Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context: Paris in 1887 and Van Gogh’s Artistic Evolution

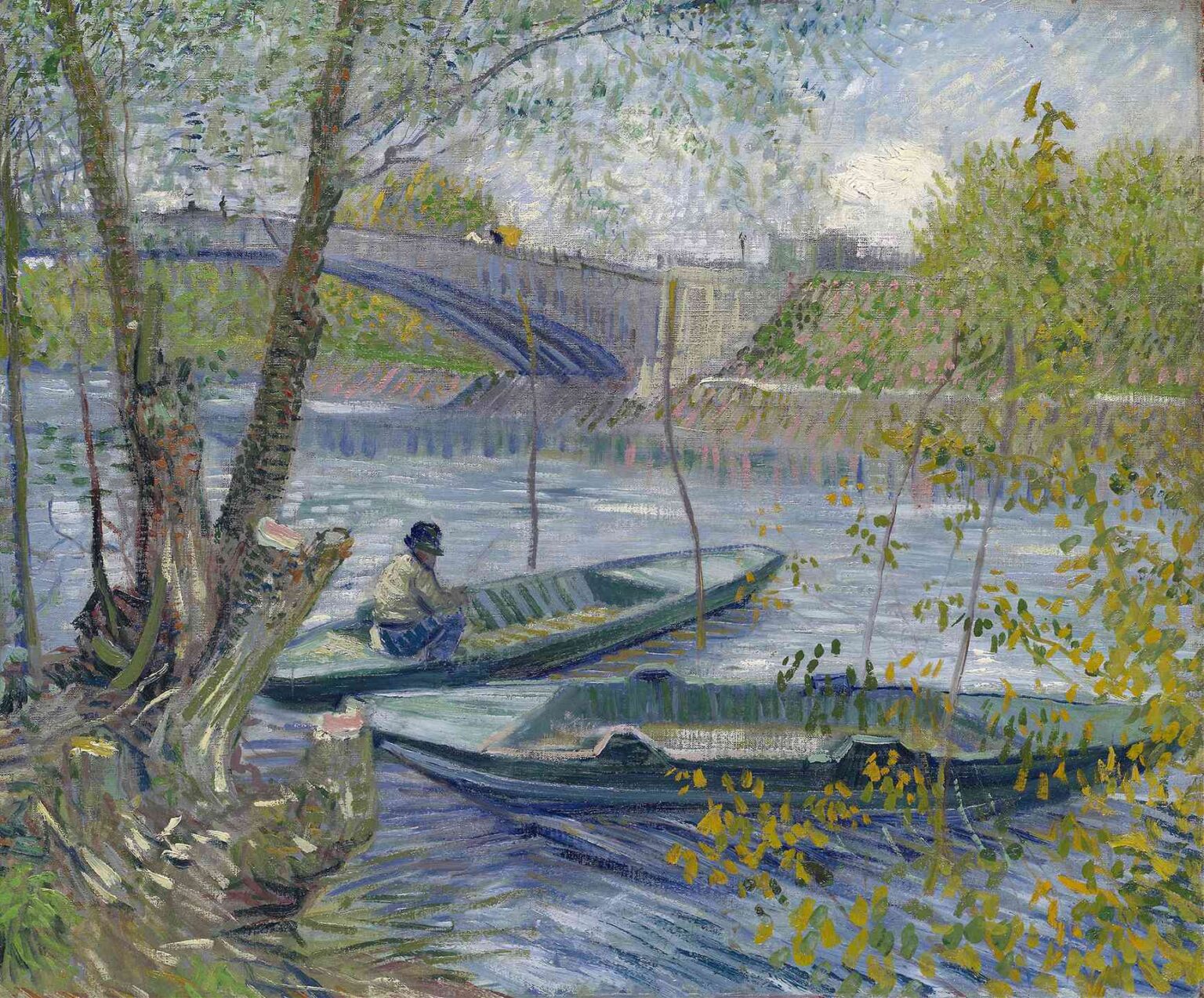

In March 1887, Vincent van Gogh relocated from the pastoral calm of Nuenen to the vibrant metropolis of Paris. Lodging with his brother Theo in the Montmartre district, he found himself amid the throes of Impressionism, Symbolism, and the nascent Neo-Impressionist experiments with Divisionism. Here Van Gogh absorbed new theories of color and light, encountered the pointillist techniques of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, and collected Japanese ukiyo-e prints that would inform his compositional flatness and decorative patterning. It was in this crucible of innovation that he painted “Fishing in Spring, the Pont de Clichy” (1887), a work that synthesizes his Dutch realism with Parisian chromatic daring. This canvas marks a turning point: nature is no longer rendered solely as backdrop but becomes an active participant in the emotional drama of the scene.

The Pont de Clichy: Industrial Landmark as Visual Anchor

Spanning the Seine northwest of central Paris, the Pont de Clichy was a symbol of modern industry and urban expansion in the late nineteenth century. Van Gogh found in its iron structure and stone masonry a striking counterpoint to the organic ripples of water and the budding willow branches that he often sketched along the riverbanks. In “Fishing in Spring, the Pont de Clichy,” the bridge occupies the middle ground, its arcing silhouette bisecting sky and river. By placing the human activity of fishing in direct dialogue with this engineered landmark, Van Gogh underscores the tension between nature and human intervention—a theme he would revisit in subsequent Auvers‐sur‐Oise waterways and wheatfield paintings.

Subject and Narrative: Fishermen at Dawn

The painting depicts two fishermen perched in a slender punt, lines cast into the Seine as dawn’s first light tinges the sky. Their figures are small, almost anonymous, yet their posture—slightly stooped, intent on the water—conveys a universal ritual of labor and reflection. On the riverbank, a cluster of willows and alder trunks frame the left edge, their new spring leaves rendered in soft pistachio and sage. Across the bank, faint outlines of factory chimneys and distant buildings hint at Paris beyond, anchoring the scene in a specific locale. Van Gogh elevates this quotidian moment into a meditation on human engagement with the environment, where the act of fishing becomes a symbol of hope, patience, and the promise of renewal.

Composition and Spatial Organization: Layers of Engagement

Van Gogh structures the canvas into three horizontal planes: the leafy foreground with its dappled sunlight and knotted trunks; the mid-section where the fishermen and boats drift; and the distant horizon of bridge and industrial skyline. This banding creates depth, yet the overlapping of brushstrokes defies strict linear perspective. The willow branches arch downward, inviting the viewer’s eye into the scene, while the river’s ripples direct attention diagonally toward the opposite bank. The fishing line, subtle yet taut, extends the vertical axis, connecting sky to water and human presence to natural expanse. The result is an immersive environment that balances tranquility with dynamic motion.

Palette and Light: Spring’s Chromatic Symphony

Unlike his earlier Dutch canvases marked by somber earth tones, Van Gogh’s spring palette for “Fishing in Spring, the Pont de Clichy” is unexpectedly bright. He layers delicate greens—apple, celadon, olive—in the foliage, punctuated by hints of buttery yellow where sunlight catches new leaves. The water shimmers with reflections of lavender, cerulean blue, and pale rose, each hue applied in short, rhythmic strokes. The sky, streaked with milky white clouds tinged in lilac, bathes the entire scene in a gentle, diffused light. Through these color relationships, Van Gogh communicates the season’s sense of awakening: the world is alight with possibility, and every ripple and leaf vibration becomes a testament to life’s renewal.

Brushwork and Technique: From Divisionism to Expressive Mark

In Paris, Van Gogh experimented with Divisionist principles—applying small dots or dashes of pure pigment that optically blend at a distance—but he never adhered to the technique’s strictures. In “Fishing in Spring,” his brushwork is a hybrid: the foreground grasses and riverbank are built from sinuous, almost calligraphic strokes, while the water’s surface features broken horizontal dashes that simulate the refraction of light. The fishermen and their boat are rendered with broader, more confident arcs, suggesting solidity amid the fluid atmosphere. Van Gogh’s impasto is moderate here, allowing underlying underpainting to peek through and enrich the overall vibrancy. His handling of paint thus becomes a visual echo of the scene’s rippling energy.

Seasonal Atmosphere: Capturing Spring’s Ephemeral Mood

Spring in Paris was famously brief yet intense, as winter’s gray receded and the city’s parks and riverbanks burst into bloom. Van Gogh’s painting captures this fleeting quality through his choice of subject and technique. The young leaves on the willows are depicted with swift upward flicks, while the distant bank’s pink and white blossoms appear as tiny mosaic-like dabs. The fishermen’s dark figures and the sturdy boat, painted in cool blues and grays, anchor the transient palette to the permanence of human endeavor. Air seems to circulate within the canvas, as though the viewer could feel the faint breeze stirring the buds and the fishermen’s hair. Van Gogh transforms atmospheric observation into painterly poetry.

Symbolism and Thematic Resonance: Nature, Industry, and Human Persistence

Beneath the surface depiction of a serene morning, “Fishing in Spring, the Pont de Clichy” explores deeper themes. The bridge stands for the march of progress, its rigid lines contrasting with the organic vitality of the foliage. The act of fishing suggests patience, the hope for sustenance, and the human desire to connect with nature’s rhythms. In Van Gogh’s letters he often equated fishing with spiritual contemplation—casting one’s line into the unknown in search of nourishment for both body and soul. The interplay of industry and tradition, of technology and pastoral ritual, becomes a microcosm of modern life’s contradictions, rendered with empathy rather than judgment.

Relationship to Van Gogh’s Other Works: Dialogues Across Time

While Van Gogh’s later Auvers‐sur‐Oise canvases often focus on wheatfields, cypress trees, and village churches, “Fishing in Spring” belongs to his earlier Paris period, when he sought new motifs along the Seine. It prefigures paintings such as “Fishing Boats on the Beach at Saintes-Maries” and “Ponte di Trinquetaille” in Arles, where water and craft become recurring subjects. Yet here the urban backdrop and the presence of manufactured architecture differentiate it: it is simultaneously a landscape, a genre scene, and a commentary on progress. The sense of immediacy and sunlight uniting natural and man-made elements anticipates Van Gogh’s southern color explosion, while retaining a Northern attention to detail.

Technical Insights and Conservation Notes

Scientific analysis of “Fishing in Spring” reveals Van Gogh’s limited Paris palette of lead white, chrome yellow, viridian, cobalt blue, and small amounts of red lake. Infrared reflectography shows a delicate underdrawing—likely sketched in pale charcoal—guiding the composition. The paint layer is relatively thin, allowing for subtle layering of glazes that intensify after conservation cleaning. X-ray fluorescence indicates that the willow trunks contain high concentrations of earth pigments mixed with Prussian blue, giving them a mossy patina. Conservation records note minimal craquelure, attesting to the painting’s stable condition despite decades of display in fluctuating climates.

Provenance and Exhibition History

After Van Gogh left Paris for Arles in 1888, “Fishing in Spring, the Pont de Clichy” remained with his brother Theo, who exhibited it at the Galerie Boussod & Valadon in 1892. Following Theo’s death, it passed to Jo van Gogh-Bonger, and then to private collectors in Brussels and Amsterdam. By the early twentieth century, it had entered a prominent European museum collection, where it featured in landmark exhibitions of Post-Impressionist works. Each display context—from “Van Gogh and the City” retrospectives to thematic shows on industrial landscapes—has highlighted its unique fusion of urban subject matter and pastoral sensitivity.

Critical Reception and Scholarly Interpretations

Early critics praised the painting’s fresh light and handling of color but were divided over the juxtaposition of industrial structure and rural activity. Mid-century art historians lauded its role in bridging Impressionism and Expressionism, emphasizing its emotive brushwork as a precursor to Van Gogh’s later style. Marxist critiques have read the canvas as a commentary on labor and the exploitation implicit in industrial expansion, while eco-critics focus on its depiction of nature’s resilience amid human intrusion. More recent interdisciplinary studies explore its neuroaesthetic impact, noting how the broken brushstrokes and color juxtapositions engage viewers’ visual cortex in patterns of immersion.

Legacy and Influence on Modern Landscape Painting

“Fishing in Spring, the Pont de Clichy” has inspired artists exploring the interplay of urbanity and nature. Early twentieth-century painters like Édouard Vuillard cited Van Gogh’s Seine scenes as models for integrating human figures into complex environments. Contemporary landscape artists, working in mixed media and abstraction, reference the painting’s layered brushwork and chromatic dynamics. In photography and film, sequence shots of riverside leisure owe a conceptual debt to Van Gogh’s visual structure: framing human activity against a broader environmental and industrial backdrop. The canvas remains a touchstone for any creative exploration of modern life’s nexus between progress and pastoral tradition.

Conclusion: A Harmonious Convergence of Worlds

Vincent van Gogh’s “Fishing in Spring, the Pont de Clichy” stands as a testament to his ability to fuse disparate elements—industry and nature, labor and leisure, structure and spontaneity—into a single, compelling vision. Through his vibrant spring palette, dynamic brushwork, and empathetic portrayal of two quiet figures on the Seine, he transfigures a simple morning ritual into a universal meditation on human persistence and environmental resonance. By situating his fishermen before the modern arch of the Pont de Clichy, Van Gogh invites viewers to reflect on the delicate balance between human ambition and the timeless rhythms of the natural world.