Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

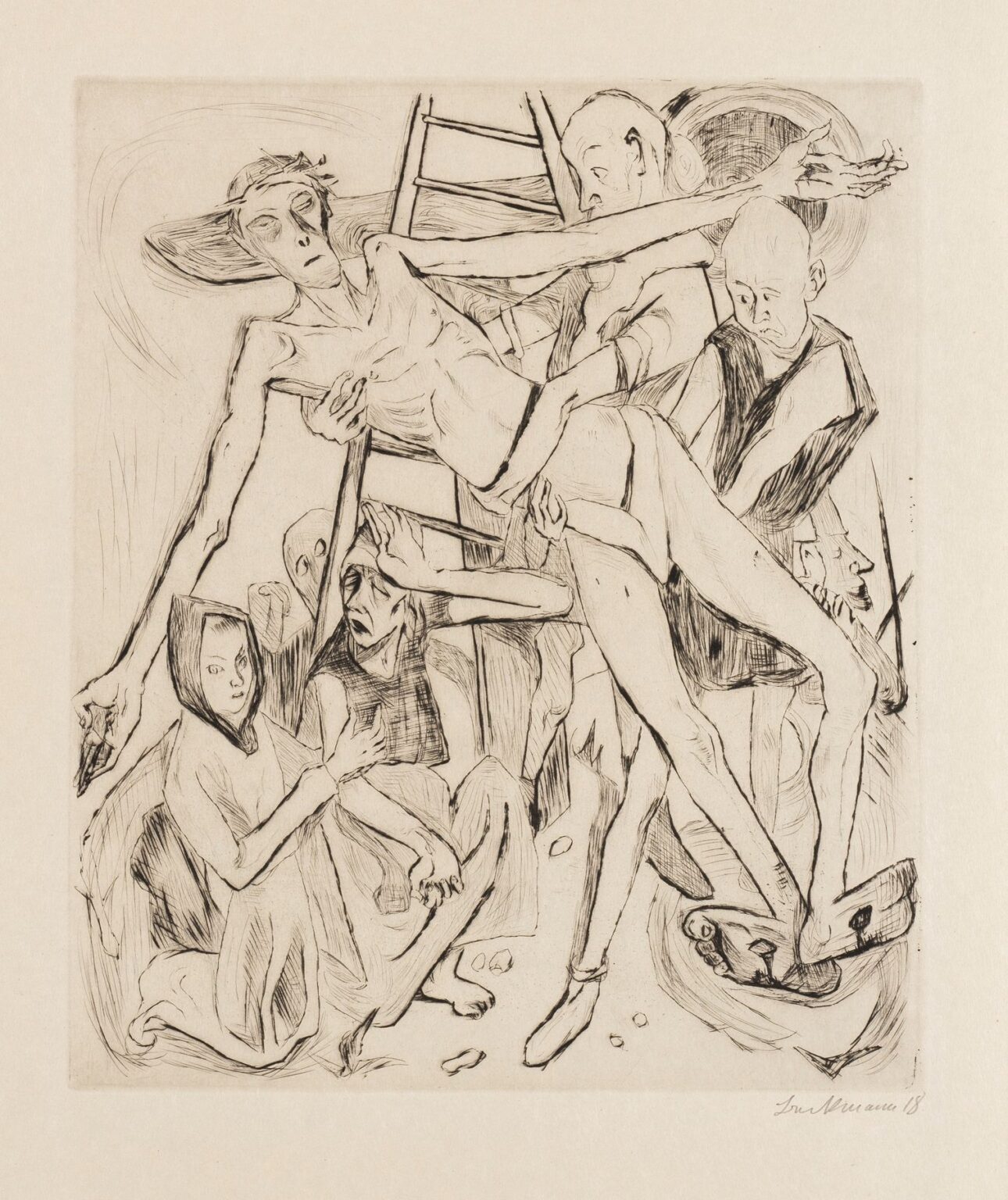

Max Beckmann’s Gesichter Pl. 16 (Faces Plate 16), etched between 1914 and 1918, stands as one of the most harrowing and dynamic entries in his celebrated Gesichter series. Created amid the cataclysm of World War I, this etching abandons traditional portraiture in favor of a frenetic montage that confronts viewers with a raw vision of human suffering, dislocation, and spiritual questioning. In Pl. 16, Beckmann deploys an intricate web of lines and forms—twisting bodies, masking figures, angular ladders, and anguished gestures—so that the plate becomes both a document of collective trauma and an allegory of the soul’s struggle. This analysis will unpack the historical context of the work, Beckmann’s technical mastery in etching and drypoint, the composition’s shifting spatial logic, the interplay of gesture and expression, recurring symbolic motifs, and the plate’s enduring resonance in art history.

Historical and Biographical Context

Between 1914 and 1918, Europe reeled under the unprecedented devastation of the Great War. Beckmann, drafted into the German army in 1915 but later invalided out, returned to Berlin suffering from physical illness and psychological shock. The explosion of modern weaponry, the collapse of old certainties, and the resulting social upheaval propelled him away from his prewar academic painting style toward graphic work that could more immediately capture the turbulence of his times. The Gesichter cycle—an ambitious series of over twenty etchings—became Beckmann’s primary vehicle for processing wartime horror. Unlike commissioned battle scenes or heroic propaganda, his plates present intimate, often claustrophobic visions that focus on the human face and body as sites of trauma, identity crisis, and spiritual confrontation.

Technique: Etching, Drypoint, and the Language of Line

Beckmann executed Pl. 16 on a copper plate using hard‑ground etching combined with drypoint, a combination that yields both razor‑sharp contours and velvety textural burr. His process began with hard‑ground etching: drawing the composition with needle on a wax‑resist layer, then bathing the plate in acid. Multiple acid immersions—short for delicate lines around facial features, longer for deeper structural lines in bodies and ladders—allowed him to calibrate line weight. After wiping the ground, he introduced drypoint burr—scratched directly into the metal—for areas of heightened emotional intensity: the edges of outstretched arms, the rims of collapsing bodies, the halo around the central cruciform figure. The burr catches extra ink, producing soft, glowing lines that contrast with etched strokes. The final print, pulled on dampened cream wove paper, reveals Beckmann’s virtuosity: a dense network of hatchings, cross‑hatchings, and burr lines that animate the plate with restless energy.

Composition: A Cradle of Bodies and Ladders

Unlike a conventional portrait, Pl. 16 unfolds as a layered montage, subdivided neither by frames nor by hierarchical zones. At center, a thin, Christ‑like figure—crowned, perhaps ironically, with thorns—hangs limply across a broken ladder. Its arms stretch wide, forming an almost cruciform posture. On the right, two figures—one balding and introspective, the other turned away—support the central body, their elongated limbs wrapping around the crosspiece. At bottom left, a seated figure shields its face, while tendrils of line suggest a kneeling companion offering solace. In the background, swirling clouds and half‑hidden figures merge with the ladder’s remnants, creating a sense of environment rather than empty space. The ladder itself, a recurring motif in Beckmann’s oeuvre, here stands broken, its rungs fragmented, suggesting failed ascents, disrupted journeys, or the collapse of spiritual or social structures.

Spatial Dynamics and Psychological Dislocation

Beckmann rejects Renaissance perspective in Pl. 16, preferring a fragmented, collapsing space that mirrors psychological dislocation. The ladder slopes at an awkward angle, intersecting with receding hatches that imply floorboards or beams, but these vanish as the eye travels across the plate. Figures recede or advance unpredictably: the kneeling figure at left seems closer to the viewer than the standing braced figure on the right, even though they share the same horizontal register. This deliberate spatial confusion enhances the sense of alienation and crisis; no stable ground exists, no single viewpoint offers refuge. The viewer, too, becomes unmoored, compelled to navigate a shifting labyrinth of bodies and gestures.

Gesture and Expression: Silent Drama

Each figure in Pl. 16 conveys a distinct emotional tone through posture and gesture. The central figure’s limp body, head tilted back, eyes closed, evokes martyrdom, sacrifice, or utter exhaustion. The supporting figures’ extended arms—one reaching out, the other withdrawing—speak to conflicting impulses of care and self‑preservation. The kneeling pair at bottom left communicate horror and compassion: one covers its face with both hands, while the other, slightly behind, extends an arm in a gesture of offering. Beckmann’s etched lines around hands—short, staccato hatchings—accentuate the tension in fingers and knuckles. Across the plate, bodies arch, twist, and lean, creating a silent choreography of despair and solidarity.

Symbolic Motifs: Ladder, Crown, and Fragmentation

Beckmann embeds potent symbolic imagery within Pl. 16. The ladder often signifies aspiration or divine ascent; here, its broken state suggests thwarted hopes or the collapse of religious and moral certainties. Placing the central figure across its rungs invokes crucifixion, martyrdom, or a world turned upside down. The thorn‑like crown atop the head resonates with Christ‑iconography but may also signify collective suffering inflicted by human cruelty. Fragmented limbs and overlapping forms convey dismemberment—both physical and moral—as if humanity itself has been torn apart. Yet, the presence of supporting figures and offered hands hints at resilience and human connection even in catastrophe.

Tonal Contrast: Light, Shadow, and the Burr Glow

Beckmann exploits etching’s full tonal range. Deep cross‑hatched areas under the ladder and around the supporting figures anchor the plate in shadow, while unetched regions—such as portions of the central body and the top‑left background—allow the paper’s pale tone to shine through as highlight. Drypoint burr lends a glow around faces, hands, and the broken ladder, producing halos of light that suggest spiritual or emotional intensity. This chiaroscuro effect is not naturalistic but expressive: stark contrasts amplify the drama of each gesture and heighten the overall atmosphere of tension.

Relation to Beckmann’s Wartime Work

Gesichter Pl. 16 epitomizes Beckmann’s wartime pivot from studio painting to socially engaged printmaking. Whereas his prewar canvases often depicted tranquil interiors or portraits, the Gesichter series—especially plates 15 through 18—embraces raw emotion, collective trauma, and allegorical density. In later paintings like The Night (1918–19), Beckmann would revisit similar themes on a grand scale, staging crowded, nightmarish scenes of violence and abandonment. Pl. 16, however, distills these concerns into an intimate yet expansive plate, demonstrating how the etching medium allowed for rapid, direct responses to unfolding historical crises.

Edition, Printing, and Conservation

Beckmann supervised a small edition of Pl. 16, ensuring that the first‑state impressions captured the full burr luminosity and deep acid‑etched lines. Early impressions, printed on fine laid paper, exhibit pronounced drypoint burr around the central figure’s head and shoulders. Later pulls, taken after plate wear set in, lose some of this burr glow but retain the etched contours. Conservators today house Pl. 16 impressions in controlled light and humidity, matting them with acid‑free board to prevent discoloration. Exhibited occasionally with other Gesichter plates, Pl. 16 reveals Beckmann’s evolution in print technique and his lifelong engagement with human endurance under duress.

Reception and Influence

At its initial appearance, Gesichter Pl. 16 garnered praise within Expressionist circles for its formal innovation and emotional candor. Critics noted Beckmann’s departure from conventional narrative toward a polyphonic montage that demanded active viewer engagement. In the decades that followed, art historians have hailed the Gesichter cycle as foundational to 20th‑century graphic arts, predating and influencing Surrealist explorations of the subconscious and Dada’s embrace of fragmentation. Contemporary printmakers continue to reference Pl. 16’s layered line work and its capacity to merge personal anguish with collective history.

Contemporary Resonance

Over a century later, Gesichter Pl. 16 resonates in discussions of trauma representation, the ethics of witnessing, and the role of art in moments of crisis. Its montage of fractured bodies and allegorical motifs speaks to modern concerns—from war reportage to pandemic isolation—illustrating how the etched mark can bear witness to humanity’s darkest hours. Exhibited alongside Beckmann’s later paintings, Pl. 16 reminds viewers that graphic media can confront brutality and hope with equal force.

Conclusion

Max Beckmann’s Gesichter Pl. 16 (1914–1918) transcends the boundaries of portraiture, offering a visceral meditation on suffering, solidarity, and spiritual fracture. Through masterful etching and drypoint, he constructs a swirling assemblage of broken ladders, cruciform bodies, anguished gestures, and mask‑like faces—an allegory of wartime humanity and the quest for redemption. As a centerpiece of the Gesichter series, Pl. 16 stands as both a historical document and a timeless work of art, demonstrating printmaking’s power to channel chaos into enduring iconography.