Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

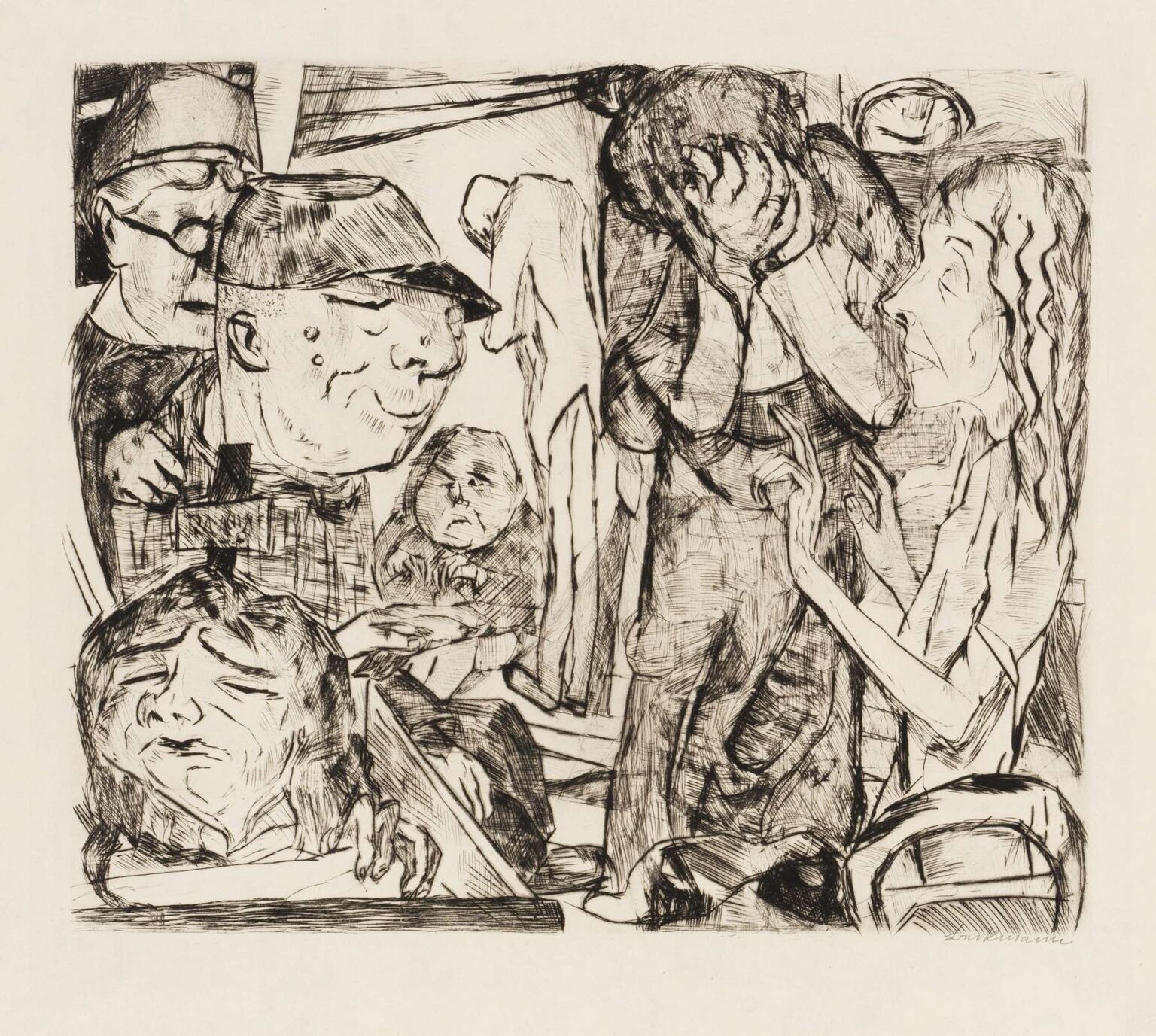

Max Beckmann’s Gesichter Pl.08, created between 1914 and 1918, represents a pivotal moment in the artist’s engagement with the human condition under duress. As the eighth image in his Gesichter (Faces) series, this etching captures a turbulent scene populated by anguished, masklike visages and contorted bodies. Far from a conventional portrait, Pl.08 unfolds as a fragmented interior drama—an ensemble of figures whose gestures and expressions evoke both personal anguish and collective despair. This analysis will examine the work’s historical context, Beckmann’s formal strategies, the symbolic import of its elements, and its place within his broader artistic trajectory.

Historical and Biographical Context

The period from 1914 to 1918 irrevocably altered Europe’s political and cultural landscape. The outbreak of World War I shattered the optimism that had fueled the turn-of-the-century avant‑garde, replacing it with disillusionment and trauma. Beckmann, born in Leipzig in 1884, was conscripted in 1915 and served in a non‑combatant capacity. Nevertheless, the experience of uniforms, military bureaucracy, and the omnipresent specter of violence left an indelible mark on his psyche. During this time, he devoted himself to printmaking—etching, drypoint, and aquatint—finding in these techniques a means to distill the psychological intensity of wartime into stark black‑and‑white imagery. Gesichter Pl.08 emerges from this crucible of personal upheaval and artistic reinvention.

The Gesichter Series and Its Evolution

Beckmann conceived the Gesichter cycle not as a linear narrative but as a thematic anthology, each plate probing different facets of fractured identity. Early plates focused on isolated masks and decontextualized heads; mid‑cycle works assembled witnesses and ritual figures; by Plate 08, the series reached a crescendo of emotional complexity. Here, the motifs coalesce into a scene that blends the interior setting of Plates 06 and 07 with a dynamic interplay of figures that verge on theatrical staging. The series thus functions as a graphic symphony, each etching offering a distinct movement in Beckmann’s exploration of trauma, alienation, and the performative aspects of social roles.

Visual Description and First Impressions

At first glance, Gesichter Pl.08 presents an almost chaotic arrangement of six principal figures within a shallow pictorial space. In the foreground, a half‑submerged head rests on a low ledge, its eyes closed and features slack with sorrow or exhaustion. Directly behind, a large, round‑faced man in a cap—with sweat beads etched onto his cheeks—offers a roughed‑in cross‑shaped structure. To the left of him, an older man with bulging spectacles and a tall hat peers over his shoulder, his gaze inscrutable. A small child sits between these two, clutching a platter or tablet, eyes wide with anxiety. At center right, a standing figure bows under the weight of hidden anguish, both hands covering his face, while a woman to his right holds her fingers in a tentative gesture as if pleading or supplicating. A clock peeks above the woman’s head, hinting at the passage of time in this fractured moment. The cumulative effect is one of simultaneous intimacy and disquiet, as if the viewer has stumbled upon a family in the throes of revelation or collapse.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Beckmann orchestrates Pl.08 around an almost symmetrical grouping of heads and torsos, yet the sense of balance is undermined by jagged lines and abrupt visual shifts. A pyramidal structure emerges: the child’s head forms the apex, flanked by the caps of the two men on either side, descending to the reclining visage below. To the right, the standing and seated adult figures provide a counterpoint to this cluster, their verticality pushing against the horizontal ledge at the bottom. Empty space at the upper left and right corners frames the scene, creating visual breathing room even as the central mass remains densely packed. The shallow depth compresses the figures against the picture plane, intensifying the claustrophobic atmosphere and inviting the viewer to confront the group’s collective emotional weight.

Line Quality and Etching Technique

Beckmann’s facility with etching and drypoint is evident in the variety of line textures. The cross beams of the cross structure are rendered with confident, angular strokes, while the large man’s sweat drops appear as delicate dots and dashes. The older man’s spectacles shimmer through fine diagonal hatchings, and the child’s chubby cheeks emerge from gently curved lines. Drypoint burr lends softness to the child’s rounded form and to the reclining head’s hair, creating tonal warmth amidst the stark black‑and‑white contrast. The standing figure’s coat is built from overlapping, grainy hatchings, giving a sense of weight and shadow. These varied techniques—etching’s precision and drypoint’s velvety burr—combine to produce an image that is both formally rigorous and deeply expressive.

The Motif of Faces and Masks

As in other plates, faces in Pl.08 function as both individual identities and archetypal masks. The child’s innocent countenance contrasts with the sweating man’s exaggerated features, suggesting a spectrum of psychological states: anxiety, bravado, weariness, and shame. The masked quality of the large man’s jowly face—accentuated by his cap and the sweat beads—hints at the performative postures individuals adopt under stress. The older man’s spectacles become a barrier between self and world, reducing the eyes to reflective surfaces. In this assembly, the face is never merely a physiological fact but a symbol of inner turmoil, of self‑protection and self‑exposure in equal measure.

Symbolic Elements and Religious Allusion

The cross‑shaped structure held by the sweating man introduces a potent symbol: the cruciform as a signifier of suffering, sacrifice, and redemption. Yet Beckmann subverts straightforward religious reading by situating the cross among quotidian objects and domestic figures. The child’s platter may allude to communion or sustenance, while the clock hovering above the woman’s head evokes the inexorable passage of time—even in moments of crisis. Together, these symbols weave a tapestry of spiritual dislocation: a scene in which the promise of salvation is entangled with the mundane and the traumatic.

Psychological and Existential Dimensions

Drawing on contemporary interest in psychoanalytic thought, Beckmann’s print can be read as a visualization of collective anxiety. The figures fail to form a coherent narrative; instead, each seems caught in a private reverie of dread. The child’s wide-eyed stare suggests primal fear; the sweating man’s bluster masks insecurity; the standing figure’s hidden face expresses shame or grief; the woman’s raised hands hint at supplication or disbelief. The reclining head, with its closed eyes, embodies surrender to exhaustion or resignation. This kaleidoscope of psychic states distills the fragmentary nature of wartime trauma, in which coherent storylines dissolve into isolated moments of emotional intensity.

Theatricality and Performance

Beckmann’s background in theater design informs the stage‑like arrangement of Pl.08. The etching resembles a proscenium scene: a cluster of actors frozen mid‑gesture under the glare of an unseen footlight. The clock at the upper right could signal both real time and dramatic time, underscoring the performative tension. The central cross becomes a prop laden with ritual significance. Even the child, clutching a platter, appears to play a role in a grotesque pageant of suffering. This theatrical dimension aligns with Beckmann’s later work, where stagecraft and allegory merge to interrogate the masks people wear in public and private life.

Beckmann’s Artistic Evolution and Innovation

Gesichter Pl.08 marks a maturation of Beckmann’s printmaking approach. His early etchings from 1912–1913 reveal a lighter, more decorative hand, while wartime plates embrace denser textures and sharper contrasts. In Plate 08, he pushes the medium’s capacities by combining multiple intaglio techniques—etching for crisp outlines, drypoint for burr, and selective cross‑hatching for tonal depth. This formal complexity mirrors the thematic complexity of the scene: a nexus of age, innocence, masculinity, and femininity, all converging in a confined space. The work’s innovative layering of line makes it a forerunner to Beckmann’s postwar compositions, which similarly deploy interlocking forms to convey psychological states.

Relation to Expressionism and New Objectivity

Although Beckmann is often grouped with German Expressionists, his printmaking in Gesichter Pl.08 exhibits a measured restraint uncommon in that movement. He avoids the brutally gestural brushstrokes of Kirchner or Nolde, opting instead for controlled, varied lines that suggest both emotion and clarity of form. Conversely, he does not fully embrace the New Objectivity’s detached precision. Instead, Beckmann forges a hybrid: a graphic style that is at once disciplined and charged with existential angst. This unique stance positions him as a transitional figure in twentieth‑century art—one who straddles emotional urgency and formal rigor.

Interior Space as Psychological Landscape

Beckmann transforms the etching’s simple interior into a symbolic milieu. The ledge bearing the reclining head evokes a stage apron; the cabinet and clock reference domesticity and time’s unrelenting flow. Yet the room’s boundaries dissolve under the weight of emotion, as figures seem to press forward into the viewer’s space. This compression of setting and psyche turns the interior into a projection of collective consciousness—a place where private fears become projectors of shared suffering.

Reception, Censorship, and Legacy

During the Weimar Republic, Beckmann’s prints found acclaim among progressive collectors but drew suspicion from conservative critics. Under the Nazi regime, works like Pl.08 were labeled “degenerate” and removed from public view. Following his emigration, Beckmann’s graphic oeuvre gained renewed attention in the United States, influencing American printmakers grappling with war’s aftermath. Today, Gesichter Pl.08 is recognized not only for its technical mastery but also for its unflinching portrayal of human vulnerability—a testament to art’s capacity to give form to collective trauma.

Conclusion

Max Beckmann’s Gesichter Pl.08 transcends its medium to offer a multifaceted exploration of identity, suffering, and performative tension. Through an intricate interplay of composition, varied line work, and symbolic resonance, Beckmann transforms a modest interior into a stage of universal significance. Each figure—child, sweating man, masked elder, shrouded adult, and pleading woman—embodies a facet of wartime anguish, while the cruciform and clock anchor their pain in spiritual and temporal dimensions. As part of his Gesichter series, Plate 08 stands as a summit of Beckmann’s wartime printmaking and a foundational influence on his later paintings. It remains a powerful reminder that art can illuminate the darkest recesses of collective experience and human resilience.