Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Nice-Period Studio

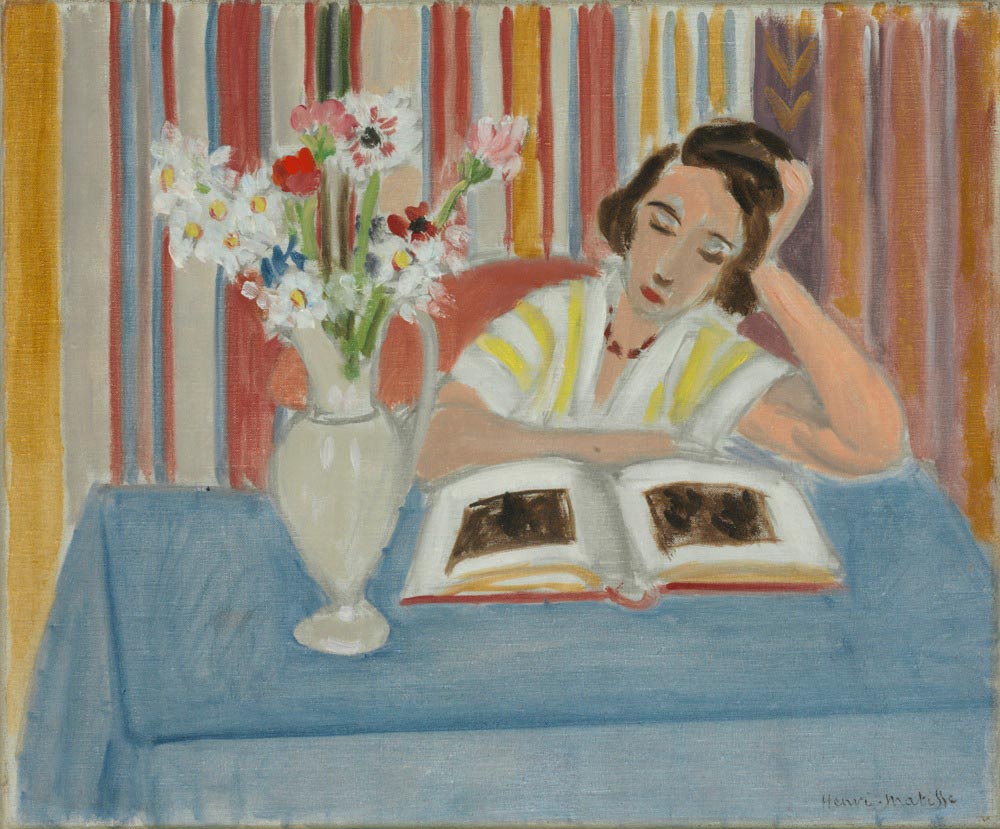

Henri Matisse painted “Girl Reading, Vase of Flowers” in 1922, deep in his Nice period, when quiet interiors became laboratories for calibrating color, light, and human presence. After the upheavals of the 1910s, he sought clarity rather than clamor, preferring rooms where a window, a patterned textile, a bouquet, and a single figure could be tuned like instruments. In this painting the studio is modest—a striped hanging for a backdrop, a blue-clothed table, a pale ceramic vase, and a young woman absorbed in a book. No grand narrative intrudes. Instead, the theme is the practice of attention: how reading, flowers, and color harmonize to form a complete climate of thought and rest.

Composition As A Calm Triangle

The composition forms a stable triangle whose points are the bouquet, the reader’s head, and the open book. The table is a broad, horizontal plane that anchors the lower half of the canvas. Above it, the figure leans inward from the right, her head propped by a bent arm; the vase rises from the left edge to balance her weight. Between them, the open book lies like a small stage—a bright hinge that connects the two vertical masses and leads the eye into the center. Behind everything hangs the striped curtain, whose vertical rhythm keeps the whole arrangement breathing while preventing the scene from floating. Matisse’s orchestration is exact: the figure’s downward gaze points toward the book; the bouquet’s stems lean slightly inward, echoing that glance; and the stripes converge just enough to draw attention to the reader’s face.

The Table As A Plane Of Thought

Matisse often treats tables as pictorial platforms. Here, the blue tablecloth is not mere furnishing; it is a plane of thought on which reading occurs. Its color is a measured, gray-leaning blue that cools the warm lights of the skin and the bouquet, a tone chosen to steady the mood. The cloth’s brushwork is soft and even, with just enough variation to suggest woven texture. Because the table occupies nearly half the picture, it acts as a calm sea that makes the smaller, livelier forms—the turning pages, the flowers—stand out in relief. The edge of the cloth, subtly indicated by a shadowed fold, creates a horizontal bar that rests the eye before it moves upward again.

The Reader’s Pose And The Ethics Of Attention

The girl’s posture is a study in unforced concentration. Her head tips toward the page; one forearm lies along the table; the other hand cradles the temple, a gesture that slows time without theatricality. Matisse refuses the clichés of drama—no emphatic facial features, no exaggerated tilt. Instead, he uses economy. The mouth is a single, quiet note; the eyelids are two soft arcs; the hair is brushed into dark planes that frame the face. The result is an image of reading that feels genuinely lived: the body arranges itself naturally in service of attention. This ethic—attention as care, not performance—pervades the Nice interiors and reaches a distilled clarity here.

Color Chords And The Temperature Of Calm

The palette is organized into three interlocking chords. The first is the cool blue of the table, repeated more lightly in the curtain’s bluish stripes. The second is the warm group of creams, apricots, and rose that defines the skin, the book’s edge, and some of the floral notes. The third is the vegetal green of stems and foliage, which bridges cool and warm like an intermediary register. Matisse avoids harsh complements. Instead, he lets neighbors modulate one another: a gray-blue next to a warm white, a pale yellow beside a muted red, a soft olive next to a lavender stripe. This adjacency creates atmosphere—neither sugary nor severe—precisely suited to the painting’s theme of sustained, quiet focus.

The Striped Backdrop As Pictorial Metronome

The vertical stripes behind the sitter are not wallpaper in the descriptive sense; they are a metronome that regulates the picture. Alternating bands of mustard, rose, cream, lavender, and blue set a steady beat that holds the eye upright while the figure leans. At the far right, Matisse interrupts the stripes with a simple chevron motif, a small flourish that prevents repetition from becoming mechanical. The stripes also calibrate depth with remarkable economy: because their color and saturation vary slightly from left to right, they push some areas back and pull others forward, so the figure feels seated in a shallow but breathable space.

The Bouquet As Lyrical Counterpart

Opposite the reader, the bouquet blooms like a lyric phrase. Daisies, carnations, and small garden flowers gather in a pale ceramic vase whose shape echoes the arc of the reader’s bent arm. Matisse paints petals as quick touches—opaque whites, pinks, and a sudden red—allowing stem greens to peek through so the cluster feels airy rather than dense. The bouquet’s white highlights, placed sparingly along the vase and some petals, introduce the highest values in the composition, lifting the left side of the canvas and reflecting a soft light back toward the book. The flowers are not there to symbolize; they are present to balance, to breathe, and to articulate the room’s air.

The Open Book As A Quiet Stage

The open book is a small theater of rectangles: two creamy pages with darker images centered on each side, a red binding that glows where the page turns, and a pale seam down the fold. Matisse paints the book with a clarity that stops short of pedantry. The images are indicated as dark plates rather than described, keeping attention on the act of reading rather than on what is read. The red binding deserves notice. It repeats, in miniature, the warmer reds of the curtain and the flowers, threading a chromatic line from background to object to figure. The book thus becomes a hinge not only for composition but also for color.

Brushwork And The Pulse Of The Room

The paint handling is brisk and articulate. Across the tablecloth, strokes flow horizontally, agreeing with the plane’s breadth. On the stripes, they run vertically, reinforcing the wall’s rise. The figure’s skin is built from soft, short strokes that turn gently at cheek and forearm, shifting temperature rather than value to declare volume. Petals are single dabs, leaves are linear flicks, and the vase is laid with a few rounded sweeps that thicken at the shoulder. Nothing is labored; everything is tuned to a speed that feels like daylight—decisive but unhurried. This rhythm of touch is how Matisse keeps the painting’s quiet from becoming stasis.

Light As A Continuous Envelope

The illumination is even and coastal, as if entering from an unseen window to the left. Shadows are colored, not black—the underside of the arm cools toward gray-violet, the vase darkens into a milky celadon, the book’s plates sink into warm brown. Highlights are modest and functional: a glint on the vase, a soft flare along the page edge, a lighter note on the cheek. Because light is a continuous envelope rather than a spotlight, color carries the emotion. The room glows softly, the way rooms do in Nice when afternoon sun filters through curtains.

Drawing Inside Color And The Intelligence Of Omission

Matisse’s drawing is carried by color boundaries and a few calligraphic accents. The hand near the temple is a simple loop with two or three interior strokes hinting at fingers; the elbow is an elastic curve that swells where bone meets flesh; the necklace is a short chain of red notes that ties head to torso. The curtain’s stripes are straight enough to read as fabric but soft enough to breathe. By omitting fussy detail, Matisse keeps attention on the significant relations: head to page, bouquet to reader, table to backdrop. The omissions are not absences; they are invitations for the viewer to complete the scene through looking.

Pattern And Plain In Equilibrium

A central pleasure of the painting is the balance between pattern and plain. The curtain is highly patterned; the tablecloth is nearly uniform. The bouquet is a concentrated scatter; the book is rectilinear calm. The dress provides a middle term—white ground with soft yellow stripes across the shoulders—so the figure belongs to both worlds. This equilibrium allows the room to feel full but not busy, intimate but not confined. It is the architectural logic of the Nice period in miniature: decorate the planes that can support rhythm, keep the others serene, and let a few accents carry the melody.

The Psychology Of Reading

Although the sitter’s face is simplified, the psychology of reading is palpable. The lowered eyelids, the weight of the head on the hand, and the slight forward fall of the shoulders model a mind turned inward. Yet the scene is not sealed off. The bouquet’s freshness and the curtain’s bright stripes keep the room communicative, as if the world outside the page continues to hum gently. Matisse suggests that the act of reading is a negotiation between inner and outer attention—an ideal theme for an artist dedicated to harmonizing forms and feelings.

Space Built By Overlap And Tonal Steps

Depth is achieved without linear perspective. The tabletop overlaps the figure’s forearms; the book overlaps the table; the vase overlaps the curtain; and the stripes recede by tonal softening rather than by measurable diminution. These overlaps are small but decisive, creating a shallow space that keeps all elements present. Because the space is tight, relationships become more legible: the book sits close enough to feel held; the vase feels within arm’s reach; the backdrop feels like fabric, not architecture. In this scale, intimacy replaces spectacle.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

Repetition organizes the painting like music. Vertical stripes repeat in varied colors; horizontal table strokes repeat in modulated blues; round flower heads repeat as scattered notes; red returns in the necklace, book edge, and a carnation. The eye follows a consistent path—up the vase, across the bouquet, down to the book, over to the reader’s face and shoulder, and back to the table’s edge—before beginning again. Each lap yields a new inflection: a cooler blue in the cloth, a warmer rose in the petal, a subtler shadow along the wrist. The picture thus offers not an instant message but a sustained melody.

Material Presence And Tactile Cues

Though the image is airy, tactile cues abound. The vase’s glaze is suggested by milky highlights that slide along its curve; the tablecloth reveals its woven nature in the way paint drags over canvas tooth; the paper pages are matte, absorbing light differently than the glossy ceramic; the flowers thicken into small ridges where pigment is dabbed more generously. These material signals keep the room grounded in bodily memory: the feel of turning a page, the cool weight of a jug, the brush of petals near the face.

Relationship To Other Nice Interiors

“Girl Reading, Vase of Flowers” converses with many interiors from 1920–1923 in which a model sits near a bouquet at a small table. Compared with more crowded odalisque scenes, this canvas is pared and lucid: a single textile, a single vase, a single activity. It shares with “Interior in Nice, a Siesta” the theme of restoration, and with “Confidence” the quiet dignity of companionship—here, the sitter’s companion is a book. The painting forecasts later Matisse, too: the bold vertical backdrop anticipates the simplified, banner-like structures of the 1930s and the ultimate reduction of motif in the cut-outs.

Why The Painting Still Feels Modern

The work endures because it models a sustainable image of everyday life. It proposes that one can build a complete world from tuned planes, a few objects, and a human gesture of attention. No narrative is demanded; no symbolism is forced. Instead, color and relation do the work. In a culture saturated with visual noise, this room’s measured chord—blue table, striped wall, pale vase, quiet reader—feels newly generous. It shows how a painting can cradle a daily practice, like reading, and make it resonant without inflating it.

Conclusion: Reading, Flowers, And A Room That Breathes

“Girl Reading, Vase of Flowers” distills Matisse’s Nice-period aims into a lucid scene. A triangular composition of bouquet, head, and book anchors the eye; a stripe-filled backdrop keeps rhythm; a blue table steadies the mood; and a pared vocabulary of color and line turns attention itself into subject. The painting is a classroom in how to look at ordinary life with care. Its promise is not spectacle but depth: if you linger, the room continues to offer air, light, and a humane tempo in which the mind can both read and rest.