity. In this fusion, Galanda crafted a visual language that spoke both to local audiences familiar with folk imagery and to international viewers attuned to modernist aesthetics. The result is a work that participates in a broader avant‑garde dialogue without abandoning its cultural roots.

Technical Mastery and Medium

Galanda’s facility with mixed drawing media becomes apparent in Girl with a Jug. The interplay of pencil, chalk, and possibly charcoal reflects a deep understanding of each material’s expressive potential. Pencil allows precision in contour, chalk lends softness in flesh tones, and charcoal imbues depth in darker zones. The seamless transitions between these media speak to a practiced hand; there is no visible hesitation or disjunction. The paper’s warm ground interacts subtly with the applied colors, providing a cohesive backdrop that unifies the elements. Galanda’s technique balances spontaneity—seen in the fluid linework—with careful planning, evident in the compositional harmony. This combination of free gesture and measured structure showcases the artist’s technical maturity and his commitment to drawing as a primary art form.

Symbolic Reading of Femininity and Ritual

Beyond its formal virtues, Girl with a Jug invites symbolic interpretations of the feminine role and ritual practice. The woman’s gentle embrace of the vessel suggests themes of maternity, offering, and the sacredness of domestic labor. In many cultures, the act of fetching or carrying water has ritualistic connotations: a moment of pause, reflection, and connection to natural cycles. Galanda abstracts these cultural overtones into a universal image, one that transcends specific geography yet resonates with the archetype of the Life‑Bearer. The absence of a detailed setting removes temporal markers, underscoring the timelessness of the scene. The drawing thus functions on multiple levels: as a portrait of a singular figure, as an emblem of feminine strength, and as a modernist meditation on ritual gesture.

Legacy and Continuing Influence

More than eight decades after its creation, Girl with a Jug remains a touchstone in studies of European graphic art. Its elegant economy of means has influenced generations of illustrators and designers who seek clarity and emotional resonance through minimal form. Exhibitions of Central European interwar art frequently feature this drawing as exemplary of how artists responded to social uncertainty by reaffirming simple human values. Contemporary practitioners cite Galanda’s work for its capacity to merge folk inspiration with avant‐garde principles, inspiring projects in branding, editorial illustration, and fine art. The drawing’s universal appeal lies in its ability to evoke introspection and empathy without fixating on historical specifics, securing its place among the enduring images of twentieth‐century modernism.

Conclusion

Girl with a Jug exemplifies Mikuláš Galanda’s talent for translating everyday rituals into eloquent visual poetry. Through a harmonious blend of line, tone, and composition, Galanda elevates a humble domestic scene into a meditation on femininity, care, and the sustaining power of simple gestures. The drawing’s minimalist aesthetic and symbolic depth reflect both the cultural tensions of 1930s Czechoslovakia and the timeless quest for human connection. As a masterpiece of Slovak modernism, it continues to inspire, reminding viewers that even the most ordinary acts can possess profound beauty and meaning when rendered with clarity and compassion.