Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

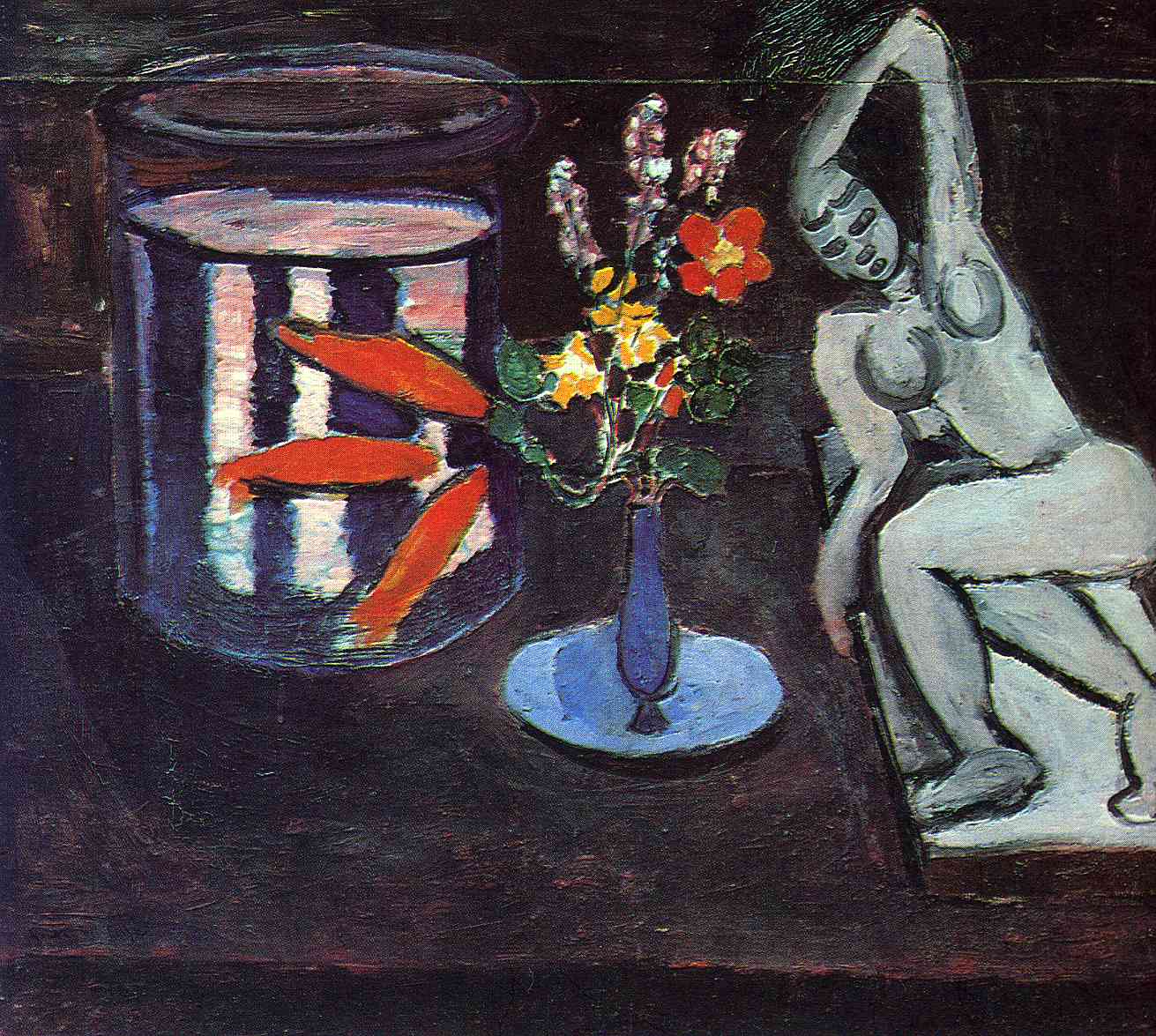

Henri Matisse’s “Fish tank in the room” (1912) stages a meeting between three kinds of studio presences: living creatures gliding in water, cut flowers arranged in a slim vase, and a sculpted figure frozen in a stretched pose. The cylindrical bowl with its bright orange fish anchors the left half of the canvas; a small bouquet punctuates the center; to the right, a pale, stylized nude leans and arcs an arm above her head. All of this is set against a dark interior that feels at once intimate and theatrical. The painting is a concentrated statement of Matisse’s art in 1912, when he turned everyday objects into charged actors by orchestrating color contrasts, simplified shapes, and a rhythm of lines that guide the eye like music.

Historical Moment

The year 1912 is pivotal for Matisse. He is fresh from his first Moroccan sojourn, where intense light and the rituals of looking reshaped his sense of pictorial economy. Around this time he repeatedly paints goldfish, fascinated by their calm, looping movements and the way glass, water, and reflection produce optical puzzles that painting can translate into clear form. At the same moment, Cubism is analyzing forms into facets, but Matisse follows a different modern path, building coherent images with large color fields and arabesque contours. “Fish tank in the room” belongs to this exploration. It compresses the studio—the private laboratory of making—into a tableau where modern color and timeless motifs coexist.

The Goldfish Motif

Goldfish are more than decorative subjects in Matisse’s work. He admired the languid, meditative way people in North Africa contemplated fish bowls, and he brought this idea of serene looking back into the studio. In this painting the fish are simplified to tapered flames of orange that drift horizontally in a cylindrical container. Their movement is implied rather than described: no splash, no ripple, only the gentle curve of their bodies. The motif lets Matisse investigate how living motion can be conveyed by color alone and how the distortion of glass can become a painterly device. The fish embody a calm vitality that infuses the whole composition.

Composition and Geometry

The canvas is structured like a still-life stage. The big cylinder at left, the thin vase at center, and the sculpted figure at right form a measured progression from heavy volume to slender vertical to articulated body. These three anchors create a slow rhythm: circle, spindle, limb. The circular mouth of the bowl sets up the dominant geometry; it repeats as a faint ellipse in the saucer under the vase and as rounded knees and head within the sculpture. The arrangement is frontal—objects are pushed toward the picture plane—yet the overlaps and the diagonals of the sculpture’s limbs create a dynamic Z-shaped movement from left foreground to right background.

Color Architecture

Matisse’s palette is deliberately restricted and high-contrast. Dark violets and midnight blues form the ground of the room, while bright accents—orange fish, red and yellow flowers, the pale blue vase, and the cool stone of the sculpture—strike against it. The complementary opposition of blue and orange powers the painting: the fish flare like embers inside a deep cobalt vessel. The blue of the vase, only slightly lighter than the surrounding darks, holds the center quietly, a hinge between the living fish and the lifelike sculpture. Color here is structure; it assigns roles to the actors and calibrates the emotional temperature of the space.

Light, Reflection, and Glass

The glass bowl multiplies realities. Vertical bands—perhaps reflections of a window or studio partitions—curve around the cylinder, bending white into lavender and blue as they follow the surface. These stripes also act like bars, a witty counterpoint to the fish’s freedom of motion. At the waterline, pale highlights skim the rim, giving the vessel its material presence. Matisse does not chase naturalistic sparkle; instead, he isolates a few decisive reflections that declare both the roundness of the bowl and the flatness of the painted surface. The eye toggles between illusion and design, which is precisely the kind of looking the artist cultivates.

The Bouquet as Pictorial Pivot

Placed between fish and sculpture, the bouquet is small but crucial. Its yellow and red blossoms echo the colors of the fish, creating chromatic bridges across the composition. The green leaves supply the only strong green note, mediating between blue ground and orange accents. The narrow neck of the vase lifts the flowers into the air like a short solo between two larger orchestral passages. Without the bouquet, the painting would divide into a left-right duel; with it, the scene reads as a coherent triad.

The Sculpture’s Role

The stone figure on the right is not a passive prop. It leans, bends an arm, and twists the torso in a pose that radiates slow energy. Its pale, cool tones make it read as carved matter, but the simplified planes and dark outlines tie it to the language of painting rather than academic statuary. Conceptually, the sculpture offers a counterpoint to the fish: one is life suspended in water; the other is life arrested in stone. Together they bracket the bouquet, which is life cut and arranged. Matisse thereby stages a meditation on the states of living—moving, held, and transformed into art—within one studio scene.

Drawing and Line

Matisse’s line is firm but elastic. The rim of the bowl reads with a single sweep; the fish are defined with swift, tapered contours; the sculpture’s anatomy is simplified into confident arcs and angles. He relies on the interaction of colored planes to describe form, letting lines emerge where two tones meet. When an explicit outline appears, it is purposeful, as in the dark edges of the figure that clarify the pose against the surrounding gloom. Across the surface, the eye follows a continuous arabesque—from the curve of the bowl, through the stem of the vase, into the lifted arm of the sculpture—binding disparate elements into one gesture.

Space Without Perspective

Traditional depth cues recede here in favor of a shallow, coherent stage. The tabletop tilts gently, but the strong horizontals of the background hold the space near the surface. Depth is achieved primarily by overlap: the vase overlaps the bowl, and the sculpture slips behind the plane of the table. Color also does the spatial work: warm accents advance; cool, dark fields sit back. The result is a space that is believable but intentionally compressed, the better to make color relationships legible and intense.

Rhythm and Repetition

Repetition subtly organizes the composition. The fish repeat in size and orientation, forming a band of orange notes. The vertical reflections in the bowl rhyme with the vase’s slim neck. The rounded forms of fish, flowers, and the sculpture’s articulated joints establish a thematic circularity that answers the bowl’s big rim. Even the dark background contains faint horizontal seams that steady the beat. Though still, the painting feels musical because each form answers another across the surface.

Material Surface and Brushwork

The paint handling alternates between smooth, opaque fields and visibly worked passages. In the bowl, strokes curve to follow the cylinder; in the dark ground, pigment is dragged and scumbled, allowing a low shimmer of underlying color to break through. The fish themselves are laid in with concentrated, full-bodied strokes that leave small ridges of paint—physical proof of their presence. The sculpture, by contrast, is modeled with broader, softer sweeps, reinforcing its stone-like calm. Throughout, Matisse leaves just enough of the making visible to keep the image alive without sacrificing the clarity of the forms.

Psychological Atmosphere

Despite the bright fish and flowers, the room feels quiet, even nocturnal. The prevailing darks create a hush in which the oranges and yellows glow with special intensity. The composition suggests attention rather than activity: this is a space for looking. The fish, the bouquet, and the sculpture appear absorbed in their own states. Viewers, drawn close by the shallow space, join this circle of concentration. The painting becomes a picture about thoughtful seeing—about giving ordinary things the dignity of prolonged regard.

Studio as Theatre

Matisse often treated his studio as a stage where different arts—painting, sculpture, decoration, and living nature—could appear together. Here he literally gives the sculpture a seat on the platform of the table, as if introducing a performer. The fish bowl is a small aquarium theater, complete with reflective backdrop; the bouquet, like a costumed extra, supplies color accents. The dark setting is a velvet curtain that makes the actors pop. This theatrical framing turns the private activity of looking into a ceremonial experience.

Dialogue with Other Works of 1912

“Fish tank in the room” converses with Matisse’s numerous goldfish paintings from the same year. Some present the bowl against light-filled interiors; others place it near windows or patterned fabrics. Compared to those, this version is more nocturne-like, emphasizing contrast and the intimacy of near-black grounds. The presence of the sculpture links it to his ongoing reflection on the relationship between painting and sculpture, a reflection also seen in earlier studio canvases where painted and sculpted figures share space. The persistent return to the goldfish motif demonstrates how Matisse uses repetition to refine color problems until they become solutions.

Conversation with Contemporary Currents

While Cubist painters deconstructed objects and reassembled them from multiple viewpoints, Matisse simplifies without fracture. He keeps volumes intact but gently flattens them toward the surface. The glass bowl—a notoriously complex optical subject—becomes a lucid cylinder animated by a few chosen reflections. The sculpture remains solid yet stylized. In doing so, Matisse asserts a modernism grounded in harmony and legibility, proving that clarity can be as radical as complexity when achieved through fearless color and compositional economy.

Symbolic Readings

The painting invites symbolic associations without insisting upon them. Fish can suggest contemplation and an inner, self-contained world; a bouquet speaks of transience and arrangement; sculpture suggests permanence and the human form idealized. Together they map a triangle of time: the fleeting, the present, and the enduring. Yet Matisse resists allegory in the literary sense. His symbols are pictorial: orange against blue, curve against plane, movement against stasis. Meaning arises through looking, through the way the eye experiences these relations on the canvas.

The Intelligence of the Dark Ground

The decision to cast the room in deep darks is not merely dramatic; it is strategic. Darkness lets color sing. The fish could not burn so brightly in a pale interior; the bouquet’s reds and yellows would not pierce as clearly. The dark ground also compresses space and unifies diverse objects by bathing them in the same atmosphere. In such a context, even a pale sculpture becomes luminous, and the modest glow of reflected highlights feels intense. Matisse shows that darkness can be an active color, a setting that gives value to every note placed upon it.

Why the Painting Matters

“Fish tank in the room” matters because it demonstrates how a still life can become a complete philosophy of painting. With a handful of motifs—a bowl, a bouquet, a figure—Matisse distills problems of color contrast, surface versus depth, movement versus stasis, and sensation versus description. The result is neither an inventory of objects nor a display of technique; it is a living system in which each element supports the others. The painting models a way of seeing that is generous and exacting: generous in its delight in color and form, exacting in its refusal of clutter and anecdote.

Conclusion

This canvas from 1912 shows Matisse at ease with his means and ambitious in his aims. The fish glide within their glass world, the flowers hold their brief blaze, and the sculpture breathes a measured, stone-like rhythm. Against a quiet darkness, these presences create a conversation about looking—how painting can honor life in motion, life arranged, and life idealized, all on the same table. By tuning color and simplifying form, Matisse turns his studio into a small universe where harmony feels inevitable and where the eye learns, again, how to linger.