Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

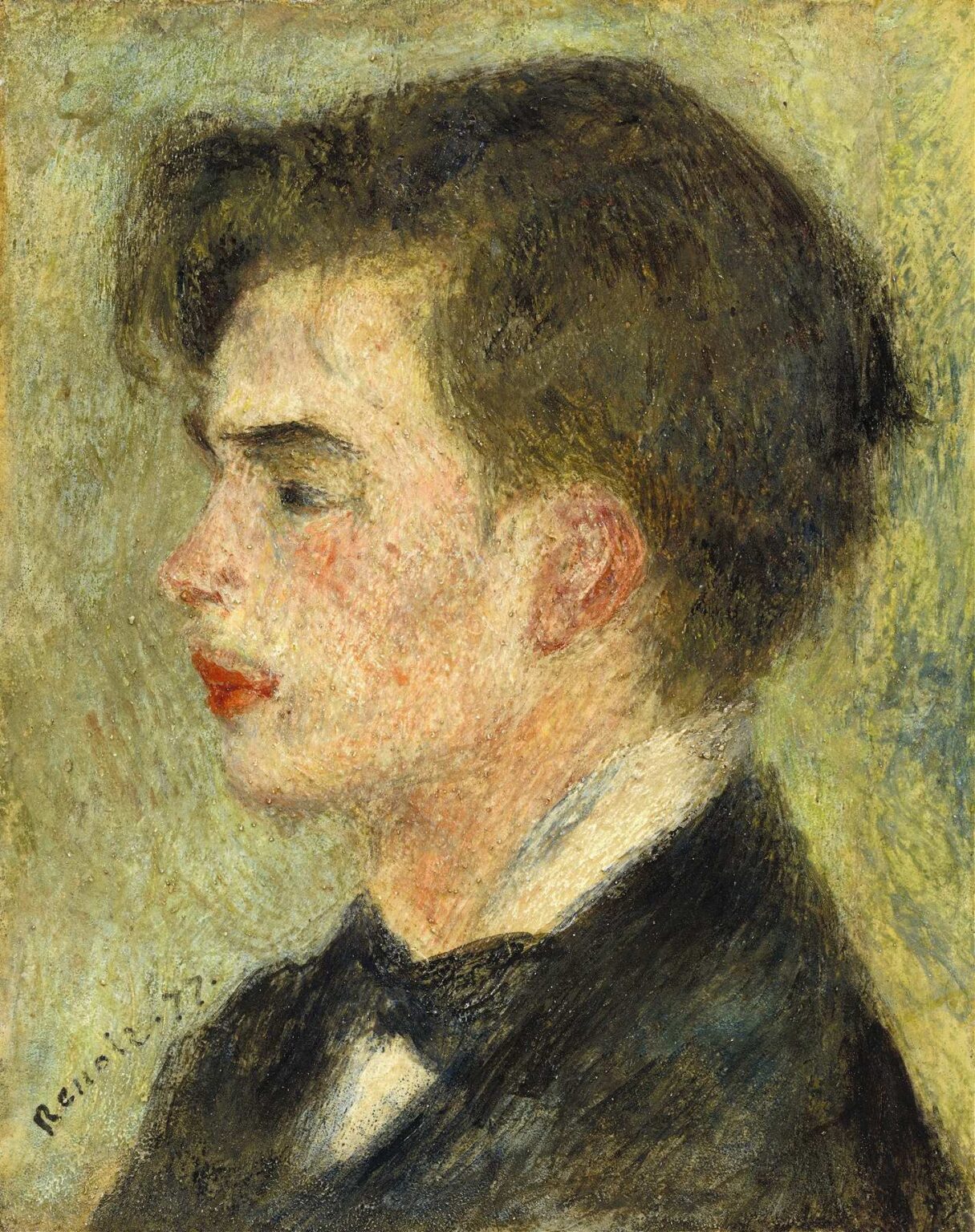

Pierre‑Auguste Renoir’s Georges Rivière (1877) captures a fleeting moment of bourgeois elegance and youthful grace in the early days of Impressionism. Rendered in oil on canvas, this portrait depicts the dashing young journalist and writer Georges Rivière—Renoir’s friend and companion in the vibrant café and salon circles of 1870s Paris. While Renoir had already begun exploring the effects of natural light and broken color outdoors, this intimate interior study demonstrates his ability to adapt Impressionist techniques to portraiture. Through a detailed examination of subject matter, compositional structure, chromatic strategy, brushwork, modeling of form, psychological insight, and historical context, we will uncover how Georges Rivière exemplifies Renoir’s capacity to balance spontaneity with refinement, and why it remains a pivotal work in the artist’s oeuvre.

Historical Context: Paris in the Late 1870s

The mid‑1870s marked a period of radical change in French art. The turmoil of the Franco‑Prussian War and the Paris Commune had given way to the Third Republic, and artists sought new ways to engage with modern life. The Impressionist group—Monet, Degas, Pissarro, and Renoir among them—organized independent exhibitions outside the conservative Salon system in 1874, challenging academic conventions. By 1877, the year Renoir painted Georges Rivière, Impressionism was gaining traction: its emphasis on direct observation, fleeting light effects, and contemporary subjects resonated with a society eager to celebrate leisure and urban vitality. In this climate, portraiture offered a bridge between the old regime of official commissions and the new art of capturing unguarded moments.

Subject Matter: The Man Behind the Canvas

Georges Rivière (1850–1905) was a noted journalist, art critic, and novelist who frequented the intellectual cafés of Paris. As a regular attendee at gatherings of the Impressionists, he provided Renoir with entrée into literary and theatrical circles. In Georges Rivière, Renoir portrays his friend wearing a dark jacket, white shirt, and black bow tie—attire that conveys both respectability and casual ease. Rivière’s head is turned in profile, his gaze directed to the left as if caught in mid‑conversation. The painting thus becomes a record of social exchange, suggesting the lively interplay of personalities that animated Renoir’s circle.

Composition and Spatial Design

Renoir composes the portrait within a tightly cropped format, focusing almost exclusively on the sitter’s head and shoulders. This close framing eliminates extraneous detail, directing the viewer’s attention solely to Rivière’s expression and posture. The background is a swirling array of warm ochre and cool green strokes, applied in Renoir’s signature broken‑color style. Instead of a flat backdrop or meticulously rendered interior, these painterly marks evoke the ambient glow of a cafe lantern or the reflection of light off patterned wallpaper. The diagonal tilt of Rivière’s head and the sweep of his dark hair create dynamic lines that contrast with the vertical edge of his collar and jacket lapel, imparting a sense of poised motion frozen in time.

Color Palette and Light Treatment

In Georges Rivière, Renoir employs a restrained yet nuanced palette. Flesh tones are built from layered glazes of rose, cream, and soft peach, with subtle touches of lavender and green for shadowed areas. Rivière’s dark hair and jacket incorporate dabs of deep blue, violet, and warm brown, avoiding flat blackness and instead capturing the play of light on textured surfaces. The background’s interplay of yellow ochre, pale green, and muted gray establishes an atmospheric aura that both contrasts with and complements the sitter. Renoir’s broken‑color brushwork allows fragments of ground color to shimmer through, imbuing the canvas with a vibrating luminosity that suggests the flicker of gaslight or candlelight in a late‑night salon.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Renoir’s brushwork in Georges Rivière marries spontaneity with deliberation. The sitter’s facial features—eyes, nose, lips—are rendered with relatively small, controlled strokes that achieve clarity without excessive detail. In contrast, the hair, jacket, and background are handled with freer, broader marks. Each stroke is visible, conveying texture and movement: the soft swirls of hair, the coarser weave of fabric, and the shimmering planes of color behind the figure. This interplay of tight and loose handling exemplifies Renoir’s late‑1860s adaptation of Impressionist techniques to portraiture, where the illusion of immediacy coexists with careful attention to form.

Modeling of Form and Anatomy

Despite the rapidity of his brushwork, Renoir never sacrifices anatomical accuracy. Rivière’s profile is carefully modeled: the forehead slopes gently into the bridge of the nose; the cheek curves softly into the jawline; the ear sits at the correct height. Subtle shading beneath the lower lip and in the hollow between jaw and neck conveys three‑dimensional volume. Similarly, the white shirt collar wraps around the neck with believable folds, suggesting crisp fabric caught in the sitter’s poised posture. Where academic portraitists relied on layers of glazing and finely blended transitions, Renoir achieves volume through cross‑hatching strokes of complementary hues—cool beneath the chin, warm on the cheekbones—demonstrating his maturing mastery of form through color.

Psychological Insight and Emotional Presence

While many portraits of the era aimed for grandiosity or idealization, Georges Rivière captures a moment of thoughtful engagement. Rivière’s gaze is neither vacant nor entirely directed at the viewer; instead, it seems cast toward an unseen interlocutor, as if he is listening and poised to respond. His lips are closed but not rigid, hinting at a personality rich with wit and intelligence. Renoir’s ability to convey this inner world—through a slight arch of the brow, the relaxed tilt of the head, and the gentle flush of the cheeks—imbues the portrait with warmth and humanity. The result is a likeness that transcends mere likeness; it offers a window into character and social rapport.

Relation to Early Impressionist Practice

Although executed in a controlled studio setting, Georges Rivière shares many hallmarks of the plein‑air studies that populated Impressionist exhibitions of the late 1870s. Broken color, dynamic brushwork, and an interest in atmospheric light infuse the canvas with energy. Unlike Monet’s landscapes or Renoir’s bathing scenes, however, this portrait remains firmly in the realm of figuration and social engagement. It demonstrates how Impressionist innovations could enliven traditional genres—landscape, still life, and portraiture—without sacrificing the sitter’s dignity or the artist’s technical rigor. Georges Rivière thus occupies a pivotal place in Renoir’s development: it reveals the artist’s confidence in blending modern technique with conventional subject matter.

Textile and Costume: Indicators of Social Status

Rivière’s attire—black bow tie, crisp white shirt, dark jacket—conveys his middle‑class standing and professional identity. In 19th‑century Paris, such evening wear signaled membership in urban urbanity’s cultured circles. Renoir renders these textiles convincingly through swift, overlapping strokes: the shirt’s starched collar glows with iridescent whites and pale blues, while the jacket’s folds absorb deeper, muted tones. These painterly decisions not only capture the play of light but also hint at the tactile quality of silk, cotton, and wool. By emphasizing the sitter’s sartorial elegance alongside his countenance, Renoir situates Georges Rivière within a cultural milieu where appearance and artistic discourse intertwined.

Technical Execution and Conservation Status

Georges Rivière is painted on a medium‑weight canvas primed with a warm buff ground. Examination under infrared reflectography reveals a light underdrawing mapping the sitter’s profile and key contours of the collar and hairline. Renoir then applied thin glazes of rose and ochre, followed by thicker applications of pigment in the flesh areas and background. The jacket and hair required multiple layers of dark paint interspersed with lighter highlights to achieve depth and sheen. Over time, aged varnish had slightly yellowed the palette; contemporary conservation efforts have removed this coating and introduced a stable, non‑yellowing varnish, restoring the original clarity of color and ensuring the painting’s longevity.

Reception and Critical Legacy

When exhibited alongside other Impressionist portraits in the 1877 and 1880 group shows, Georges Rivière was praised for its freshness and psychological acuity, though academic critics occasionally disparaged the visible brushwork. In the 20th century, art historians have recognized the portrait as a key example of how Renoir and his peers expanded the boundaries of portraiture, injecting it with immediacy and emotional resonance. Georges Rivière has influenced subsequent generations of portraitists who seek to balance fidelity of likeness with painterly expressiveness—artists as diverse as John Singer Sargent and Édouard Vuillard have echoed Renoir’s approach to light and surface. Today, the painting is celebrated not only as a likeness of a prominent 19th‑century figure but as a testament to the fusion of tradition and innovation in early Impressionism.

Comparison with Contemporary Portraits

Contrasted with formal Salon portraits—stiff figures posed before elaborately draped backdrops—Georges Rivière feels remarkably spontaneous. Whereas official portraits often involved months of sittings and over‑polished surfaces, Renoir’s Impressionist method allowed for quicker execution and greater emphasis on capturing the sitter’s mood. Compared to Monet’s 1875 The Artist’s Son, Jean Monet Reading (1872), which privileges interior light and familial intimacy, Georges Rivière conveys a public persona shaped by literary dialogue and social engagement. Yet both works exemplify how Impressionists adapted portraiture to reflect modern life, focusing on the effects of light and the authenticity of personal expression.

The Interplay of Light and Color Psychology

Renoir’s use of color in Georges Rivière serves not only aesthetic ends but also psychological ones. The warm background tones—soft golds merging into pale greens—wrap around the sitter, creating a sense of convivial comfort. These hues contrast with the cool shadows on the jacket and in the hair, amplifying the facial glow and drawing attention to the sitter’s gaze. By modulating chromatic intensities—brighter on the cheek, more subdued on the ear—Renoir sculpts the face through emotional color psychology: warmth suggests intellectual warmth, while cooler passages convey contemplative depth. This subtle orchestration of hue underlines the sitter’s multifaceted character as both lively conversationalist and thoughtful writer.

Conclusion

Pierre‑Auguste Renoir’s Georges Rivière (1877) exemplifies the artist’s innovative fusion of Impressionist technique with the demands of dignified portraiture. Through its dynamic brushwork, broken‑color brilliance, and psychological sensitivity, the painting transcends conventional likeness to offer an intimate glimpse into Paris’s intellectual salons. Rivière emerges not merely as a subject dressed for evening but as a living presence engaged in modern discourse, illuminated by the glow of ambient light and Renoir’s empathetic gaze. As a turning point in Renoir’s career—bridging academic roots and avant‑garde impulse—Georges Rivière endures as a masterful testament to the power of color, form, and human connection in the dawn of modern art.