Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context of 1910

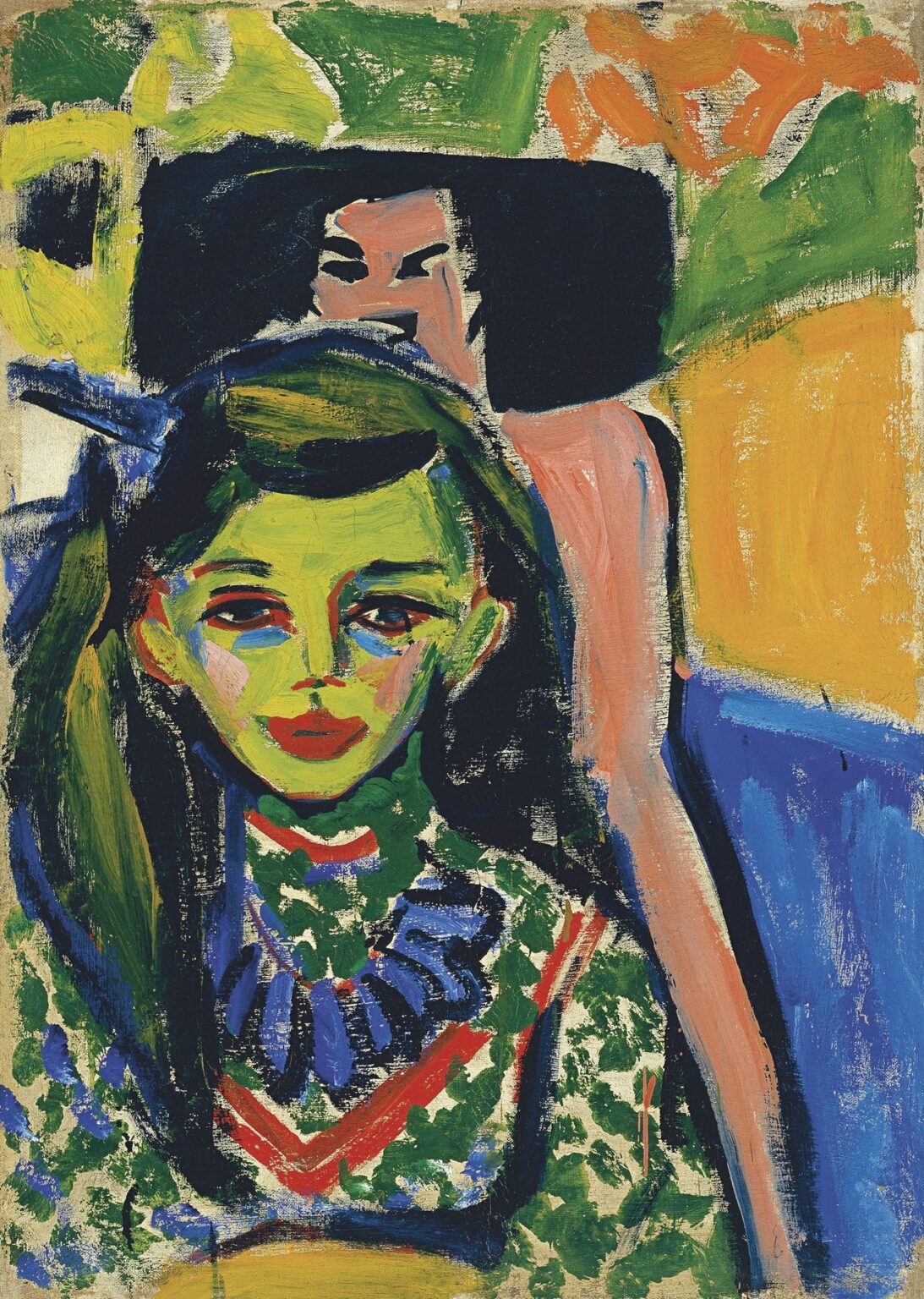

In 1910, Europe teetered on the edge of radical transformation. The serenity of the Belle Époque clashed with rapid industrialization, social unrest, and mounting tensions that would culminate in the First World War. In Germany, art academies still upheld conservative standards, yet a younger generation of painters sought fresh means of expression. In Dresden, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and his peers would soon form Die Brücke (The Bridge), a collective determined to reject academic mimicry in favor of raw emotion and unfiltered experience. Fränzi in front of Carved Chair, painted in the spring of 1910, marks one of Kirchner’s earliest strides into this new territory, fusing traditional figurative portraiture with the daring color and gestural energy that would come to define German Expressionism.

Kirchner’s Die Brücke Era

Kirchner co-founded Die Brücke in 1905 with Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Drawing inspiration from Post-Impressionism, folk art, and non-Western carving traditions, they sought to forge an art unmediated by rational academic constraint. By 1910, Kirchner had embraced the group’s ethos: painting directly from life, privileging spontaneity, and forging a visual language that fused line and color into a single emotive force. Fränzi in front of Carved Chair emerges at this critical juncture when Kirchner still observed representational forms but transposed them through an irrepressible personal sensibility—a balancing act between fidelity to his sitter and fidelity to his own inner vision.

The Model: Fränzi Fehrmann

“Fränzi” refers to Franziska Fehrmann, a young working-class girl from Kirchner’s Dresden neighborhood who became his frequent model between 1908 and 1911. Unlike the idealized nudes of academic tradition, Fränzi embodied an unvarnished vitality: a child shaped by everyday life, whose energy and candid presence captivated Kirchner. In this portrait, her wide-eyed gaze and poised stillness convey both youthful curiosity and an uncanny psychological depth. Kirchner’s repeated engagement with Fränzi across multiple canvases testifies to his desire to capture authentic, unidealized humanity—a fundamental tenet of Die Brücke’s vision.

Symbolism of the Carved Chair

The chair behind Fränzi is not a neutral prop but a dynamic participant in the composition. Its ornate back—likely influenced by African and Oceanic sculpture admired by Die Brücke artists—rises like a throne, framing her head and suggesting potential roles of authority and ritual. This juxtaposition of child and carved furniture underscores tensions between innocence and cultural legacy, the organic and the man-made. By placing Fränzi before this carved support, Kirchner dialogues with primitivist impulses: he elevates folk motifs into his modernist lexicon, using them to amplify his sitter’s expressive resonance.

Composition and Spatial Arrangement

Kirchner arranges Fränzi in front of Carved Chair within a tightly bounded space, emphasizing the sitter’s proximity to both viewer and chair. Fränzi’s head aligns centrally, while her shoulders and arms form subtle diagonals that echo the chair’s upward sweep. Sharp contrasts between the figure’s vertical posture and the chair’s undulating contours create rhythmic tension. In cropping the canvas close to her torso, Kirchner removes extraneous environment, compelling viewers to engage directly with Fränzi’s presence and the carved structure behind her. This compositional compression heightens psychological intensity, a hallmark that would mature in later Die Brücke portraiture.

Color Palette and Emotional Tone

Here Kirchner employs a palette both restrained and daring. Fränzi’s flesh merges pale peach with hints of pink and lavender, outlined in ebony strokes that define facial features and contours. Her dark garment recedes into a backdrop of deep ultramarine and viridian, while the chair’s carved elements appear in warmer ochres and russet accents. These limited yet contrasting hues generate emotional vibrancy: the warmth of her skin emerges more luminous against cool shadows, while the chair’s earth tones ground the composition. The result is a portrait that feels both intimate and charged, as if color itself contributes to the sitter’s psychological voice.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Kirchner’s handling of paint in this canvas combines broad, flat fields with decisive, linear gestures. The sitter’s hair and the chair’s elaborate carvings reveal quick, energetic strokes that preserve the dynamism of the artist’s hand. In contrast, the sitter’s face is rendered with softer transitions, allowing her expression to register subtle nuance. Thin layers in some areas permit the raw canvas ground to peek through, adding a luminous depth beneath opaque passages. This interplay of revealing and concealing surfaces mirrors the painter’s dual aim: to reveal Fränzi’s inner life while acknowledging the material truth of paint. The tactile presence of the brush thus becomes a metaphor for the portrait’s emotional immediacy.

Treatment of the Human Figure

Unlike academic portraiture’s emphasis on anatomical exactitude, Kirchner abstracts Fränzi’s features into essential planes and rhythmic lines. Her eyes become horizontal slashes, her mouth a simple curve. Such reduction does not impoverish expressiveness; rather, it intensifies it. By stripping away detail, Kirchner evokes universal human qualities—innocence, attentiveness, reserve—while preserving the sitter’s distinct character through compositional context and color accents. The figure’s solidity stems not from muscular modeling but from the confidence of line and tonal contrast, hallmark traits of early Expressionist figuration.

Interaction of Figure and Furnishing

Throughout the composition, figure and carved chair resonate with one another. Fränzi’s raised shoulder aligns with the chairback’s crest, forging a continuous visual arc. The angularity of her sleeve echoes cut-out patterns in the wood, while the linear flow of her hair parallels the chair’s carved motifs. This formal dialogue underscores the painting’s thematic interplay between human and crafted forms, hinting at tensions between tradition and personal identity. Kirchner thus transforms a simple portrait into an exploration of how individuals inhabit, shape, and are shaped by their cultural surroundings.

Psychological Depth and Expression

Expressionism’s core pursuit lay in externalizing inner emotion. Fränzi in front of Carved Chair embodies this through the sitter’s arresting gaze: her slightly parted lips and steady, inscrutable eyes convey both youthful vulnerability and quiet resilience. The carved chair’s looming presence amplifies this psychological charge, bestowing a sense of ceremony upon an otherwise everyday figure. Kirchner’s composition invites viewers to sense Fränzi’s interior world: her direct gaze challenges us, demanding recognition of her dignity and complexity. In this way, the painting transcends portraiture to become an empathic encounter between artist, sitter, and spectator.

Technical Materials and Artistic Process

Executed in oil on canvas roughly 74 by 50 centimeters, Fränzi in front of Carved Chair demonstrates Kirchner’s resourceful engagement with readily available materials. X-ray analysis reveals a single ground layer upon which he built form with minimal preparatory sketching—attesting to his commitment to speed and spontaneity. Pigments include earth reds for her flesh, synthetic ultramarine for shadows, and chromium oxide greens in select highlights. Slight craquelure in thicker impasto indicates natural aging, yet overall the work’s surface retains vivid color—evidence of Kirchner’s material savvy and the inherent stability of his chosen pigments.

Provenance and Exhibition History

Soon after its creation, Fränzi in front of Carved Chair entered Die Brücke’s inaugural exhibitions in Dresden, where its candid subject and daring palette provoked both admiration and scandal. Critics decried its “unfinished” brushwork even as others hailed its emotional candor. Acquired by a private collector sympathetic to the avant-garde, the painting avoided confiscation during the Nazi purges of “degenerate art” in the 1930s. Post-war, it emerged in major retrospectives of Kirchner’s oeuvre at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin and the Kirchner Museum in Davos, where it secured its status as a foundational Expressionist portrait.

Critical Reception and Scholarly Interpretation

Art historians view Fränzi in front of Carved Chair as a pivotal early work, bridging Kirchner’s academic training and his full Expressionist breakthrough. Critics note its formal experiments—flattened space, minimal modeling, emotive color—as harbingers of his later street scenes and nudes. Psychoanalytic readings emphasize the carved chair’s framing of Fränzi’s psyche, suggesting that the artwork mediates self-expression amid cultural strictures. Feminist scholars have also mined the portrait, examining how Kirchner’s depiction of a working-class girl reflects both empathy and the power dynamics inherent in artist-model relationships.

Influence on Later Artists and Movements

The portrait’s fusion of gestural line and flat color fields influenced subsequent German Expressionists, including Otto Dix and Max Beckmann, who likewise foregrounded psychological immediacy over academic form. Beyond Expressionism, the canvas’s emphasis on paint’s material presence resonated with mid-century Abstract Expressionists exploring the body’s impact on surface—Jackson Pollock’s action painting, for example, echoes Kirchner’s early valorization of process. Contemporary figurative painters continue to reference Kirchner’s approach to portraiture, especially his skill in balancing formal abstraction with empathic intensity.

Personal Engagement and Viewer Reflection

Encountering Fränzi in front of Carved Chair today is to confront the enduring power of early Expressionism. One senses the painter’s urgency in every brushstroke, the sitter’s humanity in her direct gaze, and the carved chair’s symbolic weight in its bold silhouette. The painting rewards sustained attention: as one’s eyes trace the interplay of line, color, and form, emotional undercurrents emerge—curiosity, protection, latent tension. Kirchner’s canvas becomes a mirror, inviting viewers to reflect on their own encounters with cultural tradition, personal identity, and the promises and perils of unfettered expression.