Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

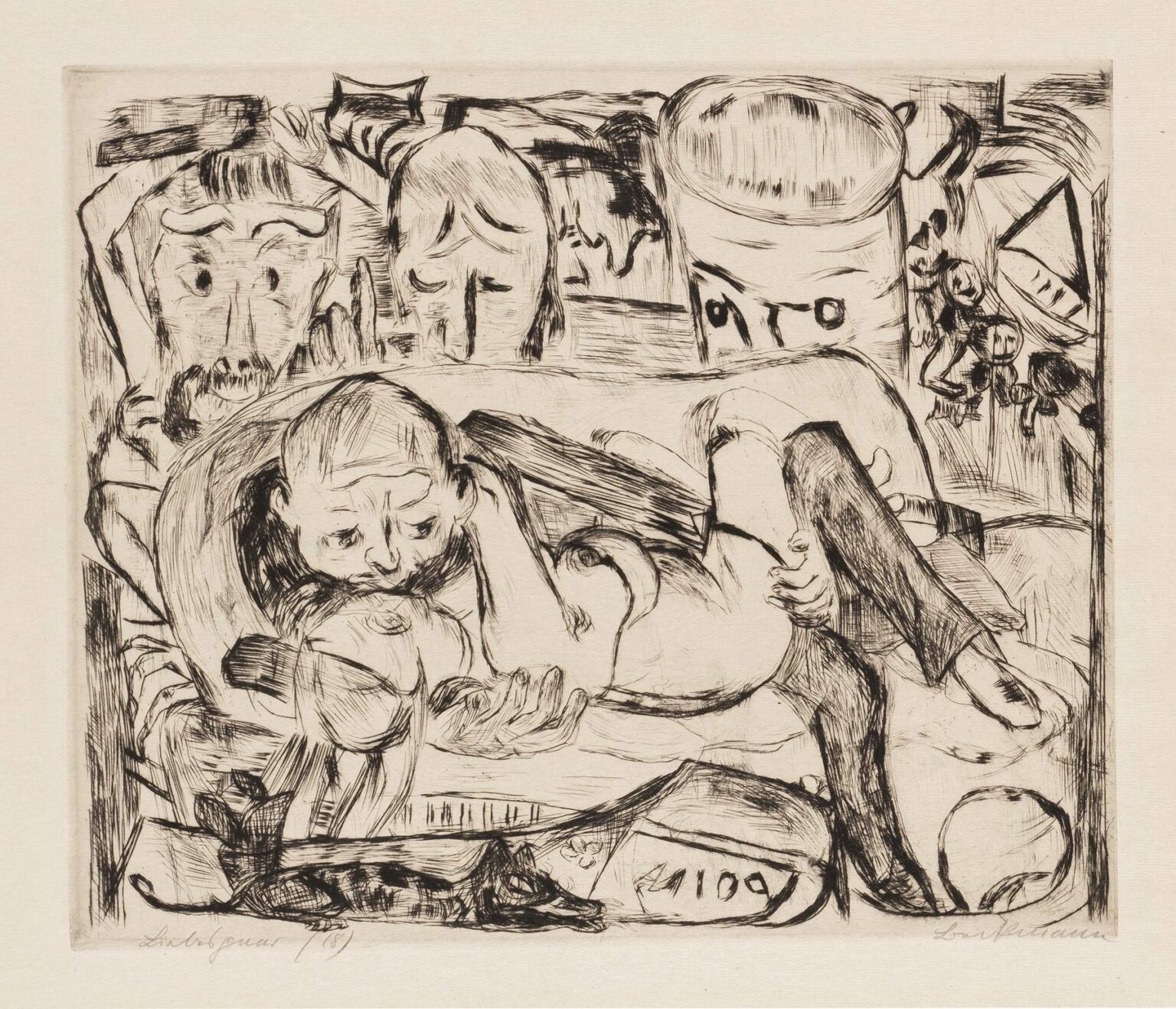

Max Beckmann’s Gesichter Pl.06, etched between 1914 and 1918, is at once a compelling formal exercise and a searing testament to the psychological fractures wrought by war. In this print, Beckmann assembles a host of visages—some rendered in stark profile, others masklike and distorted—into a compact, ambiguous setting. The result is neither a portrait nor a narrative scene in the conventional sense, but rather a meditation on the human capacity for bearing witness, enduring trauma, and negotiating identity amid upheaval. Over the course of this analysis, we will unpack the work’s historical context, explore its formal strategies, and trace the layers of symbolic resonance that make Gesichter Pl.06 a cornerstone of Beckmann’s graphic oeuvre.

Historical and Biographical Context

When World War I erupted in 1914, Europe’s artistic avant‑garde found itself confronting the most devastating conflict in human history to that point. Max Beckmann, born in 1884 in Leipzig, was conscripted in 1915. His military service, far from glorifying heroism, exposed him to the brutality and absurdity of trench warfare. Although his official duties did not place him directly on combat lines, the pervasive atmosphere of fear, injury, and loss penetrated his psyche. During these years, he produced sketches and prints that refracted lived experience through a lens of existential unease. Gesichter Pl.06 belongs to this wartime period, when Beckmann’s earlier flirtations with Jugendstil ornamentation and loose expressionist coloring gave way to a more restrained, incisive line vocabulary. The etching is thus embedded in the twin currents of personal trauma and artistic reinvention.

The Gesichter Series and Its Genesis

Beckmann’s fascination with the human face as locus of inner conflict finds its apex in the Gesichter (Faces) series. Unlike a sequential narrative, the series functions as a thematic cycle: each plate isolates specific configurations of heads, masks, and corpses. In the studio, Beckmann experimented with etching, drypoint, and aquatint, valuing the medium’s immediacy and capacity for tonal nuance. He often worked on multiple plates concurrently, transferring motifs from one to the next. Pl.06 likely emerged from such iterative play, wherein a masklike countenance first scratched in drypoint reappears, inverted or fragmented, on another plate. This restless recombination of elements underscores Beckmann’s conviction that printmaking could capture the fluid, often contradictory textures of modern subjectivity.

Visual Description and First Impressions

At first glance, Gesichter Pl.06 arrests the viewer with its packed composition. Dominating the foreground is a reclining figure whose bent form, seen in three‑quarter view, occupies the lower half of the print. The figure’s head, bowed in what might be grief or exhaustion, seems to cradle another, smaller face nestled against its chest. Above this tableau, a row of five distinct heads—some helmeted, some draped—peer forward, their gazes unsettling in their intensity. To the right, an oval object suggests a drum or barrel, while scattered angular shapes and the odd coquettish flourish of floral motifs enliven the margins. The visual economy of the etching—every line deliberately placed—creates a charged atmosphere of intimacy overlapped by collective scrutiny.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Beckmann arranges Gesichter Pl.06 in two principal registers: a lower narrative zone and an upper gallery of faces. The reclining figures inhabit a shallow, undefined interior, their limbs folding in on themselves and drawing the viewer’s eye back toward the central cluster. Above, a horizontal band of heads interrupts the pictorial space like a theatrical proscenium, as though the viewer spies both actors and audience simultaneously. This dual‑register structure resists a straightforward reading of spatial depth; instead, it suggests a collapsing of interior and exterior, private anguish and public spectacle. The composition’s tight framing enhances the sensation of claustrophobia, as if the figures cannot escape the gaze of the assembled faces or the confines of the print’s border.

Line Quality and Printmaking Technique

Beckmann’s command of etching technique is evident in the dynamic interplay of line weights. Fine, delicate hatches articulate facial planes and subtle shadows, while abrupt, jagged strokes mark the hollows of eyes or the contours of limbs. Drypoint burrs lend soft halos around certain lines, generating warm tonal passages that counterbalance the stark linearity. The tension between densely cross‑hatched areas and expanses of untouched paper produces a chiaroscuro effect that feels both graphic and painterly. Beckmann refrains from superfluous ornament; every flourish—from the curling tendril of a floral motif to the serrated outline of a mask—serves to heighten emotional resonance.

The Motif of Faces and Masks

In Beckmann’s work, the face functions as a site of self‑exposure and concealment. Some countenances in Pl.06 wear stylized masks: flattened visages with hollow eyes and exaggerated features that recall carnival and commedia dell’arte. Others appear fleshy and half‑formed, their expressions caught between anguish and resignation. The repetition and variation of these visages evoke ritual gatherings—perhaps funerary rites or masked balls—where anonymity coexists with identification. The masks may signal societal roles, protective façades, or the fragmentation of identity under duress. By juxtaposing genuine and masklike heads, Beckmann highlights the precarious boundary between authentic self and imposed persona.

Symbolism and Theatrical Allusion

The term Gesichter—faces—invites associations with theater, spectacle, and collective voyeurism. The arrangement of heads in an upper register resembles an amphitheater’s spectatorship; yet here the observers and the observed occupy a shared, ambiguous realm. The central reclining figure might be read as a performer laid bare, its vulnerabilities exposed to an impassive audience. Alternatively, the print recalls religious iconography—an inverted Pietà, perhaps—in which the central figure cradles a smaller head like a Christ child. This echo of sacred representation intensifies the tension between life‑affirming tenderness and the brutality of war’s aftermath.

Psychological and Existential Dimensions

Drawing on contemporaneous interest in psychoanalysis, Beckmann’s etching can be seen as a landscape of the unconscious. The multiple faces represent fragmented aspects of the self—ego, id, superego—caught in dialectical relation. The reclining form, with its bowed head, suggests a psyche weighed down by memory and shame. The blank spaces within the composition—unmarked areas of paper—function like Lacanian real: the unspeakable trauma that resists symbolization. Through this lens, Gesichter Pl.06 becomes not only a witness to external violence but also a probe into the interior ravages of conflict and the human impulse toward self‑recreation.

Beckmann’s Artistic Evolution and Intertextuality

Gesichter Pl.06 marks a decisive point in Beckmann’s trajectory from decorative Jugendstil to the starker iconography of his mature period. Earlier works, such as his 1912 lithographs, reveal freer, curvilinear forms; by contrast, Pl.06 embraces angularity and compressed space. Yet echoes of his prewar style persist in the ornamental tassels and floral sprigs at the margins. These residual motifs suggest Beckmann’s ongoing dialogue with his own past, refracted through the prism of wartime experience. Furthermore, elements from Pl.06 reappear in his later paintings—contorted limbs, masklike faces, and claustrophobic interiors—underscoring the print’s role as an incubator for themes that would define his postwar masterpieces.

Comparative Context within Expressionism and New Objectivity

Although often associated with German Expressionism, Beckmann maintained a critical distance from manifestos and art groups. His Gesichter series shares with Expressionist prints a willingness to distort anatomy and convey psychological tension, yet it lacks the overt painterly brushwork typical of artists like Kirchner or Emil Nolde. Nor does it align fully with the New Objectivity’s cool, detached realism. Instead, Beckmann occupies a liminal position: his forms are both jagged and measured, his subject matter allegorical yet intensely personal. This hybridity reflects his conviction that art must neither abandon emotional urgency nor sacrifice formal discipline.

Reception and Legacy

In the years immediately following the war, Beckmann’s prints circulated among avant‑garde collectors but received scant critical attention in conservative German art circles. It was not until the Weimar era that his graphic work, including Pl.06, began to be recognized for its formal innovation and moral weight. Under National Socialism, Beckmann’s art was condemned as “degenerate,” and many of his prints were seized. After emigrating to the Netherlands in 1937 and later to the United States, he witnessed a resurgence of interest in his etchings among American collectors and institutions. Today, Gesichter Pl.06 is celebrated as a prescient meditation on war’s aftermath and a key example of printmaking’s capacity to translate personal trauma into universal imagery.

Conclusion

Max Beckmann’s Gesichter Pl.06 transcends its medium to become a profound exploration of human vulnerability, collective witness, and the fractured self. Through tightly orchestrated composition, masterful line work, and recurring motifs of masks and faces, Beckmann transforms the etching plate into a stage of existential drama. The print’s layered symbolism—drawing on religious allusion, theatrical spectacle, and psychoanalytic thought—invites viewers to confront the myriad ways identity can splinter under crisis. As both a historical relic of wartime disillusion and a timeless study of psychological resilience, Gesichter Pl.06 secures its place in the pantheon of twentieth‑century graphic art.