Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction: A Grand Equestrian Portrait Reimagined

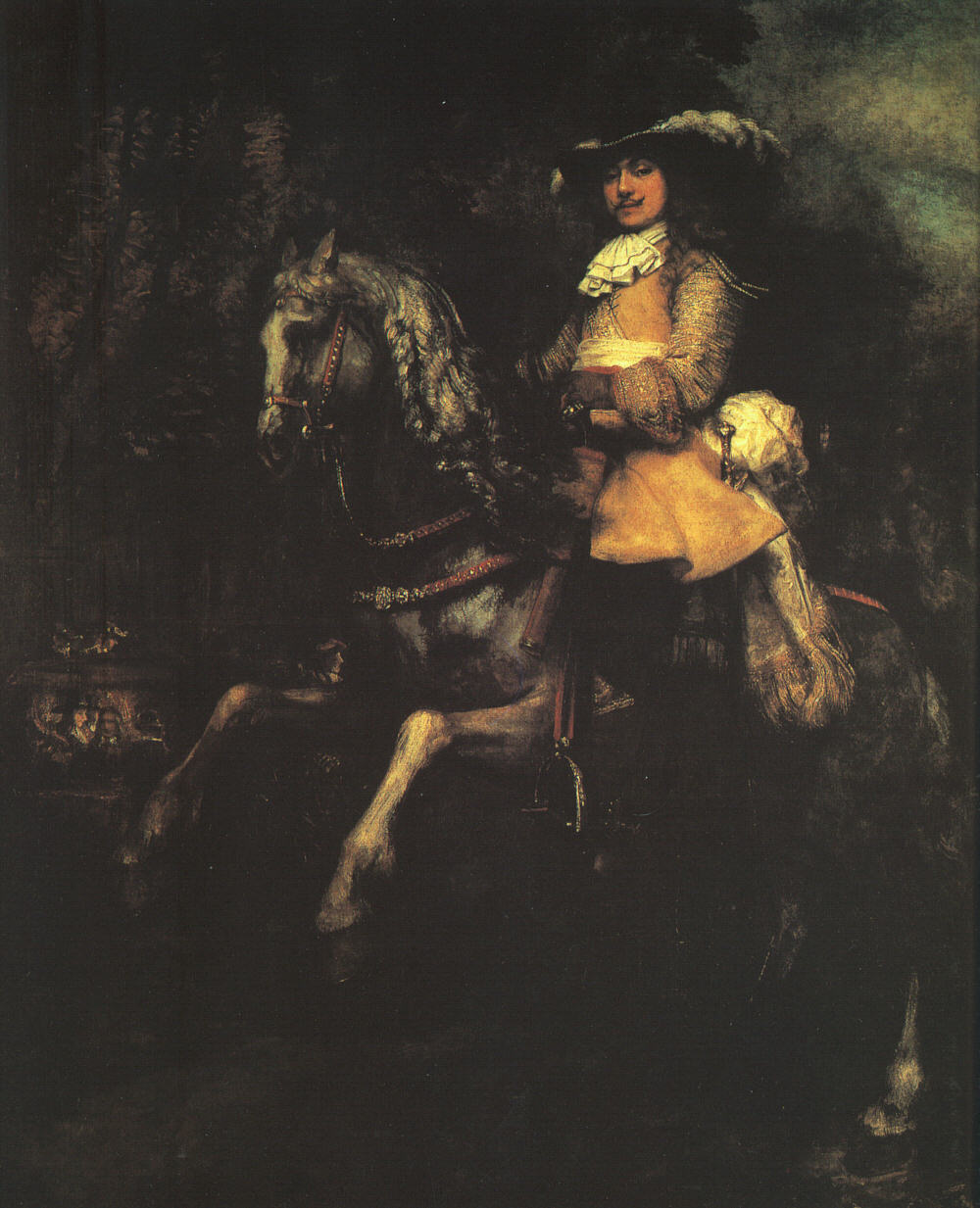

“Frederick Rihel on Horseback” (1663) occupies a singular place in Rembrandt’s late oeuvre. It is one of the few fully realized equestrian portraits from the Dutch Golden Age and the only one by Rembrandt with such dramatic, life-scale ambition. The painting presents the wealthy merchant and civic figure Frederick Rihel astride a spirited grey horse. With a plume-topped hat, metallic sleeve, white sash, and richly ornamented tack, Rihel rides forward from a shadowed grove into a wedge of light. Yet, unlike courtly equestrian images by Rubens or Van Dyck, Rembrandt’s vision tempers display with psychological nuance. The result is an image that reads as both public monument and private character study, a portrait that portrays status while also revealing temperament.

The Late Style And Its Human Gravitas

By 1663, Rembrandt had weathered personal losses, bankruptcy, and the shifting tastes of Amsterdam patrons. His technique had become freer and more tactile, with paint describing not only visible surfaces but the feeling of things—metal that catches light like quicksilver, horsehair that seems to breathe, skin that opens to the air. In this work the late style becomes a vehicle for grandeur. The paint is thick and broken in the horse’s mane and trappings, scumbled and airy in the clouded background, and buttery over the sitter’s face and hands. This material richness is not a flourish; it is a way of making presence tangible, as though the horse’s breath and Rihel’s pulse have been caught in oil.

Composition: A Diagonal Of Power And Control

Rembrandt builds the composition on a strong diagonal that runs from the horse’s lifted foreleg through Rihel’s torso to the plume of his hat. The animal is captured in passage, one hoof raised, head turned, nostrils lightly flared. This dynamic line drives us toward the rider’s upper body where face and hat concentrate the light. Opposing diagonals stabilize the figure: the sword hilt, the white sash, the angle of the saddle, and the fall of the horse’s reins provide cross rhythms that keep motion under command. The background’s dark mass of foliage forms an embracing arc that frames the pair and pushes them forward, turning a moment on a ride into a staged revelation.

The Horse As Partner And Mirror

Equestrian portraits traditionally make the horse a pedestal for the rider’s glory. Rembrandt instead grants the animal agency. The grey is alert yet responsive, its eye glinting, mouth softly parted, veins and musculature suggested with broken strokes that carry energy without pedantry. The horse’s ornate bridle and breast collar sparkle with dabs of high impasto that register like real metal. Most striking is the creature’s psychology: it neither lunges nor cowers; it participates. The animal’s poised movement parallels a rider whose confidence is real but not flamboyant. In this partnership Rembrandt finds character—discipline without rigidity, vigor without noise.

Frederick Rihel: Public Identity And Private Introspection

Costume tells us who Rihel is in the world: a prosperous Amsterdammer with connections, wealth, and taste. The metallic sleeves, the crisp fall of lace, and the pale sash across the belly declare rank, while the broad hat and plume add theatrical height. Yet the face complicates the pageant. Rembrandt paints Rihel looking slightly down and out toward the viewer, with a hint of reserve behind the mustache and close-set eyes. It is not the triumphant stare of a conqueror but the measuring gaze of a man accustomed to the brisk negotiations of commerce and civic duty. The hand at the reins is calm; the posture upright but not stiff. We sense a man attuned to appearances, aware of his position, but ultimately defined by composure rather than swagger.

Chiaroscuro And The Theater Of Arrival

Rembrandt’s light enters from the right, acting like a stage lamp that reveals the rider as he emerges from forest shadow. The horse’s silvery head and Rihel’s chest receive the brightest accents; the background remains a deep register of greens and browns that drinks light instead of reflecting it. This chiaroscuro dramatizes motion—coming out, coming forward—while also creating a psychological envelope. The darkness behind reads as history and nature; the light is the social world where identity is seen and judged. Rembrandt’s manipulation of value thus transforms a ride into a narrative of presentation, an allegory of stepping into the public eye.

Surface, Touch, And The Craft Of Presence

The painting’s tactile variety is extraordinary. The horse’s mane is laid in with vigorous, almost abstract strokes that curl and separate like living hair. The lace at Rihel’s throat is a network of delicate highlights dragged over a darker base, producing a convincing illusion of filigree without labored description. The leather saddle and scabbard carry broader, warmer strokes that suggest wear and suppleness. Metallic sleeves catch the light with stippled touches that make the surface shimmer rather than shine flatly. Everywhere, Rembrandt’s brush leaves evidence of contact, as if to remind us that vision in painting is always a form of touch.

The Vocabulary Of Costume And Meaning

Every item on Rihel’s body participates in meaning. The white sash operates as a luminous belt that both secures the rider’s center and vectors light toward the face. The gauntleted hand, painted with dense, warm tones, speaks of action and protection, suitable for a gentleman who rides prepared. The plume is not frivolous; placed against a darker sky, it punctuates the upward thrust of the diagonal and amplifies height. Even the small knot of gold at the bridle, just catching light, acts as a hinge between animal and human, wealth and will.

The Landscape As Dramatic Foil

The background is not an inventory of trees and sky; it is a tone poem. Rembrandt uses broad, murky glazes to set a world into which the equestrian pair ride as a singular event. The vertical shadow at left acts like a stage wing, cropping the space so that the rider appears more suddenly. Flecks of light in the upper right imply a clearing or break in the canopy. This abbreviated landscape contributes to the painting’s narrative rhythm: from the dark perimeter to the bright center, from inwardness to public revelation.

Movement Captured, Not Frozen

Action paintings often freeze a peak moment. Rembrandt chooses a mid-beat—the horse’s foreleg lifted, the rider’s torso gently twisting—which suggests continuity rather than a shuttered pose. We feel what happened just prior and anticipate the next step. This temporal openness contributes to the painting’s liveliness. Rihel is not just depicted; he is arriving. The state portrait becomes cinematic, a moving picture achieved without blur, using instead the choreography of diagonals and the breath of brushwork.

Comparison With Courtly Equestrian Traditions

If we compare this work with equestrian masterpieces by Titian, Rubens, or Velázquez, Rembrandt’s divergence becomes clear. Those courtly images typically isolate ruler and horse against a grand setting, often with banners, attendants, or military vistas. Splendor confirms political power. Rembrandt, painting for a mercantile republic, introduces intimacy and shadow. Rihel is noble in bearing but not imperial; his authority is civic, earned more from prudence than from divine right. The painting thus translates a royal format into a Dutch register, keeping the thrill of equestrian spectacle while aligning it with republican virtues—competence, restraint, and individual responsibility.

Psychological Resonance Through Asymmetry

A key to the painting’s emotional depth lies in its carefully judged asymmetries. The horse’s head turns one way while the rider’s gaze, under the brim, angles slightly another. The mane is wild on the far side, subdued on the near. The plume tilts with a jaunty logic that counterbalances the heavy sash. These small departures from symmetry keep the image alive and convey the basic human condition of managing many forces at once—animal power, social expectation, self-possession—without perfect alignment. The viewer recognizes this balancing act and reads it as character.

The Palette: Warm Earths And Electric Silvers

Rembrandt organizes color around warm browns and golds offset by the cool silver of the horse and a few notes of muted red in the trappings. The limited palette intensifies the play of light and the painting’s mood of twilight emergence. The warm passages bind rider and mount into a single unit, while the cool greys and whites articulate key forms—the horse’s blaze, the lace, the sash, the highlights on the bridle—that guide the eye. Subtle greens in the foliage modulate the darkness rather than compete with the central figures.

The Face As Anchor

Amid this whirl of textures and diagonals, the face remains calm. Rembrandt focuses attention here with tighter handling and a measured half-smile that holds meaning in reserve. The flesh is built with warm, slightly ruddy tones that color the cheeks and the nose, while minute touches around the eyes create the sensation of moisture and watchfulness. The face ties the painting’s public narrative to a private center, convincing us that the man before us knows both how he looks and who he is.

Symbolic Readings Without Allegory

Rembrandt avoids overt allegorical props, yet the painting carries symbolic weight. The controlled horse can stand for disciplined energy, a desirable quality in a civic leader or successful merchant. The move from shadow to light can signify reputation entering its culmination. The gleaming bridle and sword hilt evoke stewardship and readiness rather than aggression. By letting symbols arise from composition and gesture rather than from added emblems, Rembrandt keeps the picture grounded and credible.

Studio Strategy And The Illusion Of Spontaneity

Close looking suggests that Rembrandt may have developed the horse and rider in stages, building the animal’s body with sweeping passages before refining tack and anatomy, then settling the rider in with a different, more deliberate tempo. The painting’s unity relies on later passages that stitch the two together—shared highlights, connecting shadows, and overlaying glazes that harmonize temperatures. This layered method gives the finished work its hallmark combination of boldness and cohesion: the scene feels instantaneous while bearing the traces of careful orchestration.

The Viewer’s Position And The Social Contract

We stand slightly below the rider’s eye level, more spectator than participant. Yet the proximity of the horse’s near leg and the near stirrup brings us almost into the zone of risk. It is as if we have stepped aside to let Rihel pass, and in that split second he turns toward us. The perspective enacts a social contract—respect from below, acknowledgment from above—and the painting enforces it with courtesy rather than domination.

The Echo Of Sound And Atmosphere

Even though the image is still, Rembrandt makes room for implied sound. The jangling metal at the bridle, the soft thud of hooves, the rasp of leather, and the whisper of the plume against air all seem latent in the brushwork. The porous darkness of the trees absorbs these imagined noises, while the lighter area to the right—where the world opens—feels acoustically brighter. Few painters can make atmosphere so audible.

Legacy, Rarity, And Modern Appeal

As a late and rare equestrian portrait from Rembrandt, “Frederick Rihel on Horseback” prefigures modern expectations about portraits that must balance glamour with authenticity. Its audacity of format set against an introspective face resonates with contemporary viewers who distrust pure display but still respond to ceremony when it is earned. The painting also showcases Rembrandt’s gift for giving equal dignity to man and animal, letting the horse be more than furniture—something later artists from Géricault to Degas would explore with passion.

What The Painting Teaches About Power

Power here is not brute force or hereditary privilege; it is the ability to master movement, guide strength, and emerge into the light without losing composure. The reins lie comfortably in the hand; the horse advances but does not rear; the rider looks, acknowledges, and continues. Rembrandt thus converts a traditionally martial format into a civic ethic. It proposes that leadership is a matter of balance: between public and private, display and discretion, vigor and judgment.

Conclusion: Ceremony With A Human Pulse

“Frederick Rihel on Horseback” is ceremony with a heartbeat. Through chiaroscuro, diagonal structure, tactile paint, and psychological restraint, Rembrandt transforms a display of wealth into an encounter with presence. The rider advances from the wooded dark into the world’s regard, not to overwhelm but to be recognized. Horse and human move as one, an emblem not of domination but of practiced harmony. The painting stands as a rare and powerful synthesis—pageantry infused with candor, spectacle secured by empathy, and late style turned toward a timeless question: how should a person be seen when he steps into the light?