Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

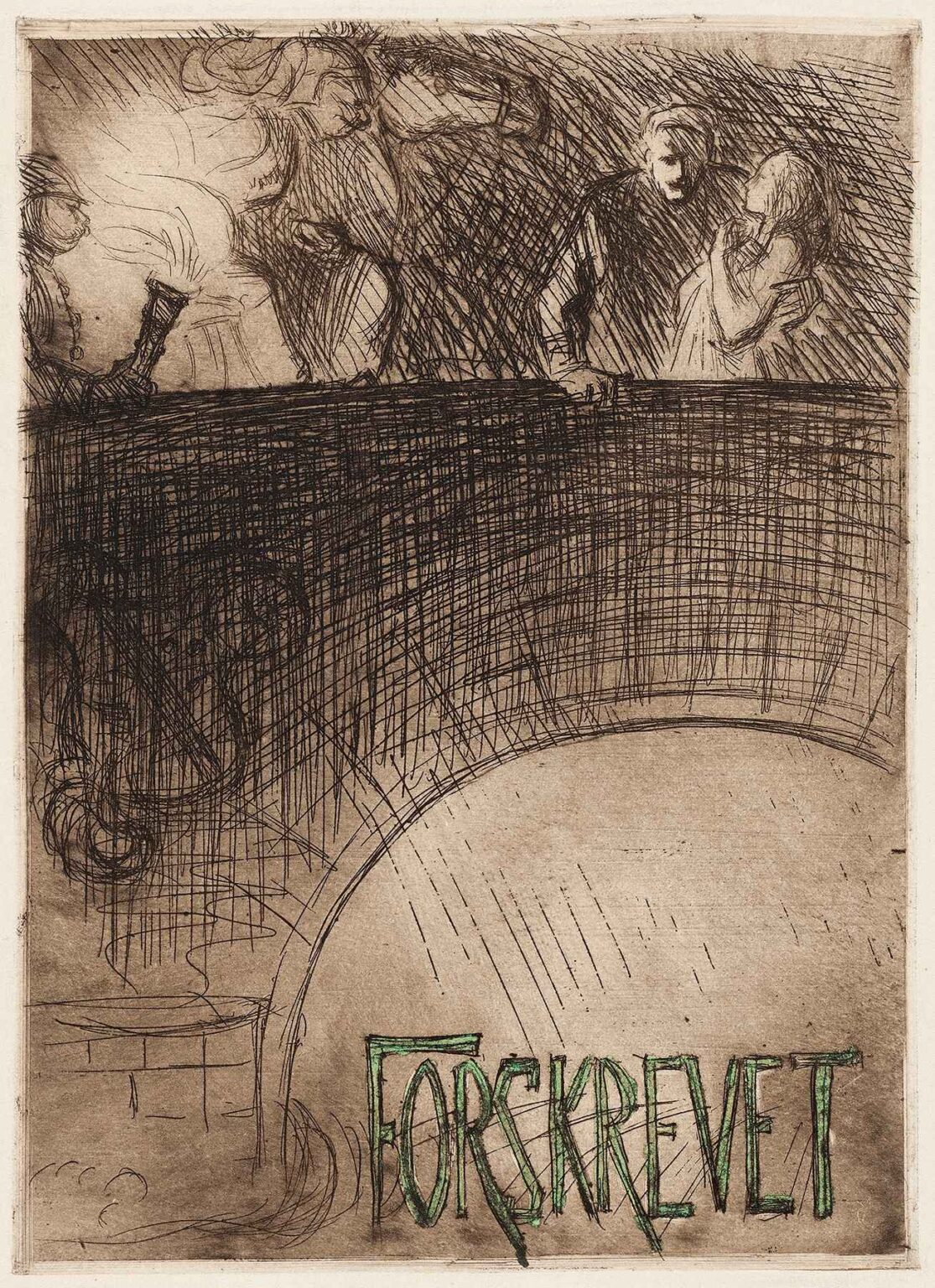

Magnus Enckell’s 1901 etching Forskrevet stands as a striking testament to the Finnish Symbolist’s ability to conjure a haunting atmosphere through spare linear gestures and poignant imagery. Poised between painting and printmaking, Enckell’s work from this period reveals his fascination with themes of existential alienation, spiritual longing, and the boundary between life and death. In Forskrevet, a sparse architectural motif—a broad arch—dominates the lower half of the composition, while above it a small group of figures emerges from cross-hatched darkness. The title, which roughly translates as “written off” or “discarded,” underscores a sense of abandonment or finality. Over the course of this in-depth analysis, we will delve into Enckell’s biographical and artistic context, examine the work’s compositional structure and technical execution, explore its symbolic resonances, and situate Forskrevet within the artist’s broader Symbolist project and the turn-of-the-century European avant-garde.

Magnus Enckell and the Turn of the Century Symbolist Milieu

By the dawn of the 20th century, Magnus Enckell (1870–1925) had established himself as one of Finland’s preeminent Symbolist painters. Educated in Helsinki and later in Paris, Enckell absorbed the currents of French, Belgian, and Finnish Symbolism. His earliest mature works—softly lit, often portrait-like paintings of ethereal figures—revealed an abiding interest in mood, introspection, and color’s emotive power. Yet just as the Symbolist movement in painting was gravitating toward decorative flatness and dream-like color palettes, Enckell turned increasingly to the medium of printmaking, drawn by its potential for stark contrasts, intricate line work, and expressive textures.

Forskrevet appeared in 1901, a pivotal moment when Enckell was experimenting with etching alongside fellow Finnish Symbolists like Hugo Simberg. The new medium allowed him to translate his interest in twilight landscapes and solitary figures into crisp black-and-white imagery that felt both intimate and universal. In this milieu, prints functioned as vehicles for disseminating elusive, even uneasy, visions of the human condition: mortality, spiritual exile, and the ever-lurking presence of otherworldly forces.

Title and Thematic Resonance

The Swedish-language title “Forskrevet” carries a double valence in Finnish Swedish dialect. On one level it means “written off” or “discarded,” suggesting abandonment or dismissal. On another, it evokes the idea of an official inscription or edict—an irrevocable pronouncement. Enckell’s choice of this ambiguous term primes the viewer to sense both an act of forsaking and the weight of inescapable fate. Against the backdrop of Nordic modernity—rapid industrialization, social upheaval, and the search for national identity—“written off” might apply to individuals who felt out of sync with the march of progress or marginalized by emerging bourgeois norms. In this sense, Forskrevet can be read as a symbolist lament for those whom the new century seemed poised to leave behind.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Visually, Forskrevet divides into two distinct registers. The lower half is dominated by the sweep of a great arch, depicted through dense cross-hatching that plunges its underside into deep shadow. This archway suggests an architectural threshold—perhaps the mouth of a tunnel, the underside of a bridge, or the vaulted ceiling of a crypt. Its semicircular curve anchors the composition and evokes the notion of a gateway between realms.

Above the arch, a stark horizontal line of demarcation leads the eye to a cluster of four figures rendered in looser, sketch-like strokes. They appear to press forward against an abyss of shadow, as though caught at the edge of an unseen precipice. One figure grasps the arch’s rim, another comforts a companion, their postures conveying anxiety and solidarity. The void beneath them remains ominously blank—in principle, an open space into which they might tumble. This spatial tension between the solid arch and the abyssal void heightens the image’s psychological charge: we sense an imminent choice or irreversible crossing.

Use of Line and Etching Technique

Enckell’s mastery of the burin and etching needle is on full display. The arch’s underside features dense, regular cross-hatching: thousands of intersecting lines that coalesce into a velvety black. These disciplined strokes contrast with the more spontaneous, calligraphic marks describing the figures above. By varying his line weight—from the thinnest scratch to the firmest grooved incision—Enckell sculpts both form and atmosphere.

The figures themselves emerge from shadow through lighter, more gestural hatchings. Some outlines remain intentionally incomplete, allowing the surrounding darkness to insinuate itself. This economy of line—wherein a few deft marks can conjure a hand clasping an arm or a head bowed in despair—reflects the Symbolist credo that suggestion, not explicit depiction, best evokes the realm of the spirit.

Symbolism and Mood

As with many Symbolist works, Forskrevet resists a single, definitive interpretation. The arch may symbolize the threshold between life and death, the conscious and unconscious, the seen and unseen. The figures’ ambiguous identities—ghostly, almost spectral—hint at souls contemplating passage. Their clustered grouping implies mutual support in the face of existential dread. One might see a dying family or group of pilgrims poised before the “written-off” fate that awaits them beyond the arch.

At the same time, the void beneath can stand for modernity’s abyss—industrial alienation or the spiritual emptiness of secular society. In this reading, Forskrevet laments those “written off” by progress: workers discarded by mechanization, dreamers ostracized by rationality, or individuals adrift in the impersonal currents of urban life. Enckell’s source of inspiration may have included the darker Romantic imagery of writers like Edgar Allan Poe and the medieval allegories of Hieronymus Bosch, lightly filtered through fin-de-siècle finlandisms.

Tonal Range and Paper as Medium

Etching as a medium offers a limited tonal range—black ink on pale paper—but Enckell exploits subtle gradations by controlling plate tone. The arch’s upper surface demonstrates mid-tone areas where fewer hatchings let the paper glow through, suggesting a milder light source. In contrast, the arch’s underside and the background sky around the figures approach near-black density. By allowing the untouched paper to show through in the void below, Enckell creates a third, luminous plane: a searing blankness that reads almost like starlight or a spiritual realm beyond gravity.

The choice of paper also affects the work’s mood. The slightly warm, off-white tone of the paper complements the sepia-like ink, lending the print an antique air—as though it emerged from an earlier century or an imagined chronicle. This aged aesthetic enhances the timeless quality of the scene and reinforces its Symbolist desire to transcend the immediate present.

Figures in the Arcane: Gestures and Relationships

Examining the quartet of figures above the arch reveals a micro-drama of emotional nuance. One figure pries open the arch’s rim, perhaps in hope of seeing what lies beyond; another seems to lean heavily on a companion, posture slumped in resignation. A third figure clasps their hands, as if in prayer or dread, while the fourth stands slightly apart, gaze fixed into the void. These gestures evoke fear, curiosity, solidarity, and isolation in equal measure.

Enckell’s rendering deliberately blurs individual identities; the figures lack distinguishing facial features or attire. This anonymity transforms them into archetypes—shadows of humanity at large. Viewers are invited to project their own fears and hopes onto these figures, identifying with their precarious stance at the threshold of an unknown abyss.

Comparing Forskrevet to Enckell’s Painted Symbolist Works

While best known today for his luminous, pastel-toned paintings of ethereal adolescents and angels, Enckell’s printmaking output reveals a darker, more restless side of his imagination. In paintings such as Youth and the Maiden (1894) and Spring Mood (1900), he luxuriates in soft color transitions, harmonious compositions, and gentle allegories of innocence and renewal. Forskrevet, by contrast, dispenses with color altogether and plunges headlong into the chiaroscuro of existential dread.

This polarity underscores the breadth of Enckell’s Symbolist vision. On one hand, he celebrates the soul’s beauty and aspiration; on the other, he confronts its vulnerability and mortality. Both impulses—uplift and disquiet—coexist in his oeuvre, making him a uniquely complex figure within Nordic art at the turn of the century.

Technical Process: From Plate to Print

Creating an etching involves coating a metal plate with acid-resistant ground, incising lines through that ground with a needle, then bathing the plate in acid to bite into the exposed metal. Enckell likely began with rough sketches in his studio, then transferred key compositional lines onto the plate using drypoint. The final hatching required steady hand-eye coordination and precise timing—too brief an acid bite yields shallow, weak lines; too long produces overly dark, bloated marks.

Once the plate was inked and wiped, paper would be laid atop it and run through a high-pressure press, transferring the ink from the plate’s recesses to the sheet. Each impression can vary slightly, giving early proofs a distinctiveness prized by collectors. Enckell’s surviving impressions of Forskrevet show subtle variation in tone and line crispness, suggesting he supervised multiple print runs and perhaps experimented with plate tone to refine the work’s expressive power.

Reception, Publication, and Legacy

Although Enckell’s prints never achieved the commercial visibility of his paintings, they circulated among fellow Symbolists and avant-garde journals. Forskrevet may have appeared in a limited edition portfolio or as an illustration accompanying poetry in Swedish-language cultural magazines based in Helsinki and Turku. Its stark vision resonated with audiences attuned to the darker undercurrents of modernity and the spiritual anxieties of the age.

In subsequent decades, art historians rediscovered Enckell’s prints as crucial counterpoints to his well-known canvases. Scholars emphasize how his etchings, including Forskrevet, anticipated Expressionist and Surrealist preoccupations with alienation and subconscious depths. Today, the work is recognized as one of the high points of Nordic printmaking at the fin de siècle, bridging nineteenth-century Romanticism and twentieth-century modernism.

Conclusion

Magnus Enckell’s Forskrevet (1901) remains a haunting meditation on thresholds—between life and death, light and shadow, hope and despair. Through a masterful interplay of line, tone, and symbolic ambiguity, Enckell conjures a scene at once intimate and universal: four faceless figures poised at the brink of an abyss, gazing into the unknown they have been “written off” to face. This etching encapsulates the dual thrust of Enckell’s Symbolism—its longing for transcendence and its unflinching confrontation with existential despair. As both a technical tour de force in the medium of etching and a profound statement on the human condition, Forskrevet secures its place as a landmark of Nordic modernist art and continues to captivate viewers more than a century after its creation.