Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

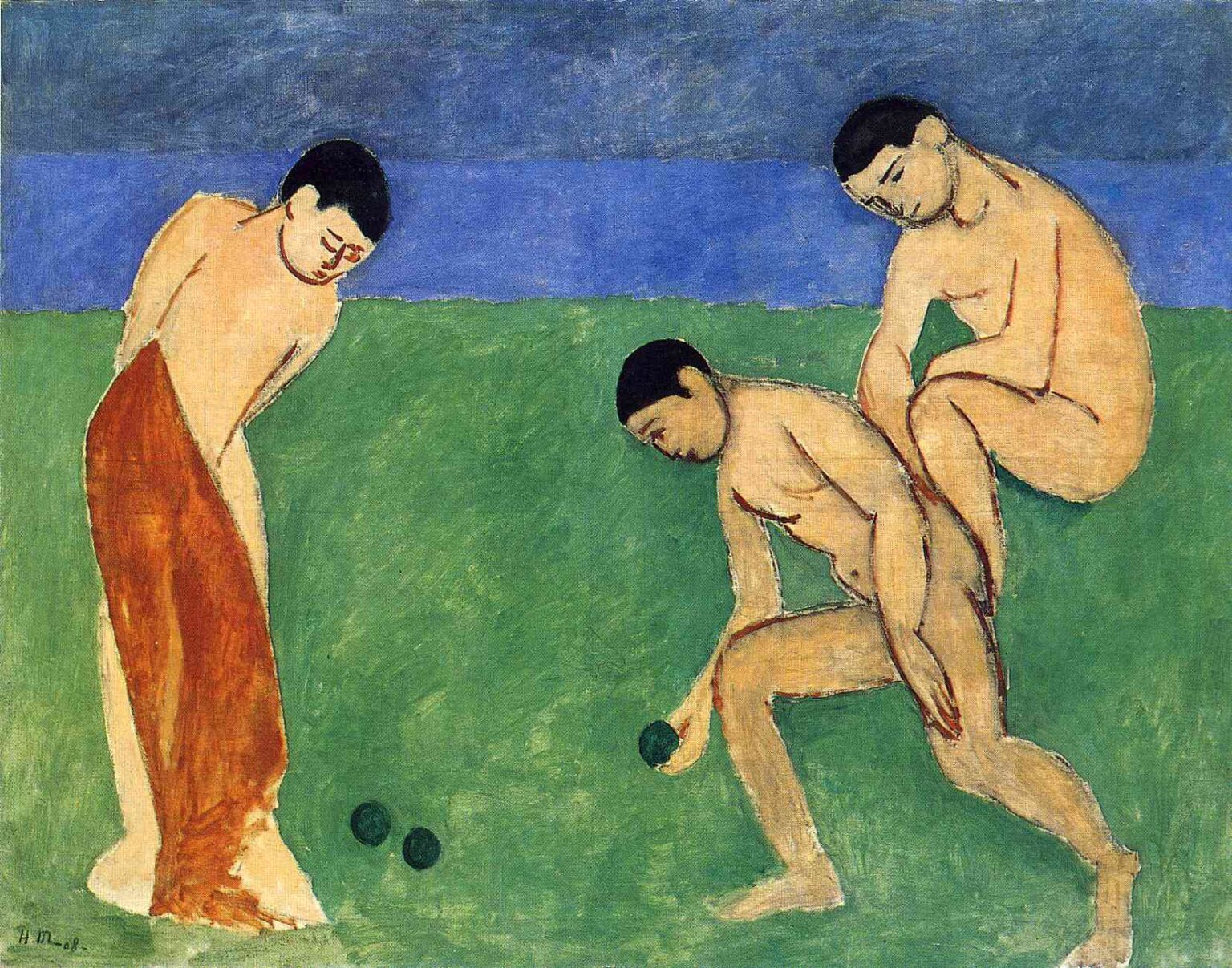

Henri Matisse’s “Game of Bowls” (1908) distills a scene of simple outdoor play into a rigorous experiment in color, contour, and compositional balance. Three nude youths occupy a wide green ground beneath a banded horizon of sea and sky. One bends to release a ball, another perches in a compressed squat, and a third, partially draped in a rust-orange cloth, inclines in quiet attention. The entire event is rendered with remarkably few descriptive means: broad planes of color, decisive dark outlines, and minimal internal modeling. The result is both serene and startling—an image that reads at once as timeless ritual and modern reduction. Created just after the most incendiary years of Fauvism, the painting shows Matisse consolidating lessons from explosive color into a calmer, more architectonic language that would culminate in masterworks like “Dance” and “Music.” “Game of Bowls” is thus not only a charming subject of Mediterranean leisure; it is a key step in Matisse’s pursuit of pictorial clarity.

Historical Context and the Turn from Fauvism

By 1908 Matisse had moved beyond the high-voltage chromaticism that shook critics at the 1905 Salon d’Automne. The blazing, discordant palette of early Fauvism gave way to a search for equilibrium—color still bold, but harnessed to structure. In writings and interviews around this time, Matisse emphasized the aim of producing an art of balance, purity, and serenity. “Game of Bowls” embodies that aspiration. The painting belongs to a sequence in which he rethought the figure in the landscape as a nearly classical motif, stripped of anecdote and placed within a stable geometry of bands and arcs. The subject—youths playing boules—anchors the modern in the ancient: an everyday pastime on the Mediterranean coast reframed as an Arcadian scene, echoing both classical friezes and the pastoral harmonies of his earlier “Bonheur de vivre.”

Composition and Spatial Design

The structure is disarmingly simple. A large, unbroken green field fills the lower two-thirds of the canvas. A narrow cobalt band reads as water; above it, a deeper blue signals the sky. The horizon sits high, flattening space and compressing depth to a shallow stage. This stage is activated by three bodies forming a wide, low triangle that stabilizes the composition. The bending figure at right drives a long diagonal through the picture, countered by the upright, draped figure at left. Between them, the crouched youth provides a hinge, his rounded back echoing the spherical bowls that punctuate the grass. These repetitions of curvature—shoulders, knees, heads, and balls—generate a gentle rhythm that replaces conventional perspective. Spatial cues come less from recession than from overlap and contour, allowing Matisse to maintain the canvas’s surface unity while still describing a convincing scene.

Color, Light, and the Logic of Planes

Color here is not the record of observed light but the organizer of sensation. The grass is not a mosaic of greens, but a single, monumental plane subtly modulated by the brush. The sea is a flat band of blue, the sky a weightier, cooler blue that deepens toward the top edge. This banding separates zones of the picture into calm, legible layers, giving the beholder a map of the scene at a glance. Against these fields, the flesh is set as a warm counter-tone—peach, ochre, and pale rose articulated sparingly by violet-brown contour. The only strong accent is the orange drapery on the left figure, a vertical flare that anchors the entire color system and measures the surrounding greens and blues. The harmony is deliberate: complementary contrasts (orange against blue, warm flesh against cool ground) are calibrated for repose, not shock. Even the bowls, dark green against green, speak softly; they are registered more by the logic of the game than by chromatic insistence.

Figures, Gesture, and the Choreography of Play

Matisse arranges the three bodies as if choreographing a slow, quiet dance. The right-hand figure bends in a long arabesque, his weight carried over the forward leg, the near arm sweeping toward the ground to release the ball. The central youth drops into a compact crouch, his gaze lowered, his spine forming an arc that mirrors the ball he contemplates. The left figure, partially wrapped, inclines in a modest bow, an observer-participant whose drapery introduces a classical note. None of the faces are individualized; hair is reduced to black caps; features are marked with a few economical strokes. What matters is the attitude—postures that are readable at a distance, communicating the calm concentration of the game. The trio’s absorbed attention establishes a mood of inwardness that belies the athletic action. This is play as meditation, a measured ritual in which time is slowed and the world’s noise recedes.

Economy of Line and the Role of Contour

Dark lines articulate the bodies with unapologetic clarity. These contours neither chase anatomical detail nor dissolve into atmospheric edges. Instead, they function like the lead cames in stained glass, containing and energizing the color within. A single stroke can define a thigh, a shoulder, the profile of a face. The line is at once structural and lyrical—firm enough to hold the composition, supple enough to sing. This economy of drawing reveals Matisse’s allegiance to the grand French tradition of Ingres and to the decorative simplifications he admired in non-Western art. The contour does not simply describe; it edits. It removes any element that would distract from the essential movement of the forms, leaving a distilled syntax of curves and arcs that invites the eye to trace them continuously across the canvas.

Surface, Brushwork, and the Presence of the Hand

Although the color fields appear simple, they are alive with the touch of the brush. The green ground bears subtle shifts and scumbles, the blue sky shows variations that keep it from becoming a dead plane. In the flesh passages, thin paint allows earlier drawing to glimmer through, giving the bodies a living vibration. Matisse avoids the labored finish of academic painting; he wants the surface to breathe. The deliberately visible hand links the painting to the time of its making. One senses decisions made and remade with speed and certainty—the laid-in horizon, the decisive placement of the balls, the drapery painted with a few broad, juicy strokes. This frankness of facture becomes a moral position: clarity over fuss, essence over anecdote.

Themes of Play, Leisure, and the Arcadian Ideal

“Game of Bowls” stands within a long European tradition of pastoral imagery, yet its modernity lies in its ordinariness. The players are not mythic shepherds or allegorical figures; they are everyday youths at play. By stripping away specific setting and costume, Matisse raises the scene to the level of archetype. The Mediterranean, famously a source of renewal for him, becomes a sign of clarity and health. Leisure here is not decadence; it is discipline, an activity measured and shared. The game’s rules—distance, aim, turn-taking—suggest social harmony and mutual attention. In this sense the painting proposes an ethic of modern life: balance between the individual body and the communal field, between free gesture and agreed order. The bounded green becomes a civic space, an arena of conviviality without spectacle.

Classicism, Primitivism, and the Nude

At the turn of the century, many avant-garde artists looked to so-called “primitive” sources—African sculpture, Oceanic carving, Byzantine icons—for alternatives to the Western naturalist tradition. Matisse synthesized these influences with a revived classicism. The nude in “Game of Bowls” is not the academic model but a simplified, timeless body. Its generalized features push against portraiture; its contour borrows from relief sculpture; its stance and gravity recall frieze compositions. The partial drapery on the left figure functions like a classical attribute, introducing a vertical foil to the abundance of curves. By blending these currents, Matisse achieves a language neither borrowed nor nostalgic. The painting is less about citing sources than about arriving at an essential human form, one that can carry feeling without psychological specificity.

The Decorative Order and Lessons from Ornament

Matisse frequently insisted that “decorative” was not a pejorative but a positive principle of coherence. In “Game of Bowls,” the decorative manifests in the even distribution of interest across the surface, the suppression of deep space, and the orchestration of repeating shapes. The ground, sea, and sky lend themselves to pattern; the figures, though volumetric, are flattened just enough to participate in a planar design. The eye can roam anywhere without encountering pictorial dead zones. This democratization of the surface is a hallmark of his art. It connects the painting to textiles, tiles, and mosaics he admired, while remaining thoroughly painterly. Ornament, for Matisse, is not applied; it arises from the disciplined repetition and variation of forms within the picture’s architecture.

Dialogues with Sister Works

Viewed alongside Matisse’s other figure-in-landscape compositions of the period, “Game of Bowls” clarifies a path toward radical simplification. The broad color zones and ritualized gesture anticipate the monumental ring of figures in “Dance.” The compression of depth and slow tempo echo the pastoral community of “Bonheur de vivre,” but with a stricter economy and a reduced cast. Even the humble motif of rolling spheres becomes a study in pictorial grammar: circles scattered across a field, in dialogue with knees, heads, and rounded shoulders. The painting thus functions as both an autonomous scene and a laboratory for larger solutions Matisse would soon deploy on a grand scale.

Process, Scale, and Material Choices

While the work’s apparent simplicity suggests ease, its poise derives from careful premeditation. The canvas scale is large enough to permit life-size rhythms without overwhelming the viewer. Matisse likely established the figure placements with a charcoal or thinned paint drawing, securing the long diagonals and primary arcs before committing to color. He then laid in the planar grounds with broad strokes, adjusting tone and saturation until the flesh registered with the required warmth. The contour, added and reinforced as needed, became the final conductor, ensuring that forms held their intervals. Nothing feels provisional; nothing feels fussy. This balance is the outcome of a painter who knows which decisions matter most.

Reception and Meaning Then and Now

Early viewers often struggled with Matisse’s refusal of descriptive detail. Yet the very qualities that once seemed reductive now register as profound. The painting asks contemporary viewers to slow down and to accept that completeness in art does not require accumulation. Its power lies in restraint: a handful of colors, three bodies, a few balls, and a horizon. From these, Matisse constructs an image that feels inexhaustible, because each element is made to carry multiple roles—spatial, rhythmic, symbolic. In a present saturated with images, the painting’s calm stands as a corrective. It models an attention that is patient, communal, and embodied.

The Psychology of Calm and Concentration

Although the faces are schematic, the painting possesses a strong psychological charge. The downward glances, the folded limbs, and the contained gestures speak to an interiority shared across the trio. Their focus on the balls is also a focus on the immediate moment. Nothing in the scene distracts: no architecture, no foliage, no spectators. The players are not energetic athletes; they are thinkers whose thought happens to move through the body. This quality of calm vigilance is contagious; the viewer, too, begins to notice small modulations—the soft edges where flesh meets ground, the way the drapery’s orange deepens as it descends, the subtle differences between the two blues at the horizon. The more one looks, the more the painting’s quiet intensifies.

Ethics of Simplification

Matisse’s simplification is not a negation of complexity but a moral stance on what to value. By paring away incident, he refuses sensationalism. He stakes the painting’s success on relationships that cannot be summarized in anecdote: hue to hue, curve to curve, weight to weight. The choice of a modest subject—a common game—underscores this ethic. Grandeur is earned not through narrative heroics but through exactness of relation. The picture invites a similar ethic in life: a turn toward the essential, an attention to what holds communities together—shared rules, shared concentration, shared time.

Modernity and the Body

The modernity of “Game of Bowls” is nowhere more evident than in its treatment of the body as both emblem and design. The nudes are neither erotic display nor academic exercise. They are components in a living structure, agents of measure within a chromatic architecture. Matisse acknowledges the body’s weight—knees bent, heels lifted, torsos canted—but he refuses to dramatize strain. The figures are light not because they lack gravity, but because their movements are perfectly economical. In this sense the painting proposes a modern ideal: a body at ease in a rational, luminous environment, free of pathos yet full of grace.

Lasting Legacy

“Game of Bowls” may appear modest next to the spectacle of “Dance,” yet its influence is considerable. Artists studying the bridge between representation and abstraction find in it a crucial example of how to maintain human presence within a flattened, decorative order. Designers and architects recognize its lesson in banded structure and interval. Painters learn from its courage to let large fields stand, to trust color to carry meaning, and to let contour perform both drawing and design. The painting continues to teach that simplicity, when earned, is inexhaustible.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse condensed a world into “Game of Bowls.” Three youths, a few spheres, a strip of sea and sky—these are the raw materials. From them he forges a whole idiom: planes that calm, contours that sing, gestures that breathe, colors that balance. The painting is an ode to measured play and communal attention, a meditation on the body’s grace in a clear world. It marks a turning point in Matisse’s journey from Fauvist shock to classical serenity, and it remains a bright, durable testament to his belief that art can be both profoundly modern and timelessly humane.