Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

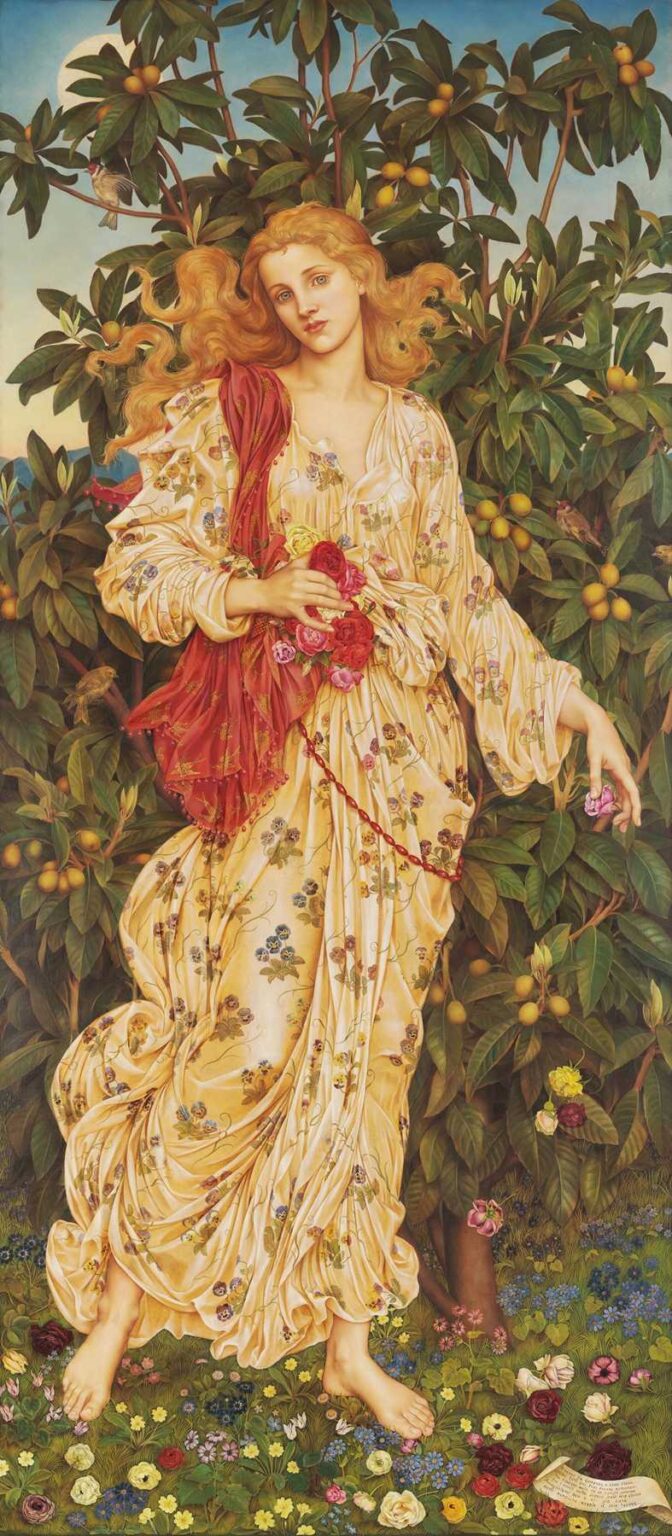

Evelyn De Morgan’s Flora (1894) is a luminous testament to the late‐Victorian revival of classical myth and the Pre‑Raphaelite celebration of natural beauty. Measuring nearly six feet tall, the painting presents us with the Roman goddess of flowers and spring, rendered with breathtaking precision in oil on canvas. Against a backdrop of rippling blue sky and lush foliage—including an orange‐bearing tree and a moonlit canopy—Flora walks barefoot across a carpet of freshly opened blossoms, scattering petals at her feet. She wears a diaphanous gown printed with pansies and bound by a scarlet scarf, her flowing golden hair echoing the sunlight in which she stands. At her right hand hangs a scroll inscribed with lines by the poet Shelley, further linking De Morgan’s work to literary and classical traditions. In Flora, De Morgan synthesizes symbolism, botanical accuracy, and a luminous painterly technique to create a portrait of eternal spring—an allegory of regeneration, beauty, and the enduring power of nature.

Historical and Cultural Context

Painted in 1894, Flora emerges near the height of Evelyn De Morgan’s career, at a moment when she had fully absorbed both the aesthetic precepts of the Pre‑Raphaelites and the intellectual currents of Symbolism and spiritualism. The latter half of the nineteenth century in Britain saw increasing fascination with classical mythology, driven by archaeological discoveries and scholarship that brought ancient deities back into popular imagination. Simultaneously, the Age of Empire witnessed a renewed interest in moral and philosophical reform, with art intended not merely to delight the senses but to elevate the spirit. De Morgan—an ardent Theosophist and feminist—used mythological figures like Flora to explore themes of feminine power, cyclical renewal, and the intrinsic unity of beauty and virtue. Flora, therefore, stands at the confluence of aesthetic exuberance, mythic revival, and social idealism that defined De Morgan’s generation.

Subject and Iconography

At the heart of Flora is the Roman goddess of flowers and spring, whose very name derives from the Latin for “flower.” De Morgan portrays Flora as an earthly embodiment of blooming life: her feet tread lightly on a meadow bursting with roses, forget‑me‑nots, primroses, and pansies, each meticulously painted with botanical accuracy. The wreath of roses she holds close to her chest signifies the onset of flowering season, while additional blossoms spill from her hand, symbolizing her generous bestowal of nature’s bounty.

Behind her, a tree heavy with golden fruit suggests the abundance of the earth and the interdependence of flora and fauna. A small bird perched among the leaves further enlivens the scene, while the full moon rising behind the branches introduces a nocturnal element, linking the cycles of growth to lunar rhythms. At Flora’s feet lies a scroll bearing Shelley’s verse, anchoring the painting in a broader literary and philosophical tradition. By blending classical mythology, symbolism, and poetry, De Morgan elevates Flora from a simple garden scene to an allegory of cosmic renewal.

Composition and Spatial Structure

De Morgan arranges Flora within a narrow vertical format—reminiscent of ecclesiastical panels or Renaissance predellas—that enhances the painting’s sense of ascension and grace. The figure of Flora dominates the central axis, her body creating a subtle S‑curve: her left foot steps forward, her torso twists gently, and her head tilts in a soft arc, lending the figure an effortless fluidity. This dynamic pose, combined with the billowing folds of her gown, conveys motion even as the goddess stands nearly full‑face to the viewer.

The dense foliage behind Flora forms a green halo that frames her luminous figure, while the sky above—pale and gradually deepening toward the canvas edges—provides a serene counterpoint. The interplay of verticals (tree trunks, the scroll) and horizontals (the horizon line, the planes of the meadow) establishes a stable yet lively spatial architecture, guiding the viewer’s gaze from the earthly flowers at the bottom, up Flora’s flowing form, and into the distant ether of the moonlit sky.

Color Palette and Light

Color in Flora is at once naturalistic and heightened, embodying the artist’s intention to evoke an otherworldly springtime glow. The gown’s pale yellow serves as a tissue for delicate blossom motifs, harmonizing with the warmer petals at Flora’s feet. The scarlet scarf draped over her shoulder introduces a dramatic pulsation of color, both accentuating her generous curves and symbolizing the vitality of life.

Flora’s golden hair shimmers with subtle highlights, each strand meticulously rendered to capture the effect of sunlight filtering through leaves. The surrounding greenery encompasses a spectrum of emerald and olive tones, enlivened by dabs of lemon in the fruit and pale silver in the moon’s bloom. The sky’s blue gradation—from the palest dawn to a soft cerulean—underscores the painting’s transitional time of day, straddling night and morning. De Morgan’s nuanced layering of glazes and tempera techniques yields a surface that both glows internally and captures the crispness of a spring sunrise.

Technique and Painterly Execution

De Morgan’s technique in Flora combines the Pre‑Raphaelite commitment to detail with a fluid brushwork that prefigures later Symbolist paint handling. Underlying pencil or charcoal sketches define the composition’s precise outlines. Over these, De Morgan applied thin oil glazes to build luminous skin tones and to achieve botanical verisimilitude in each petal and leaf. Subtle impasto accents—visible in the highlights on petals or the birds’ feathers—add textural contrast without disrupting the overall polished surface.

Her mastery of layering allows minute reflections of underpainting to emerge through upper passages, creating optical vibrancy. The drapery’s shadows are rendered with cool blues and violets rather than simple brown or black mix, enriching depth. Meanwhile, the fine gold‐leaf touches in the scroll’s script and the faint filigree on the red scarf’s border speak to a decorative refinement that aligns with De Morgan’s interest in applied arts and her connection to William Morris’s circle.

Flora’s Expression and Presence

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Flora is the goddess’s serene yet compelling gaze. Her large, almond‑shaped eyes look directly—or softly—toward the viewer, conveying both directness and otherworldliness. Her slightly parted lips and relaxed pose suggest a living ardor for beauty, tempered by divine calm. This blend of human warmth and transcendent poise typifies De Morgan’s portrayal of women: radiant beings endowed with spiritual agency rather than passive muses.

Flora’s gesture—her hand gently cradling blossoms—conveys nurturing generosity, while the other hand, extended, suggests an invitation to share in the beauty of spring. Through subtle modulation of facial features and body language, De Morgan animates Flora with a presence that feels both idealized and intimately relatable, inviting empathic connection rather than mere idolization.

Literary and Philosophical Underpinnings

The inclusion of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poetry anchors Flora in the Romantic literary tradition, wherein nature serves as a conduit to the divine and as a mirror of the human soul. Shelley’s lines—carefully selected by De Morgan—underscore themes of rebirth, hope, and the ephemeral yet eternal quality of beauty. This interweaving of text and image reflects the Victorian penchant for ekphrasis and the belief that poetry and painting could collaborate to convey deeper truths.

Evelyn De Morgan’s own spiritual convictions—shaped by Theosophy and feminist ideals—infuse Flora with philosophical resonance. The goddess, though drawn from classical pantheon, represents a universal principle: the cyclical renewal of life, the intrinsic link between human and natural realms, and the imperative of stewardship that De Morgan saw as both moral and ecological.

Ecological and Feminist Reading

Modern viewers can locate an ecological subtext in Flora: the painting’s obsessive botanical detail and its reverence for plant life anticipate later concerns about environmental preservation. By positioning Flora as custodian of blossoms and fruit, De Morgan subtly champions a harmonious relationship between humanity and nature—a theme that resonates with contemporary ecological discourse.

From a feminist perspective, Flora asserts a model of female power grounded in creation rather than dominion. The goddess commands the scene not through martial or domestic imagery, but through her role as nurturer and bearer of life‐affirming beauty. De Morgan’s consistent elevation of such female archetypes across her oeuvre marks her as a proto‑feminist artist, using mythological subjects to reframe women’s roles in both art and society.

Reception and Place in De Morgan’s Oeuvre

Upon its exhibition in 1894 at the New Gallery in London, Flora garnered praise for its exquisite finish, harmonious composition, and the deft integration of myth and nature. Critics lauded De Morgan’s technical skill and the painting’s uplifting mood. Over the years, Flora has become emblematic of De Morgan’s mature style, illustrating her capacity to blend Pre‑Raphaelite precision with Symbolist depth.

As art historians have reevaluated women artists of the Victorian era, Flora has featured prominently in retrospectives highlighting De Morgan’s contributions. The painting’s enduring appeal lies in its timeless beauty and the rich layers of meaning available to successive generations of viewers.

Conclusion

Evelyn De Morgan’s Flora remains a radiant exemplar of late‑Victorian art at its intersection of myth, nature, and moral purpose. Through her masterful use of color, impeccable botanical detail, and evocative allegory, De Morgan transforms the classical figure of the goddess into a living manifestation of spring’s regenerative power. Flora invites us to reflect on our own relationship with the natural world, the cyclical rhythms of life, and the feminine force of nurturing creativity. Over a century after its creation, the painting continues to bloom in the collective imagination, affirming art’s capacity to renew our sense of wonder and to remind us of the beauty ever unfolding beneath our feet.