Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

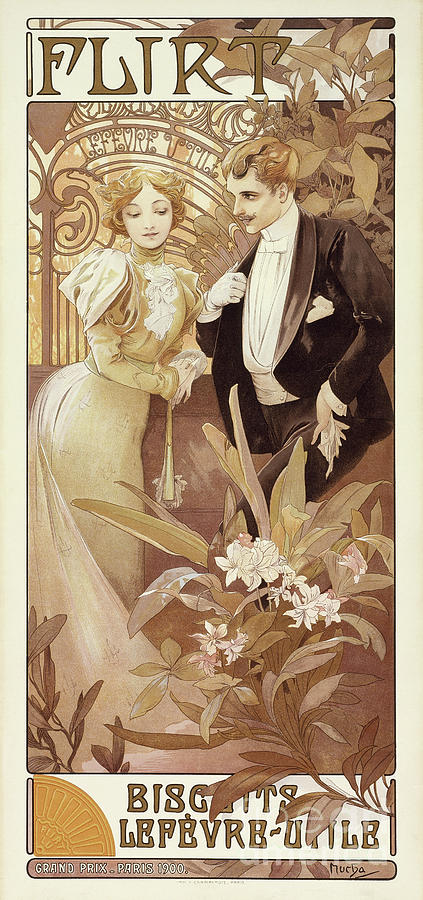

Alphonse Mucha’s “Flirt Lefèvre Utile” (1899) captures a moment of Belle Époque courtship and turns it into a refined theater of taste. Commissioned by the celebrated Nantes biscuit maker Lefèvre-Utile, the poster stages a gentle exchange between a young woman and a tuxedoed suitor in a garden of stylized blooms. Everything about the scene is curated to make desire feel elegant: the sweeping arabesques, the satin coolness of gloves, the lacquered shine of the man’s lapels, the whispering leaves that frame their faces. Rather than shouting about biscuits, Mucha invites the viewer into a story where the brand appears not as a product shot but as a gracious host of romance.

Lefèvre-Utile and the Art of Seductive Advertising

By the 1890s Lefèvre-Utile had become a pioneer in modern advertising, commissioning artists to build a world of associations around its initials “LU.” The firm understood that pleasure sells pleasure, and that a box of delicate biscuits could be made to signify social ease, good taste, and flirtatious wit. Mucha was an ideal collaborator. Fresh from his triumphs in Parisian poster art, he knew how to fold allegory, typography, and ornament into persuasive narratives. “Flirt Lefèvre Utile” aligns the brand with the manners of a well-appointed salon: a place where sweets accompany conversation and where ritual is performed in the language of gestures.

A Carefully Composed Encounter

The composition is a tall rectangle with rounded corners, a format Mucha favored for domestic display. Within it he stages a duet. The woman stands slightly left of center, turning toward the man who leans in from the right. Their bodies form a shallow V that opens toward the viewer, inviting us into their space. The diagonal thrust of large plant stems in the foreground propels the scene upward, while the balcony grille and arbor behind them curve into a protective arch. The arrangement feels at once intimate and theatrical, like a stage set that allows privacy inside public life.

The Theater of Gesture

Mucha tells the entire story through hands. The woman’s gloved fingers lightly lift a biscuit to her mouth, a coded gesture of refinement and appetite. The man’s right hand rests near his lapel while his left extends, either offering a small packet or simply directing conversation, an elegant move balanced between proposal and discretion. Their faces amplify the choreography: her gaze is lowered and inward, preserving modesty; his is angled and intent, communicating interest without pressure. This is flirtation as a game of timing and restraint, captured at the exact moment before a smile breaks.

Costume and Social Codes

Clothing defines the social temperature of the scene. The woman wears a pale gown cut close at the bodice, with poufed sleeves and a high lace collar that speaks of propriety even as the silhouette hints at the body beneath. Gloves enforce decorum, turning eating into a ritual rather than a necessity. The man’s evening suit gleams in deep blacks and olives, with a white shirtfront that mirrors the white blossoms below. A boutonnière repeats the floral motif and marks him as a guest in a world where details matter. These costumes signal a sociable class that consumes with style.

Palette and Atmosphere

The color scheme is built from café creams, tea browns, olive greens, and a breath of lavender, unified by the warm light of the lithographic paper. The palette is edible without being literal, evoking caramelized sugars, biscuit crumb, and candied violets while remaining thoroughly urbane. Mucha avoids harsh contrast; edges are defined by a dark keyline, but the tones blend like conversation. This chromatic harmony makes the poster live comfortably on a wall, casting a gentle glow even in dim cafés and shop windows.

Ornament as Emotional Architecture

The garden is not a botanical study but a network of arabesques that structures feeling. Leaves rise in elongated, flame-like tongues; stems bend in soft parabolas; blossom clusters hover like perfumed clouds. Behind the couple, an Art Nouveau grille loops in a repeated motif that rhymes with the letterforms of FLIRT above. Ornament here is not filler. It is the emotional architecture of the scene, enclosing the pair in a mood of privacy, abundance, and cultivated nature.

The Language of Flowers

Mucha’s flowers do double duty as design and symbol. White blossoms near the man echo his shirtfront and suggest purity of intention, while the more complex sprays near the woman combine warmth and delicacy. Petals curl like whispers, and their placement creates a visual bridge between faces and hands. The floral world is a chorus singing under the dialogue, reminding the viewer that taste in the mouth and scent in the air are partners in pleasure.

Typography that Belongs to the Picture

The word FLIRT crowns the image with a firm, stylized confidence. Its black strokes are flared and tapered to match the whiplash rhythms of the surrounding ornament. At the base, “BISCUITS LEFÈVRE-UTILE” occupies a white cartouche framed by a wedge of biscuit rendered like a gleaming seal. The lettering is integral to the composition; it reads at distance yet feels woven into the scene. Even the small line “GRAND PRIX, PARIS 1900” functions as a satin ribbon tying the brand to international prestige without breaking the picture’s tone.

The Biscuit as Emblem

Instead of a literal product display, Mucha places a stylized biscuit segment in the lower left. The radial pattern on its surface catches the eye like a medallion. This choice lifts the brand above mere retail; the biscuit becomes a token of membership in the world the poster describes. Set beside the lush plants, the emblem suggests cultivation and craft, aligning the confection with natural abundance shaped by human skill.

Lithographic Craft and Paper Light

Color lithography gives the poster its signature softness. Transparent inks allow the cream paper to act as internal light, illuminating the woman’s face, the man’s shirtfront, and the white flowers without chalky paint. The keyline defines forms with calligraphic certainty while allowing midtones to breathe. In the leaves and hair, one can see the grain of crayon on stone, preserving a hand-drawn liveliness that keeps the elegance from becoming sterile. The print feels warm and tactile, like a conversation held close to the glow of a lamp.

The Gaze and the Politics of Charm

Mucha’s women are often described as muses, yet here the woman is also the chooser. Her downward eyes and measured gesture propose agency contained within etiquette. The man’s eagerness is tempered by distance; he leans in but does not crowd. This balance grants dignity to both figures and positions Lefèvre-Utile as a brand that understands modern social intelligence. Pleasure is mutual, orchestrated through consent and style.

Consumption as Conversation

The poster presents eating not as appetite sated in solitude but as a shared act that oils the gears of sociability. The biscuit is light enough to be held while speaking, crisp enough to punctuate a sentence, sweet enough to warm the air without claiming it. This reframing of a simple product as a conversation partner is central to the brand’s genius and to Mucha’s strategy. He sells a scenario rather than a snack.

A Belle Époque Snapshot

“Flirt Lefèvre Utile” is also a time capsule of 1890s Paris. The setting evokes winter gardens and conservatories where the bourgeoisie promenaded among exotic plants. The couple’s fashion marks that precise hinge between the bustle and the S-curve of Art Nouveau. The poster’s language—both in words and images—assumes a city attuned to nuance, where afternoons were structured by cafés, theaters, and strolls. To own the poster, or to buy the biscuits, was to participate in that choreography.

The Viewer’s Path Through the Scene

Mucha guides the viewer with unhurried certainty. Eyes enter at the title, slide down through the arching grille to the woman’s face, cross to the man’s intent profile, then drop to the white blossoms and the biscuit emblem before returning up the stems to the pair. The loop is easy and repeatable, ideal for a street poster that must catch passing glances and reward longer looks. Meanwhile, the long vertical format stretches the narrative like a breath held before a reply.

Comparisons within the LU Campaigns

Lefèvre-Utile posters often featured women with baskets or ribbons forming literal “LU” monograms. Here Mucha chooses a subtler approach. The initials appear in the brand name while the spirit of LU—lightness, elegance, sociability—pervades the picture. Compared with the artist’s more theatrical celebrity posters, this sheet is intimate, almost whispering. The restraint suits a confection whose power lies in refinement rather than spectacle.

Ornament that Organizes

One of the poster’s triumphs is its ability to be rich without cluttered. Each motif stabilizes the whole. The balcony grille locks the upper area together and frames the title. The parallel stems in the foreground counter the diagonal lean of the man’s body and weight the composition. The biscuit medallion balances the mass of blossoms above it. The white cartouche rests like a baseboard, carrying the brand and completing the architectural feel. Everything decorative is load-bearing.

The Afterlife of a Gentle Image

More than a century later, “Flirt Lefèvre Utile” continues to circulate because its promise remains irresistible. It offers a model of civility where appetite and charm cooperate, where design flatters the eye, and where a small treat can change the tone of an afternoon. Contemporary branding still borrows from its lessons: sell a mood, integrate type with image, limit the palette, and let narrative do the heavy lifting. The poster’s gentleness is its strength; it lingers like a pleasant memory.

Conclusion

“Flirt Lefèvre Utile” is a miniature drama of manners, staged in the language of Art Nouveau line and lithographic light. A couple meets among flowers; a glance becomes an invitation; a biscuit becomes a token of taste. Mucha unites costume, gesture, ornament, and typography so seamlessly that the commercial purpose feels like the natural conclusion of the story. The poster does not claim that biscuits will change your life; it suggests they will make your best moments more fluent. In that suggestion lies its lasting magic.