Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context: The Dutch Bulb Fields and Van Gogh’s Early Career

In 1883, Vincent van Gogh was a young artist finding his voice amidst the flat landscapes of North Holland. Having left the coal‐mining district of Borinage and the somber interiors of Dutch peasant life, he spent the spring of that year in the village of Nieuw‐Amsterdam and later near the bulb fields around Haarlem and Lisse. These bulb fields—where millions of hyacinths, tulips, and daffodils were cultivated in neat, colorful rows—provided Van Gogh both subject matter and a chance to experiment with vivid color contrasts after years of earth‐toned restraint. “Flower Beds in Holland” was painted during one of his most formative periods, when he was mastering plein‐air techniques and laying groundwork for the bold palette that would later define his Arles and Saint‐Rémy masterpieces.

The Subject: Patterned Rows of Blooms

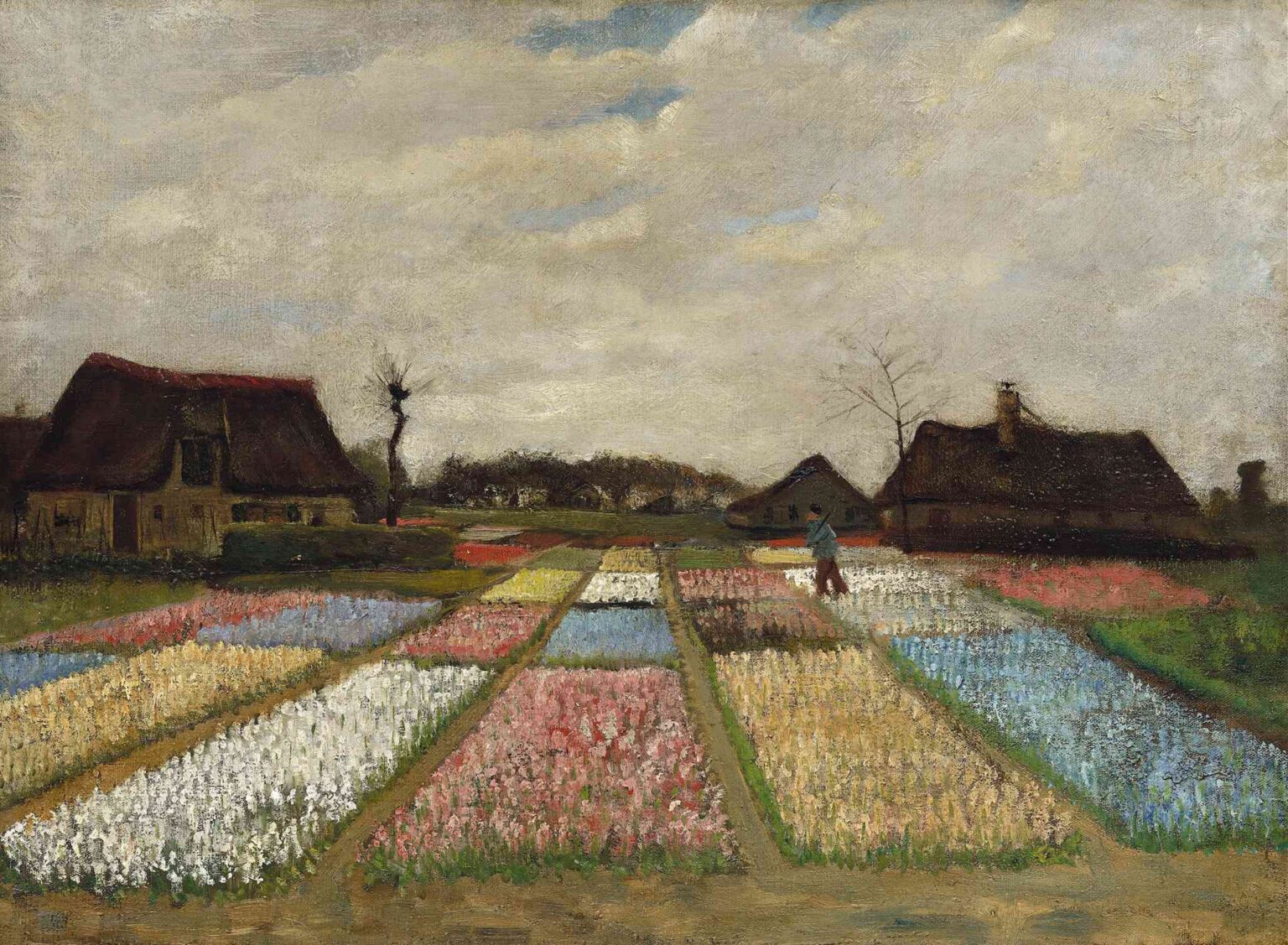

At first glance, “Flower Beds in Holland” presents a simple scene: rectangular plots of flowering bulbs, each bed bursting with a uniform hue. Yet Van Gogh’s interest lay less in botanical accuracy than in capturing the rhythm and geometry of cultivated land. The artist chose a vantage point close to the ground, allowing the flowerbeds to march toward the horizon in converging lines. Each rectangular bed—filled with white, pink, yellow, or pale blue blooms—becomes a color block, emphasizing the patterning of human agriculture within the expansive Dutch terrain. Beyond the beds, thatched farmhouses and wind‐scarred trees under a wide, brooding sky remind us that cultivation occurs within a larger, often harsh natural environment.

Composition: Geometry and Depth

Van Gogh structures the painting with a clear sense of depth and order. The foreground is dominated by the widest beds, their parallel edges aligned with the canvas margins, creating a strong visual axis. As the rows recede, Van Gogh subtly narrows their width and foreshortens their pattern, guiding the viewer’s eye toward the middle distance where a lone figure—a gardener or bulb planter—stands between the beds. The horizontal rooflines of low farm buildings counterbalance the verticality of leafless pollarded trees, while a faint horizon line separates land from sky. Although the composition is orderly, the loose handling of paint and slight irregularities in the bed edges introduce a human touch, reminding us that these fields are products of labor rather than mechanical precision.

Palette: Emerging Vividness within a Muted World

“Flower Beds in Holland” marks an important step in Van Gogh’s chromatic evolution. While his earliest works are dominated by umber and sienna, here he introduces more saturated pigments: soft pinks for hyacinths, pale yellows for narcissi, and cool blues for early tulips. Yet these bright colors are still tempered by gray‐green leaves and a sky of muted gray-blue. The ground between the beds is painted in ochre and green ochre, linking the colorful rows to the earth. This careful balance between vibrancy and restraint reflects Van Gogh’s transitional phase: he was experimenting with stronger color yet had not fully embraced the sunlit intensity that would characterize his later Provençal paintings.

Brushwork: From Controlled Strokes to Expressive Energy

In this early plein‐air work, Van Gogh’s brushwork combines deliberate, linear strokes in the flowerbeds with more fluid, sketchy touches in the sky and background foliage. His strokes in the rows are tight and directional, following the neat planting lines and emphasizing pattern. In contrast, the sky is built from broader, swirling strokes of white and gray, portending the dynamic impasto that would define his Arles landscapes. The contrast between controlled and spontaneous handling imbues the scene with both stability and life. Even in 1883, Van Gogh was exploring how variation in stroke length and direction could evoke differing textures—from rigid beds to restless clouds—laying the groundwork for his mature style.

Light, Atmosphere, and Seasonal Nuance

Painted in the cool, diffused light of a northern spring, “Flower Beds in Holland” conveys an air of quiet anticipation. The absence of strong shadows suggests an overcast sky, common in the bulb‐growing season when cold rains often linger. Van Gogh captures this atmospheric subtlety through his palette: grays in the sky blend into the muted greens of distant hedges, while the farmhouses’ thatch roofs carry soft brown tones that harmonize with the soil. This subdued light allows the delicate pastels of the flowerbeds to stand out without harsh contrast, reflecting Van Gogh’s sensitivity to seasonal conditions and his desire to record nature’s authentic color relationships.

Symbolism and Themes: Labor, Cultivation, and Transience

The bulb fields of Holland are sites of both beauty and industry. Each bed represents the fruits of painstaking human labor—planting, tending, and harvesting millions of bulbs for the commercial flower trade. By choosing this subject, Van Gogh nods to themes of cultivation and the human capacity to impose order on nature. Yet the transience of spring blooms, destined to be cut or wilt within weeks, also reminds viewers of impermanence. The lone gardener, shown at work among the beds, underscores the fleeting nature of both blossoms and human effort against the vast cyclical forces of seasons. In this sense, the painting becomes a meditation on creation and decay, a motif that would recur powerfully in Van Gogh’s later depictions of wheatfields and cypress groves.

Emotional Resonance: Solitude and Connection

“Flower Beds in Holland” conveys a quiet emotional tenor. The solitary figure working amid the geometric blooms suggests both the dignity and solitude of rural labor. Van Gogh’s choice to place the human form at a distance emphasizes the landscape’s primacy, yet also invites empathy: the worker is neither anonymous background nor heroic foreground but an integral part of the scene’s life. The orderly rows and muted light evoke a calm introspection, reflecting Van Gogh’s own shifting moods during a period of personal uncertainty. Through color and composition, he elicits from a seemingly mundane subject a subtle poignancy—a resonance between human toil and the silent growth of flowers.

Technical Insights and Materials

Scientific examination of Van Gogh’s early Dutch period works reveals a restrained palette centered on lead white, yellow ochre, green earth, umber, and emerging use of cobalt blue and madder lake. In “Flower Beds in Holland,” under-magnification shows a thin priming layer applied with a warm gray tone, allowing some warmth to seep through the cooler greens and blues. Infrared reflectography indicates minimal underdrawing, suggesting Van Gogh painted directly with brush, refining forms in situ. The paint layer is relatively thin with modest impasto, characteristic of his tentative early plein-air experiments. Conservation reports note that the canvas has remained structurally stable, with minimal craquelure and good adhesion of paint to ground.

Provenance and Early Exhibitions

After completing the painting, Van Gogh likely sent “Flower Beds in Holland” to his mother or sister Will in the family’s home in Nuenen. However, many of his Dutch works remained in the family’s possession until the 1920s, when collectors and museums began to recognize his brilliance. “Flower Beds in Holland” entered public view only decades after his death, first appearing in a retrospective exhibition in Amsterdam in 1925. By mid-century it had found its way into a major European museum collection, where it has since featured in exhibitions tracing Van Gogh’s developmental phases—demonstrating how even seemingly modest early works presaged the coloristic and emotional intensity of his later periods.

Critical Reception and Scholarly Interpretation

Early art historians often overlooked Van Gogh’s Dutch period in favor of the more dramatic Arles and Saint-Rémy paintings. Yet since the 1970s, scholars have reappraised these early landscapes for their foundational role in his artistic evolution. Critics have noted “Flower Beds in Holland” for its compositional daring—unusual for the time in its close cropping and low viewpoint—and its tentative color explorations anticipating his break from Dutch tonalism. Recent scholarship situates the work within the broader context of 19th-century plein-air painting, arguing that Van Gogh’s experiments with light and hue in the bulb fields reflect contemporary debates on Impressionist technique, even as he maintained his own distinct vision.

Legacy and Influence on Landscape Painting

Although overshadowed by his later masterpieces, “Flower Beds in Holland” has inspired modern artists interested in the interplay of agriculture and color. Contemporary painters of rural scenes often reference Van Gogh’s early Dutch works to explore geometric field patterns and seasonal atmospheres. The painting’s combination of structure and spontaneity resonates with artists who seek to balance human design with natural growth in their own landscapes. Moreover, the canvas serves as a teaching model in art academies for understanding how to build depth, manage subdued light, and move toward a more daring palette. Its rediscovery has enriched appreciation for Van Gogh’s full career, showing that his genius was present well before his Provençal explosion of color.

Conclusion: A Foundational Vision of Pattern and Color

In “Flower Beds in Holland,” Vincent van Gogh transforms a commonplace agricultural scene into a compelling exploration of color, composition, and human endeavor. Painted at a moment of personal and artistic transition, the work marries the disciplined geometry of bulb cultivation with the emotive potential of a bolder palette. Through deft brushwork and subtle tonal harmonies, Van Gogh captures both the industrious spirit of the Dutch bulb fields and a quiet emotional undercurrent—anticipating the more dramatic landscapes that would follow in his later years. As an early testament to his evolving style, this painting reminds us that Van Gogh’s search for meaning through art was as vivid amid the flat northern fields as it would become beneath the Provençal sun.