Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

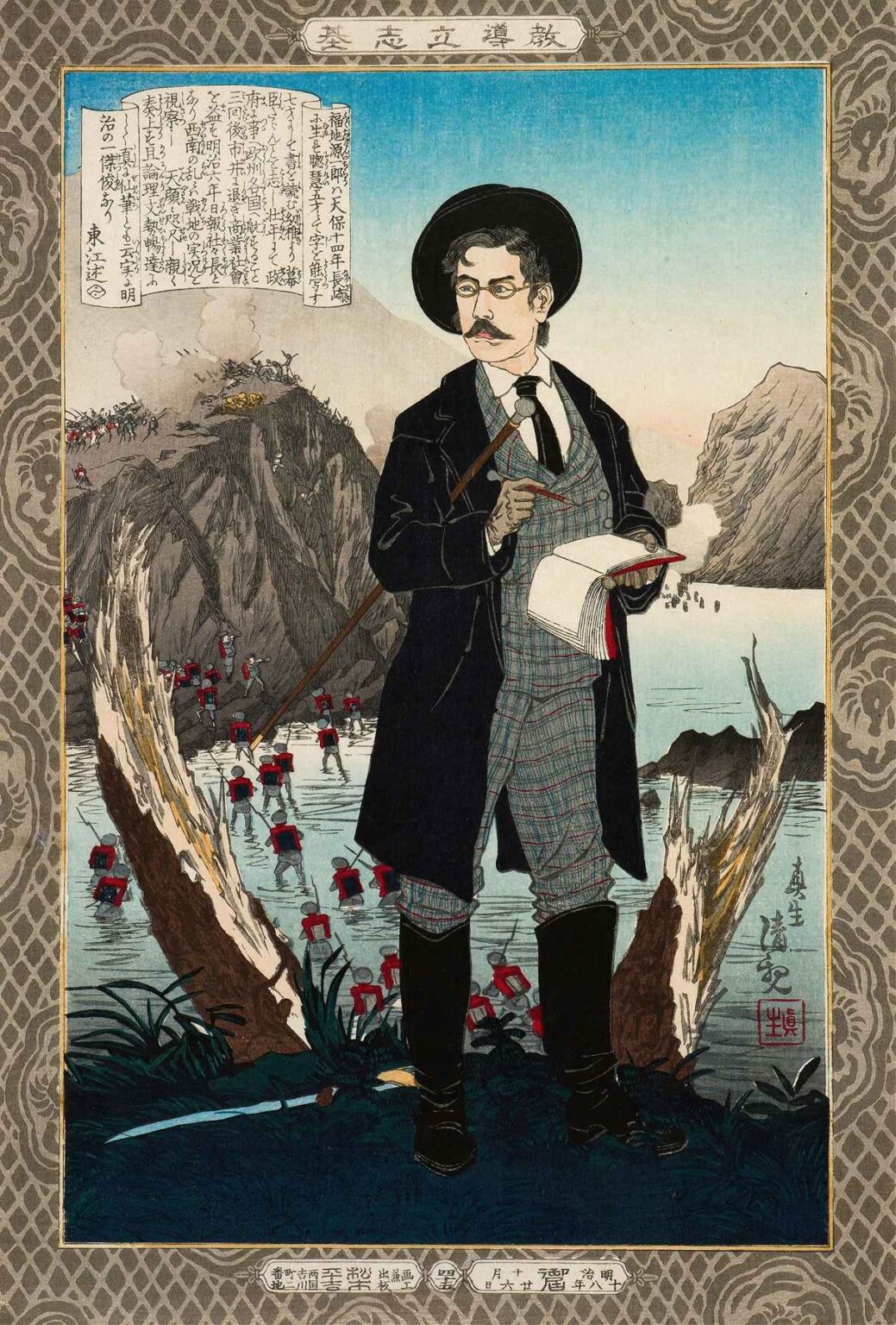

Kobayashi Kiyochika’s Fukuchi Gen’ichirō, from the series Instructive Models of Lofty Ambition is a dynamic, symbol-laden woodblock print that bridges Japan’s traditional artistic forms with the country’s rapid modernization during the Meiji era. Created in 1885, the print features the notable journalist and political thinker Fukuchi Gen’ichirō posed confidently before a dramatic wartime backdrop, notebook in hand. Part portrait, part patriotic propaganda, part aesthetic hybrid, the print exemplifies how Meiji-era art celebrated not only warriors and statesmen but also the emerging intellectual elite.

This extended analysis explores the historical background, compositional structure, cultural symbolism, and broader significance of this print, situating it within the context of both Kiyochika’s evolving style and the transformative environment of Meiji Japan.

The Meiji Era: Transformation through Turmoil

The Meiji Restoration (1868) marked a complete upheaval of Japanese social and political systems. The centuries-old Tokugawa shogunate was replaced by a central imperial government bent on modernization. The samurai class was disbanded, the feudal economy was replaced with capitalist enterprise, and the country industrialized at an astonishing pace. Western-style education, military systems, railroads, and telegraphs reshaped everyday life.

Amid this context of change and uncertainty, artists sought new ways to document, interpret, and inspire. Kobayashi Kiyochika, born into a minor samurai family in 1847, initially resisted the new order but later became one of its most vivid chroniclers. His transition from documenting Edo’s twilight to embracing Meiji’s forward march paralleled the country’s national story.

By the 1880s, Kiyochika had turned to heroic portraiture. His series Instructive Models of Lofty Ambition (Kyōdō risshi motoi) served as visual moral education—iconic figures from history and contemporary life presented as role models for modern Japanese citizens.

Fukuchi Gen’ichirō: The Intellectual as Hero

Fukuchi Gen’ichirō (1841–1906) was emblematic of the new Meiji man. Though born a samurai, his career transcended the warrior mold. He studied Western languages, supported the imperial side in the Boshin War, and rose to prominence not by sword, but by pen. As a journalist, he co-founded the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun, Japan’s first modern newspaper. Fukuchi played a critical role in shaping public opinion on issues such as civil rights, constitutional reform, and foreign policy.

Kiyochika’s depiction of Fukuchi in this series is notable not only for its subject—who was still alive at the time—but for its implicit message: that writing, communication, and intellectual courage were now equivalent to battlefield valor. In a society rapidly shifting from feudal codes to industrial discipline, Fukuchi served as a blueprint for ambition redefined.

Visual Structure: Staging the Modern Man

In the print, Fukuchi dominates the foreground, positioned slightly off-center but clearly monumental. He holds a notebook and a red pencil—tools of his trade. His posture is erect and commanding, but not aggressive. Unlike military leaders, he is not drawn mid-shout or strike. Instead, he observes, thinks, records.

Behind him unfolds a stunningly detailed battle scene. Soldiers in red coats wade through water, scale a cliff, and engage in combat on a volcanic ridge. Smoke from explosions and rifle fire rises in the distance, but Fukuchi remains grounded and untouched. This juxtaposition creates a compositional and ideological contrast: chaos versus control, violence versus intellect, spontaneity versus strategy.

Two jagged tree trunks frame the lower edge of the scene like stage curtains or torn remnants of nature. They draw the eye inward and upward, guiding the viewer through the diagonal thrust of the image—from the foot soldiers, to the action on the ridge, and finally to the calm, calculating journalist.

Western Dress and the Modern Japanese Identity

Fukuchi’s attire speaks volumes. His three-piece checked suit, knee-high boots, cravat, and bowler hat all signal his Western education and sophistication. He is not in traditional samurai robes nor modern military uniform but clad as a European intellectual—an image increasingly familiar to Meiji audiences who witnessed the adoption of Western fashion in government, media, and business.

The careful rendering of the plaid pattern reflects the printmakers’ technical mastery. Such detail was difficult to achieve in woodblock carving and suggests both pride in craftsmanship and admiration for the complexity of imported styles.

More than a fashion statement, Fukuchi’s appearance represents the conscious merging of East and West. His spectacles, a symbol of literacy and clarity, and his poised demeanor suggest that knowledge and reason are the new weapons of modern Japan.

Chiaroscuro and Atmospheric Effects

Kiyochika was known for his innovative use of light, often called kōsen-ga, or “light-ray pictures.” Inspired by Western lithographs and photography, he broke from the flat, graphic tradition of ukiyo-e to experiment with volume and shadow.

In this print, the sky transitions smoothly from light to dark, and Fukuchi’s figure is modeled with subtle ink washes that suggest dimensionality. His overcoat appears almost sculptural in its folds and heaviness. The water glistens with gradient coloring and fine line work, likely enhanced with mica powder to catch light—an expensive and advanced technique.

These visual innovations create a sense of realism and weight, grounding the viewer in a believable, contemporary world rather than a mythic or theatrical one.

The Role of the Battlefield

The background, far from mere decoration, functions symbolically. The battle could reference Japan’s 1884–85 campaign in Taiwan or even hint at the First Sino-Japanese War still to come. In either case, the image aligns Fukuchi with Japan’s imperial ambitions—not as a soldier but as a chronicler who shapes perception and memory.

Kiyochika presents the press as both eyewitness and architect of modern national identity. The soldiers’ red coats and dramatic poses echo Western illustrations, reinforcing Japan’s place among global powers while asserting visual authority through native craftsmanship.

The cliffs and water may also symbolize Japan’s physical geography and military strength—dangerous terrain, navigated by a disciplined force and witnessed by a mindful chronicler.

Textual Elements and Moral Instruction

At the top left is a block of printed calligraphy, likely a biography or encomium authored by the publisher or a contemporary essayist. These inscriptions were an integral part of the series and aligned with Meiji educational goals. Each figure in Instructive Models of Lofty Ambition was selected not merely for fame but for their instructive value.

Here, Fukuchi is not just being honored—he is being offered as an example. His personal advancement from samurai to modern journalist serves as a moral tale: one could, through study, reform, and action, contribute meaningfully to the nation’s future.

The series title at the top of the frame is printed in elegant calligraphy: Kyōdō risshi motoi—“Foundations of Aspiring to Lofty Ambition.” It echoes a Confucian ethos of public service through self-cultivation, reinforcing the image’s role in guiding the public mind.

Intersections of Art, Journalism, and Nationhood

This print marks a convergence of forces—artistic, political, and ideological. It reflects a nation striving to modernize while retaining its cultural essence. The artist, once rooted in Edo traditions, adopts new visual techniques. The subject, a journalist with samurai roots, embraces Western dress and international ideas. The medium, a woodblock print, long associated with entertainment and pleasure districts, now becomes a platform for patriotism and pedagogy.

As Japan expanded its reach into East Asia, narratives of national destiny became increasingly visual. Artists like Kiyochika helped mold public opinion through compelling, heroic depictions of individuals who symbolized transformation, diligence, and national purpose.

Preservation and Modern Interpretation

Today, surviving impressions of this print are housed in major institutions like the Harvard Art Museums and the St. Louis Art Museum. Scholars prize them not only for their beauty but for their historical insights into how Meiji Japan viewed itself. These works serve as primary sources in understanding how the press, military, and cultural elites were visually canonized.

Many of these prints suffered damage over time, particularly from exposure to light and moisture. Restoration efforts have revealed the extraordinary vibrancy and technical precision of Kiyochika’s work. Digital access now allows broader audiences to appreciate his hybrid vision of Japanese identity.

The Legacy of Kiyochika and the Series

Instructive Models of Lofty Ambition was one of Kiyochika’s most ambitious projects. Spanning 50 prints, the series included warriors, poets, scholars, and even Tokugawa Yoshinobu—the last shogun. That Fukuchi appears alongside these historical giants emphasizes how the concept of “lofty ambition” had evolved. In modern Japan, ambition meant not only military conquest but also intellectual and cultural achievement.

Kiyochika’s later work, including war prints during the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese conflicts, grew more sensational. Yet the Fukuchi print stands apart for its restraint, balance, and thoughtful composition. It reflects not just a moment in a man’s life but a moment in Japan’s redefinition of heroism.

Conclusion

Fukuchi Gen’ichirō, from the series Instructive Models of Lofty Ambition is more than a woodblock portrait—it is a mirror of Meiji Japan’s hopes, anxieties, and evolving ideals. Kobayashi Kiyochika captures a transitional figure in a transitional time, employing both traditional technique and modern perspective. Through his careful use of color, composition, and symbolism, Kiyochika celebrates a new kind of hero: not the warrior of the past, but the educated, literate, and visionary thinker shaping the future.

In a single frame, the viewer is given a battlefield, a biography, a political message, and a lesson in ambition. Today, the print continues to resonate as a testament to the enduring power of art to reflect and shape the soul of a nation.