Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

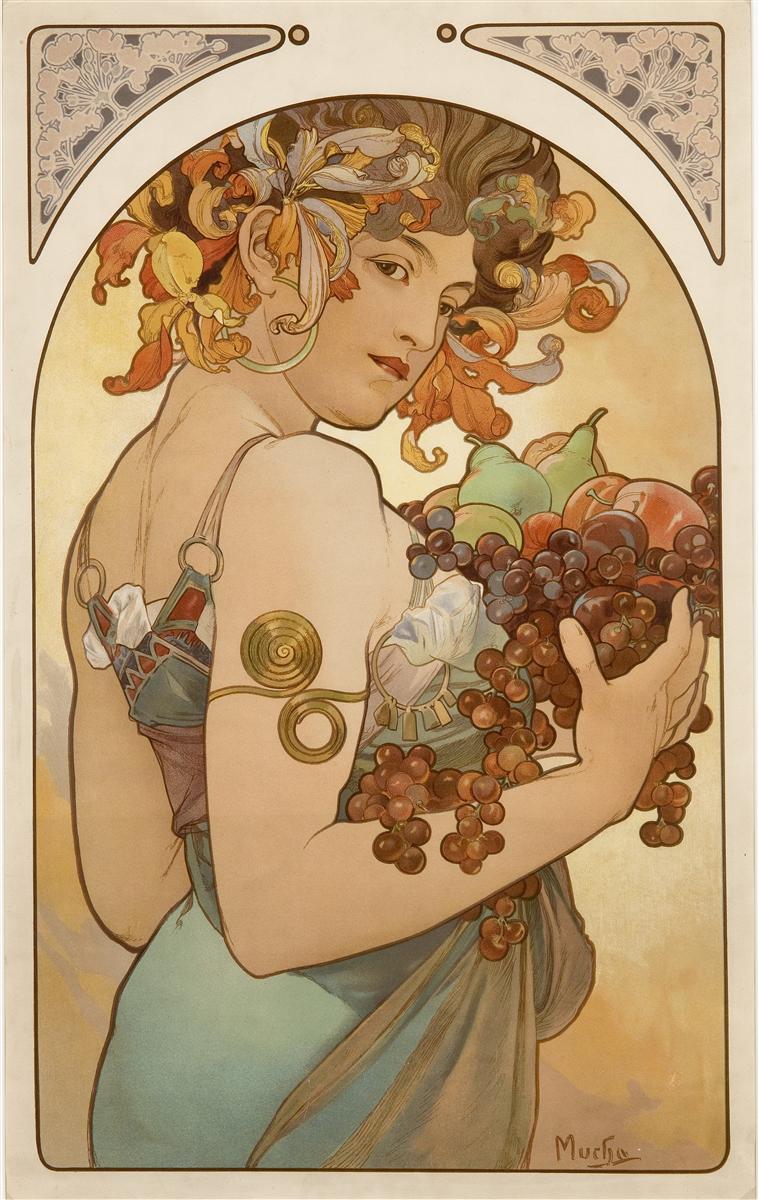

Alphonse Mucha’s “Fruit” (1897) is one of the quintessential decorative panels of the Belle Époque, a lush celebration of sensual abundance rendered with the lucid elegance that made the artist’s name synonymous with Art Nouveau. A young woman turns half away from us, glancing over her shoulder as she gathers bunches of grapes and a spill of pears, apples, and late-summer bounty against her breast. Her hair unfurls in stylized curls and floral tendrils; a crown of lilies flames above her ear; bronze armlets gleam like coiled vines. The entire scene sits within an arched frame whose corner spandrels carry pale botanical tracery, binding figure, fruit, and ornament into a single rhythmic design. “Fruit” belongs to a set of four allegories that included “Flower,” “Poetry,” and “Music,” and it distills Mucha’s art to an essence: a central heroine, a shallow stage of color, and a symphony of line that turns matter into melody.

Context and Purpose

By 1897 Mucha had already transformed Parisian street life with his posters for Sarah Bernhardt and luxury brands. In partnership with the printer F. Champenois he also created decorative panels—color lithographs issued in affordable editions, designed for private interiors rather than street hoardings. These panels were intended to hang in salons, cafés, and middle-class homes, offering a touch of glamour and a self-contained emblem viewers could live with every day. “Fruit” is such an emblem. It bears no copy or product but invites the pleasures of harvest into domestic space. The panel participates in the era’s fascination with personification, making seasons and virtues visible through idealized figures. Yet it avoids the moralizing tone of earlier allegories; here, harvest is not duty but joy.

The Decorative Panel Format

The picture plane is a tall rectangle capped by a broad arch. Within this architecture the heroine occupies nearly the full height, so that her body reads as a column supporting the whole design. Pale spandrels in the upper corners carry muted vegetal motifs that echo the colors of the figure’s dress and the fruit she carries. This framing device functions both visually and practically. It gives the sheet a clear silhouette that reads from across a room, and it standardizes the format so related panels could be sold as sets, harmonizing on a wall like verses in a song. The arched top also suggests sanctuary; harvest becomes a rite performed before a domestic altar to nature’s generosity.

Composition and the Turned Gaze

Mucha composes the figure in a contrapposto governed by the turned head. The shoulders pivot away while the face looks back, creating a gentle spiral that the eye continues through hair, armlets, and the looping stems of grapes. This turning gesture is both welcoming and teasing. The viewer is acknowledged without being fully addressed; the fruit is gathered for an unseen table, and we become complicit in the scene by completing it in imagination. The arms describe a semicircle that cradles the harvest and locks the composition to the frame. Fingers press gently into grape clusters; wrists flex with the weight. The design is entirely about the pleasure of holding and the beauty of the held.

The Language of Line

Art Nouveau lives by the eloquence of curve, and “Fruit” is pure calligraphy. Contours swell and taper as if drawn by a reed pen dipped in honey. Hair loops in tendrils that mimic vine growth; the edge of a shoulder echoes the curve of a pear; the outline of a forearm slides into the arc of a grape stem. Mucha uses line not only to describe but to orchestrate, assigning different tempos to different materials. Drapery falls in long legato folds; the cascade of grapes is staccato; the floral crown explodes in syncopated petals. Because the panel relies less on shadow than on contour, the image remains legible from a distance, yet the close viewer can follow each tiny modulation of stroke like a melody.

Color, Light, and Atmosphere

The palette favors warm earths and late-afternoon radiance: peach, apricot, and soft bronze in skin and fruit, olive and celadon in leaves and dress, a haze of pale gold in the background. The inks are matte and gently layered, avoiding harsh contrast. Modeling is accomplished through small value shifts and the authority of line. This restraint is intentional. Decorative panels needed to coexist with wallpaper, woodwork, and upholstery. Mucha’s colors flatter the room rather than overpower it, yet they vibrate with enough saturation that the fruit seems to glow from within. Highlights are often the unprinted white of the paper, allowed to gleam along a grape or pick out the nacre of a lily petal, giving the prints a luminosity that feels hand-polished rather than slick.

Costume and Ornament

The heroine’s costume is an elegant hybrid of classical drapery and folkloric detail. Thin straps clasp a bodice patterned with geometric bands; a necklace of rectangular pendants rests above the sternum; spiral armlets coil like golden shoots. Mucha’s Moravian memory surfaces here in the decorative discipline of the motifs without overwhelming the panel with ethnographic specificity. Ornament becomes character. The spirals amplify the theme of growth; the pendant necklace echoes the rectilinear motifs of Champenois’s lithographic borders, uniting body and page; the bodice’s patterned bands act as visual rests between the luxuriant hair and the profusion of fruit.

Hair and Floral Crown

Mucha’s hair is never a mere accessory; it is a weather system. In “Fruit” it surges in copper and umber waves, catching the wind of invisible movement. The floral crown—part lily, part fantastical bloom—bursts from the ear like a comet’s tail, its petals threaded into the curls. This interweaving of bloom and hair fuses woman and garden without dissolving the individuality of either. The crown’s yellows and creams pick up the tones of the background; its lilac shadows converse with the cooler notes in the dress; and its pointed petals counter the roundness of grapes and apples. Everything is balanced, interlocked, and alive.

The Fruit as Symbol and Sensation

Grapes dominate the harvest, their rounded forms repeating in clusters that echo the curl of hair and the rhythm of the armlets. Grapes carry classical associations of autumn and abundance, of Dionysian revel and the sweet intoxication of ripeness. They also offer the printmaker a chance to play with dots of color and highlight, each berry a tiny sphere modelled by a single lick of light. Among them nestle pears, apples, and perhaps a fig or quince, rendered with just enough specificity to be recognized and just enough stylization to remain decorative units within the pattern. The fruit is not arranged as a still life set on a table but gathered against a living body, so the sensations of touch and weight become part of the symbolism. Abundance is something felt, not merely seen.

Sensuality and Restraint

Mucha is often praised for making sensuality elegant, and “Fruit” is a prime example. The bare back and turned glance invite desire, while the armful of grapes offers ripe metaphor. Yet nothing is prurient. The figure is neither coy nor passive; she is occupied with her harvest, fully at ease with being looked at yet not defined by that gaze. The sensual appeal is inseparable from the tactile truth of the scene—the slip of skin against fruit, the softness of hair against petals, the cool weight of metal armlets on warm flesh. Pleasure here is not spectacle but texture.

Space and Scale

The space is intentionally shallow. Background and figure are separated mostly by the halo of the arch and the thickness of the contour, keeping the eye at the surface. This compressed space is typical of Japanese woodblock prints, which influenced Mucha and many of his contemporaries. The lack of deep recession keeps attention on the rhythm of shapes and on the decorative harmony between figure and frame. Scale is generous: the heroine is nearly life-size within the panel, giving the image the presence of a portrait while preserving its allegorical distance.

Printing Craft and Collaboration

F. Champenois’s workshop realized these designs using multiple lithographic stones, each for a distinct ink. The challenge was to maintain the crispness of contour while laying large, even fields of color that would not cloud the paper or misregister across runs. Mucha designed with printers in mind. He used the paper’s white for the brightest notes, planned gradients that could be accomplished in two or three passes rather than many, and concentrated his most intricate linework in areas where the greasy lithographic crayon could hold detail without filling in. The longevity of surviving impressions attests to the success of that craft. Even when slightly sun-faded, the panels retain their melodic clarity.

The Allegory of Autumn

Although “Fruit” bears no explicit label, its theme aligns with autumn. The heroine’s hair tones mimic late-summer fields; the fruit suggests harvest festivals; the palette possesses the mellow heat of September afternoon. Mucha liked to encode the seasons in this indirect way, allowing a single panel to carry both literal and metaphorical associations. As an emblem of autumn, “Fruit” avoids melancholy. There is no chill wind or falling leaf; there is only the joy of ripeness. In a domestic space, the panel would have acted like a hearth image, warming winter rooms with remembered sun.

Relation to Companion Panels

Seen beside “Flower,” the sister panel from the same period, “Fruit” offers a deliberate contrast. “Flower” is frontal, devout, and perfumed; “Fruit” is turned, tactile, and flavorful. Where “Flower” crowns the figure with white lilies and laces the sleeves with embroidery, “Fruit” bares the back and fills the arms with grapes. The two together describe a spectrum of femininity in Mucha’s imagination: contemplative grace on one side, sensuous abundance on the other, joined by the same architecture of arch, spandrels, and calligraphic line.

The Viewer’s Path

Mucha engineers a viewing rhythm that mimics the tasting of fruit. The gaze first lands on the face, drawn by the direct, almost amused eyes. It slides to the floral crown, then pours down through hair and shoulder to the swelling clusters of grapes. From there it loops along the curve of the arm, touches the glinting spirals, and returns to the face by a path of stems and ringlets. This loop takes the eye back and forth between appetite and recognition, between the material and the ideal, which is exactly the tension that keeps the panel endlessly lookable.

Cultural Meanings and Modern Appeal

“Fruit” reflects Belle Époque optimism: an urban society reveling in modern printing and electric light while nostalgic for classical abundance and natural rhythm. It maps desire onto an ethical aesthetic in which beauty is not a guilty pleasure but a civilizing force present in interiors, menus, and manners. Its appeal today rests on similar ground. The panel offers a counterweight to digital glare and photographic literalism, reminding viewers how a few curving lines and well-chosen colors can generate a whole climate of feeling. Designers still borrow its integrated framing, its floral-hair hybrids, and its strategy of making ornament do narrative work.

Conclusion

“Fruit” is Art Nouveau at full ripeness. A woman turns with an armful of grapes, her hair and flowers alive with the same energy that fills the vines. The palette glows with late-summer warmth; the line sings in phrases that make skin, silk, metal, and pulp converse; the architecture of the panel creates a sanctuary where abundance is both offered and enjoyed. In the modest format of a domestic lithograph, Alphonse Mucha achieves the old ambition of allegory without solemnity. He makes a season visible, a taste tangible, and a room more hospitable to pleasure. To stand before the image is to feel the sweet weight of harvest rest, if only for a moment, in one’s own arms.