Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

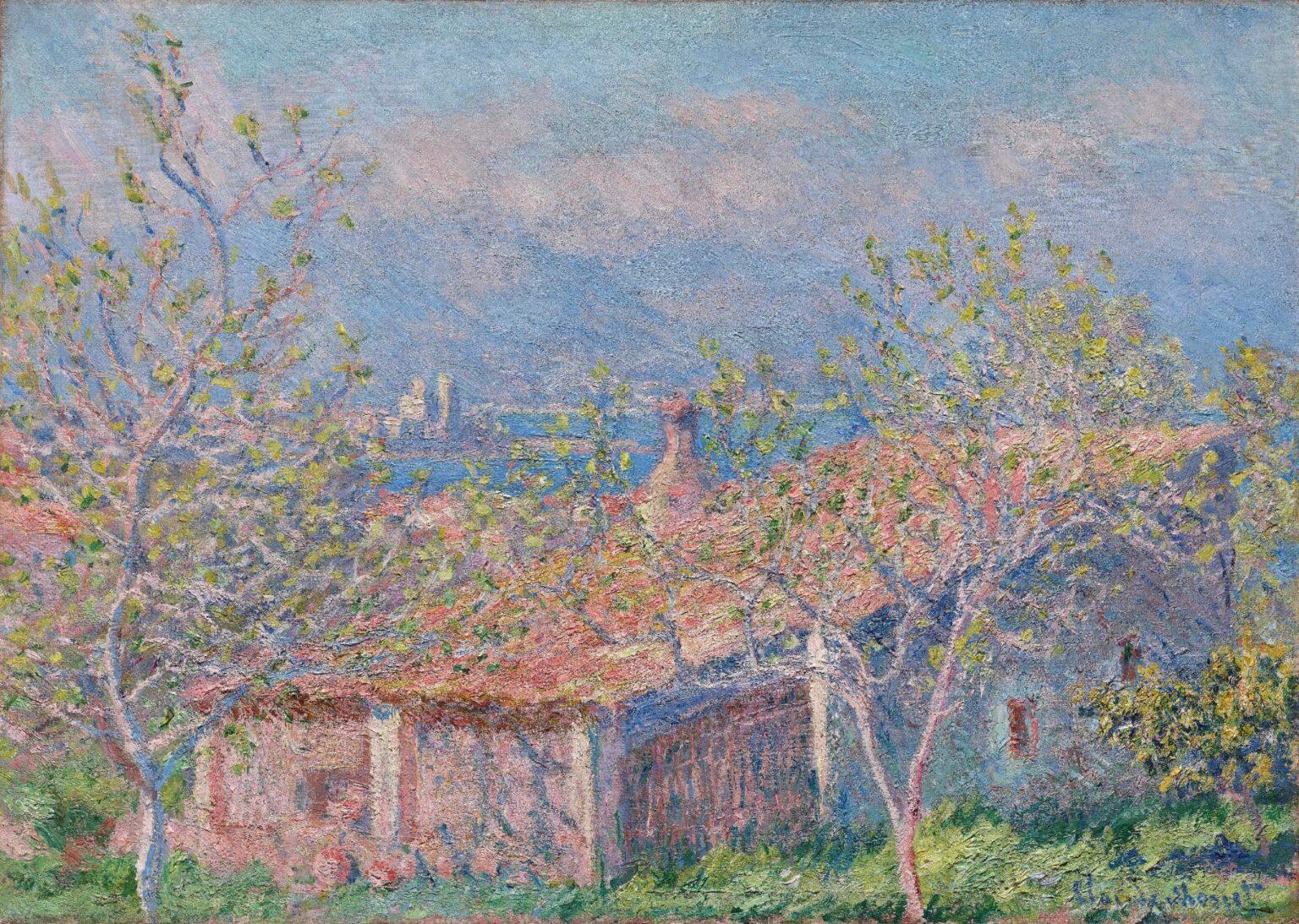

“Gardener’s House at Antibes” (1888) captures Claude Monet in the throes of his Mediterranean period, where the sun-drenched landscapes of the French Riviera infused his Impressionist palette with new warmth and vibrancy. Far from his familiar Seine banks, Monet arrived in Antibes seeking light so intense it threatened to overwhelm pigment. The resulting canvases from this 1888 sojourn reveal a painter experimenting with bolder contrasts, denser impasto, and a more saturated chromatic range while still retaining the hallmark spontaneity and atmospheric sensitivity of Impressionism. In Gardener’s House at Antibes, Monet melds architectural form, foliage, and sea vistas into a harmonious whole, offering viewers a sensory immersion in a garden awash with Mediterranean luminosity.

Historical and Biographical Context

By the late 1880s, Monet had endured personal tragedy, including the death of his first wife Camille in 1879 and ongoing financial pressures. Yet he remained restless, continuously seeking new locales to challenge his perception of light and color. In 1888, he joined fellow Impressionists Paul Signac and Édouard Manet along the Riviera, sketching and painting in Antibes, Nice, and Menton. The light on the Côte d’Azur—brighter, sharper, and more unfiltered than in northern France—compelled Monet to adapt his technique. Traditional pastels gave way to richer yellows, vermilions, and deep greens. He often worked on large canvases outdoors, translating the garden’s luxuriant growth, the house’s sunlit stucco walls, and the distant azure sea into a riot of broken color.

Subject and Setting

Gardener’s House at Antibes depicts a simple stucco bungalow nestled on a gentle slope overlooking the Mediterranean. In the foreground, young trees—possibly citrus or olive—sprout tender green foliage. Their trunks, rendered in lively pinks and lilacs, echo the warm tones of the house’s terracotta roof. Beyond the structure, a swath of deep blue sea glimmers under a cloudless sky. Through windows and shadowed doorways, hints of interior coolness contrast with the blazing exterior sun. Rather than a genteel villa, the house appears humble—a gardener’s retreat—yet Monet invests it with an almost monumental presence through his confident handling of paint and composition.

Composition and Spatial Organization

Monet structures the painting around intersecting diagonals and verticals. The horizon line sits high, allowing the house and foliage to dominate the lower two-thirds of the canvas. Diagonal brushstrokes in the roof and the sloping lawn draw the eye toward the distant sea, while the verticals of tree trunks and house columns interrupt and enliven the scene. This interplay of directions imbues the image with dynamic tension: the solidity of architectural lines contrasts with the organic fluidity of foliage, yet both are suffused by the same Mediterranean light. Monet’s choice of viewpoint—slightly elevated, looking down at the roof yet across the sea—underscores the garden’s role as threshold between land and water.

Color Palette and Light

The defining characteristic of Monet’s Antibes works is their radiant palette. In Gardener’s House at Antibes, he deploys vivid greens—from cool viridian to warm chartreuse—in the lawn and tree leaves. The house’s walls shimmer with buttery yellows and peach tones, punctuated by shadows in mauve and violet. The roof’s tiles range from rust-red to soft orange, each tile suggested through brisk, rectangular strokes. The sea beyond is rendered in bands of cobalt and ultramarine, with horizontal dashes of white denoting sunlit ripples. Monet’s daring use of contrasting complements—greeny blues against warm oranges, pinks beside muted greens—creates optical vibration, as if the painting itself were alive with heat and movement.

Brushwork and Texture

Characteristic loose brushwork animates the canvas. Monet employs varied stroke lengths and directions to differentiate materials: short, quick dabs for leaves; longer, more fluid sweeps for sky and sea; stubby, perpendicular marks for roof tiles. The paint is applied in varying thicknesses—thin glazes in the sky give a sense of translucent atmosphere, while thicker impasto on the house walls and foliage conveys tactile substance. This modulation of texture engages the viewer’s senses, inviting one to feel the roughness of stucco, the crispness of leaves, and the glimmer of distant water. Each stroke retains its individuality, yet together they coalesce into a coherent, vibrant image.

Spatial Depth and Atmosphere

Monet achieves depth through color modulation and diminishing clarity. The foreground trees and roof tiles are rendered in high detail and saturation, while the house’s far wall and the sea horizon soften into cooler tones and looser strokes. This gradation mimics how the eye perceives distance: objects near us appear sharper, those farther away blur and cool. The absence of aerial haze in the bright Mediterranean sun actually enhances this effect—shadows cast by trees are crisp, while light on distant hills fades into pale blue. Monet’s atmospheric perspective thus reinforces the painting’s sense of place, immersing viewers in the garden’s immediate brightness and the sea’s beckoning promise.

Interaction between Nature and Architecture

Unlike rigid studio compositions, Monet’s garden scenes blur the boundary between built and natural environments. In Gardener’s House at Antibes, vines and climbing plants encroach upon the house, their tendrils suggested by rapid green flicks along walls and columns. Tree branches arch over the roof, their shadows dancing on stucco in mottled purples and greens. Rather than opposing nature and architecture, Monet portrays them in symbiosis: the gardener’s abode emerges as an organic outgrowth of its setting. This integration reflects Monet’s deeper philosophy—that art should capture not static monuments but living ecosystems shaped by light, growth, and human presence.

Symbolism and Emotional Resonance

On one level, the painting celebrates the Riviera’s physical beauty—its dazzling light and lush vegetation. On another, it conveys a sense of refuge and creative sanctuary. For Monet, the gardener’s house likely represented a place of quiet labor and restful retreat amid a demanding career. The warm, inviting hues speak to comfort and domesticity, while the expansive sea view hints at freedom and renewal. The interplay of shadow and sunlight may evoke life’s dualities—work and leisure, permanence and transience. Through color and form, Monet transforms a simple cottage into a locus of emotional nuance.

Comparisons with Other Antibes Works

Monet painted several Antibes subjects in 1888, including his famed views of the harbor and ramparts. Compared to the vertical ramparts and bustling boats, Gardener’s House is comparatively intimate and domestic. It shares, however, the same Mediterranean palette and loose brushwork. In The Ramparts at Antibes, Monet’s strokes feel more horizontal and rhythmic, echoing the harbor’s walls. In the gardener’s house scene, vertical and diagonal marks dominate, reflecting the garden’s growth patterns and the house’s structure. Together, these works demonstrate Monet’s versatility in addressing both civic and private spaces under the Riviera sun.

Technical Examination and Materials

Scientific analysis of Gardener’s House at Antibes reveals Monet’s material innovations. Pigment studies identify lead white, cadmium yellow, and cobalt blue among his primary palette, combined with organic reds in the roof tiles. Infrared reflectography uncovers underdrawn outlines of trees and house eaves, indicating preliminary compositional sketches made on-site. Paint cross-sections show thin glazes over warm underlayers in the sky, enabling light to penetrate and reflect with layered luminosity. Thicker impasto adorns foliage and architectural highlights, adding tactile richness. These findings underscore Monet’s empirical approach—experimenting with novel pigments and layering techniques to capture Mediterranean light’s brilliance.

Reception and Exhibition History

Originally displayed in Paris salons in 1889, Gardener’s House at Antibes intrigued critics with its bold coloration and relaxed finish. Traditional viewers lamented its departure from meticulous detail, yet avant-garde supporters celebrated its authenticity and vibrancy. The painting passed through notable private collections before entering a major museum in the mid-20th century, where it has since been hailed as a jewel of Monet’s Riviera period. Modern scholarship emphasizes its role in broadening Impressionism’s geographic and chromatic horizons, introducing richer palettes and more expansive subject matter beyond the Seine valley.

Influence and Legacy

Monet’s Antibes works, including Gardener’s House, profoundly influenced both his contemporaries and later artists. Fauvist painters—Henri Matisse, André Derain—drew upon Monet’s lush Mediterranean palettes to explore color’s emotional power. Plein-air landscape artists across Europe and America adopted his fearless brushwork and optical mixing techniques. In the 20th century, color field painters such as Mark Rothko would revere Monet’s ability to evoke mood and light through pure color relationships. Today, Gardener’s House at Antibes stands as a cornerstone of coastal Impressionism, its innovations echoing through successive generations of landscape painting.

Conclusion

Gardener’s House at Antibes epitomizes Claude Monet’s radiant engagement with Mediterranean light, his masterful blending of architecture and nature, and his unceasing quest to record the ephemeral qualities of atmosphere through color and brushwork. The humble gardener’s cottage, bathed in warm sunshine and framed by verdant growth, becomes a luminous symbol of creative refuge and the joy of sensory immersion. Over a century since its creation, the painting continues to enchant viewers—inviting us to step into the garden, feel the Riviera breeze, and witness the transformative power of light at play across sea, stucco, and leaf.