Image source: artvee.com

Historical and Biographical Context

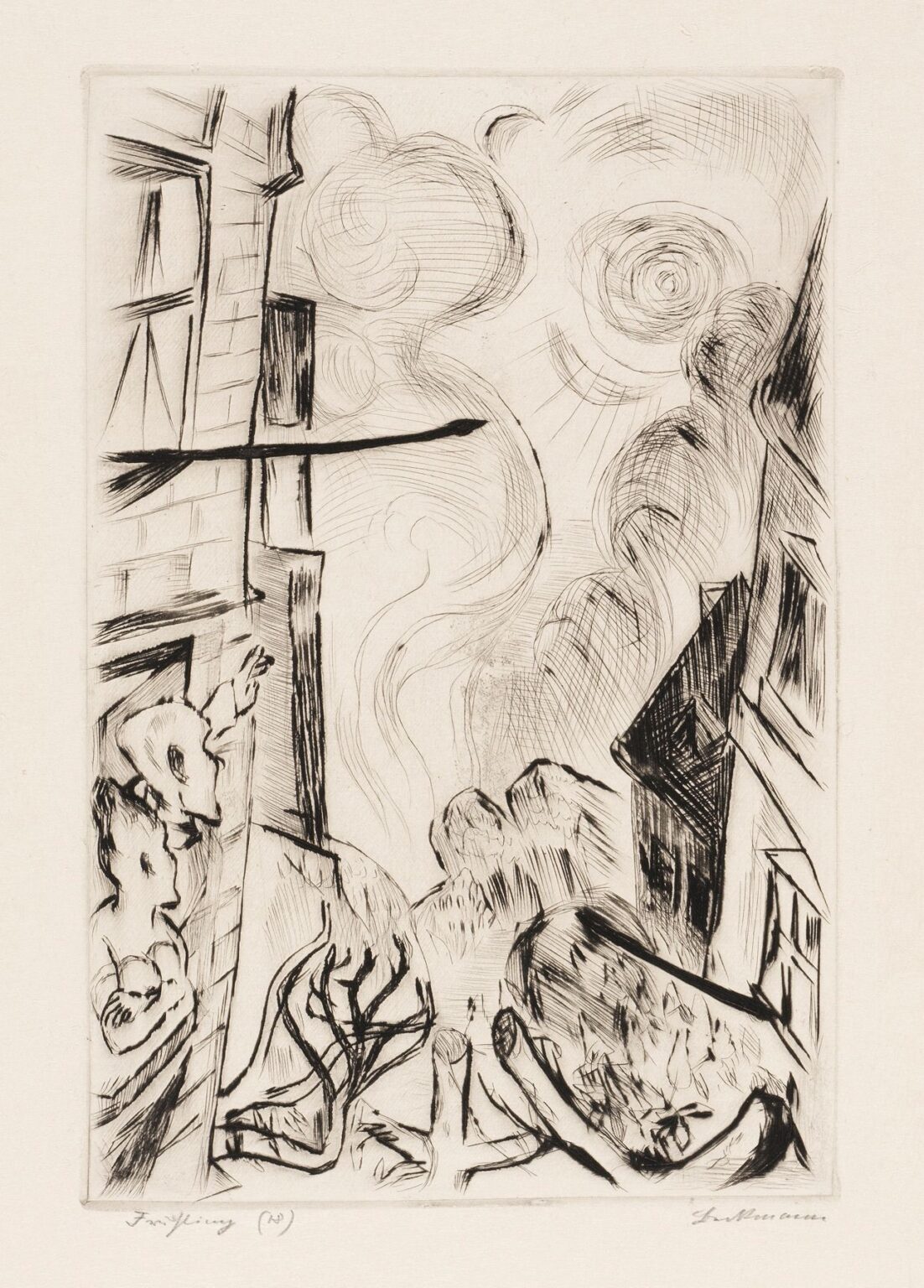

Max Beckmann created Gesichter Pl. 17 between 1914 and 1918, during the cataclysm of the First World War. Drafted into military service in 1915, Beckmann witnessed the horrors of trench warfare and the collapse of European society. Discharged due to illness, he returned to Berlin with a shattered faith in progress and civilization. Rather than retreating into comfort, he turned to printmaking—etching and drypoint—as an urgent means to confront collective trauma. His Gesichter (“Faces”) series, of which Pl. 17 is a pivotal plate, abandons formal portraiture in favor of psychological landscapes composed of faces, bodies, and symbolic motifs. These works distill the dislocation and existential dread of wartime Europe into sharply etched signs and fragmented narratives.

Technique and Materiality

Beckmann’s approach to Gesichter Pl. 17 combines hard‑ground etching with vigorous drypoint burr. After covering a copper plate with a waxy ground, he meticulously incised lines that an acid bath would bite into. The hard‑ground lines remain precise and clear, mapping out the ladder, building facades, and geometric forms. He then added drypoint—directly scratching into the plate without ground—to generate burr around key elements such as the swirling clouds and contorted limbs. This burr holds extra ink, yielding velvety dark tones that contrast with the crisp etched lines. The result is a dynamic interplay between sharp delineation and soft tonality. Beckmann’s inking and wiping were equally decisive: he retained ink in the burr‑laden zones while nearly scouring flat areas clean, amplifying the drama of light and shadow.

Fractured Space and Perspective

One of Gesichter Pl. 17’s most striking features is its refusal of a single, unified perspective. On the right side, building facades tilt at impossible angles, their frames and windows rendered in precise, architectural hatchings. These geometric fragments suggest bomb‑shattered city blocks or the unstable foundations of prewar order. On the left, two hooded figures lean out of a shuttered window, their forms emerging from darkness. Between these poles, the ground plane dissolves: fragmented legs and arms appear in midair, neither wholly connected to bodies nor fully distinct. The central ladder, rendered in sharp diagonal lines, anchors the scene yet seems to vanish into a vortex above. Beckmann orchestrates these dislocations to evoke the shattering of space and self under the weight of mass violence.

Symbolism of the Ladder

Throughout his work, Beckmann returned to the ladder as a potent symbol of ascent, escape, and spiritual aspiration. In Pl. 17, the ladder stands at the nexus of the composition—a vertical axis cutting through horizontal chaos. Its rungs grow fainter as they rise, as if dissolving into the swirling sky. This ladder no longer promises solid ground or celestial ascent; instead it conveys the impossibility of transcendence when society crumbles. The ladder’s brittle etching echoes the vulnerability of individual lives in wartime, and its broken continuity mirrors the fractured psyches Beckmann sought to portray.

The Masked and Hooded Figures

In the left margin, Beckmann places two figures shrouded in hooded garments. Their faces read like masks—featureless or hollowed—which underscores themes of anonymity and dehumanization. These hooded forms reach outward, their hand gestures oscillating between pleas for help and warnings of impending danger. The masks may allude to the roles soldiers and civilians were forced into: victims, witnesses, aggressors. By reducing faces to generic visages, Beckmann comments on the erasure of personal identity within the machinery of war. Their placement in darkness also suggests the unseen toll of conflict—the psychological scars beneath the surface.

Disembodied Limbs and Human Fragmentation

Across the plate, Beckmann depicts arms and legs as fragmented elements drifting in space. A sinewy arm wraps around an unseen body; a spindly leg appears mid‑stride without torso or foot. These disembodied limbs evoke the physical and moral dismemberment wrought by total war. The cross‑hatchings around joints intensify a sense of strain and distortion. Beckmann’s technique here is visceral: the drypoint burr creates an almost sculptural quality in the limbs’ shading, lending them a haunted presence. The fragmentation of the human form stands as a stark metaphor for shattered societies and broken individuals.

Swirling Skies and Cosmic Turmoil

Hovering above the terrestrial fractures, Beckmann etches patterns of swirling clouds and concentric circles. These curves—lighter and more gestural than the architectural lines below—conjure both halos and storm vortices. The sky in Pl. 17 is not an indifferent backdrop; it is an active force, bearing witness to the agony on earth. The spirals recall medieval depictions of holy light, yet here they twist with turbulence. This sky‑scape suggests that war’s chaos extends to the cosmos itself, unsettling myths of divine order. Beckmann’s sky thus unites heaven and earth in a shared upheaval.

Tension Between Line and Void

Beckmann’s etching balances densely worked passages against vast empty spaces. Under the ladder and around the building frames, heavy hatching produces deep shadow. By contrast, the lower‑right quadrant features large expanses of nearly unetched paper. These voids function as visual silences, intensifying the emotional dissonance. The eye moves from solid ink clusters to blank paper, experiencing a jarring rhythm of presence and absence. This technique mirrors the experience of trauma—moments of unbearable intensity punctuated by numb emptiness.

Moral and Psychological Dimensions

Gesichter Pl. 17 operates on both moral and psychological registers. Beckmann does not depict a literal battle scene; instead, he creates a moral tableau of suffering and indifference. The hooded figures, the fractured bodies, the empty ladder—all point to a world where compassion and coherence have been ruptured. At the same time, the work maps inner territories of fear, alienation, and the struggle to find meaning amid devastation. Beckmann, drawing on Expressionist currents, externalizes inner turmoil through external form, yet his work remains anchored in symbolic order rather than pure abstraction.

Relation to Beckmann’s Broader Oeuvre

While grouped with German Expressionists for his emotional intensity, Beckmann’s concerns consistently moved toward narrative and allegory. His postwar masterpieces—Departure, Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery—elaborate themes first sketched in the Gesichter plates. In Pl. 17, Beckmann tests the limits of printmaking, setting the stage for his later large‑scale paintings. The formal innovations—layered perspectives, symbolic ladders, fractured figures—would reappear in his oeuvre as he grappled with exile, Nazism, and ultimately New York exile.

Reception and Legacy

Early audiences found the Gesichter series unsettling; its fractured forms resisted easy readings. Yet by mid‑century, critics recognized Beckmann as a pivotal figure in modern art. Pl. 17 in particular has been cited in studies of war art for its directness and complexity. Contemporary printmakers and artists continue to draw inspiration from Beckmann’s fearless synthesis of technique and message. In exhibitions, Pl. 17 is often shown alongside other war‑time etchings to illustrate how print media can bear witness to historical trauma.

Conservation and Print States

Beckmann’s Gesichter Pl. 17 exists in multiple states. Early impressions, pulled immediately after burr creation, display richer tonal depth and velvety blacks. Later states, as the burr wore down, reveal crisper lines but less tonal contrast. Museums guard these impressions against light and humidity to preserve fragile burr burrs. Scholarly catalogues raisonnés document minute variations between states, allowing curators to trace Beckmann’s refining process.

Conclusion

Max Beckmann’s Gesichter Pl. 17 transcends its medium by transforming a copper plate into a mirror of collective anguish. Through fractured perspectives, disembodied limbs, hooded figures, and a vanishing ladder, Beckmann captures the disintegration of war‑torn Europe. His masterful interplay of etching and drypoint burr yields an etching that is at once razor‑sharp and hauntingly soft. Over a century after its creation, Pl. 17 remains a profound meditation on the human cost of conflict and the search for meaning amid ruin.