Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

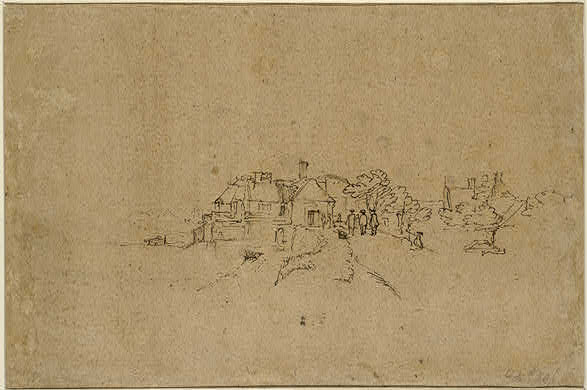

“Figures on the Anthoniesdijk Entering Houtewael” (1650) is a small, sparing drawing by Rembrandt that reads like a single deep breath taken at the edge of Amsterdam. Executed with a handful of quick, exact lines on toned paper, the sheet condenses a whole geography—dike, hamlet, copses of trees, and the long Dutch horizon—into a miniature that feels larger the longer you look. A few people appear at the hinge of a path, just where the Anthoniesdijk (St. Anthony’s Dike) bends and slips into the settlement of Houtewael. Nothing is theatrical; everything is quietly true. The drawing is not a spectacle of weather or architecture but a notation of lived space: how bodies, paths, buildings, and waterworks meet in a republic built from land reclaimed, measured, and continually tended.

A Place at the City’s Edge

The title locates us precisely. The Anthoniesdijk, running south of the medieval city, was one of the arteries where the urban fabric bled into polder fields. Houtewael (literally “wood marsh”) evokes a low, reclaimed terrain scattered with cottages, small orchards, and drains. In Dutch life this seam—the join of city and water-managed countryside—was where travel, trade, and the daily labor of keeping land dry converged. Rembrandt lived near such thresholds and returned to them often in drawings and prints. They mattered because they were the places where you could feel the city breathing: people going out to work, returning, meeting neighbors, stopping at a door for news. The drawing records that kind of moment.

Composition as a Statement of Scale

At first glance the sheet is mostly open paper. The cluster of buildings sits low and center-left, hedged by a few trees; a path curls toward them; to the right another stand of trees and a faint tower or gable balance the composition; beyond this little village, the page is almost empty. This emptiness is not neglect; it is a decision about scale. Rembrandt refuses to cramp the hamlet into a crowded vignette. He sets it in breath, allowing the pale field of the toned paper to do the work of sky, air, and distance. The vast negative space enlarges the few lines he does use, making their information ring.

The Path as Narrative

The most active mark on the sheet is the snaking path that strikes up from the foreground and bends into the door zone at center. It is sketched with a broken, searching stroke—just enough to indicate shallow ruts and a rise. That wavy line narrates the drawing. The figures—minute, but clearly social—walk with the track, and the viewer’s eye walks with them. This is where Rembrandt is at his most cinematic: he gives you a route to follow, an approach and an arrival. The drawing becomes not only a view of Houtewael but a remembered walk along the Anthoniesdijk, the way your feet learned it.

People as Punctuation

Rembrandt dots the path with a tiny procession: two or three figures mid-conversation, another paused at the threshold. They are little more than verticals with a flick for heads, yet they carry the drawing’s human temperature. Their presence punctuates the architecture and gives the place its reason for being. In much Dutch landscape of the period, figures can be decorative staffage; here they feel like neighbors. The artist reserves just enough detail—an arm lifted, a cloak’s angle—to declare intention and relation without fuss.

Architecture in Shorthand

The buildings are a triumph of economy. A hip roof is two meeting diagonals; a dormer becomes a notch with a dot; a chimney stands as a short stack of quick, darker strokes; a low wall or quay is a ruled line that steps once to catch a change in level. This shorthand trusts the viewer’s intelligence. Rembrandt tells you what each structure does more than what it looks like: this is where smoke means warmth, this where a door opens to the street, this where a wall holds back water or earth. There is a humility to the architecture—no grand façades, just usefully tangled accretions of rooms that push and settle as need dictates.

Trees as Anchors

Two small clumps of trees flank the village—one at the group of houses, the other set apart to the right. Their leaf masses are scribbled in rounded loops and scallops; trunks are a few vertical dashes. These trees anchor the hamlet against the sea of paper and stabilize the composition. But they also tell us about the place: shelter from wind, fruit, and perhaps the gentle noise that keeps a village from sounding empty. In a country with few hills, trees become the topography of a settlement; Rembrandt honors that function.

Toned Paper, Light, and Air

The sheet’s toned ground is crucial. It supplies the middle value of the entire drawing; Rembrandt’s pen then articulates the darks, while the untouched highlights are the paper’s own light. This triad—tone, line, reserve—creates an atmosphere you can feel. The village sits in a clear day, neither hot nor foggy; sky is present by virtue of not being described. The choice produces a kind of ethical clarity as well: the world is not dramatized, only attended to.

The Ethics of Leaving Out

One of the drawing’s most striking virtues is what it doesn’t say. There is no fussy cloud, no perfect fence, no reedy bank meticulously coiffed. The marsh edge is suggested by a few broken strokes; the bridge or stile is an angled smudge; distant buildings are faint echoes. This “leaving out” is not laziness; it is Rembrandt’s mature understanding that confidence in drawing allows the viewer to complete what matters. The omission lets thought move faster than description. It is also truer to how a walker sees: flashes and summaries, not inventories.

The Dike as Civic Sculpture

Although barely indicated, the dike is the drawing’s underlying protagonist. It is the reason the path exists, the reason the hamlet can sit this close to water. For Dutch eyes in 1650 a dike was not a romantic embankment but the republic’s great sculpture—earth shaped by many hands to secure life. Rembrandt’s choice to draw people “entering” Houtewael from the Anthoniesdijk is a civic statement. Settlement is a verb here, not a given. People continue to arrive, maintain, adjust. The drawing embodies that ethos of stewardship without preaching it.

Movement and Silence

The sheet is quiet, but not static. The path’s rhythm, the tilt of bodies, the suggestion of a breeze ruffling tree canopies—all whisper movement. At the same time the high ratio of untouched paper produces deep silence. That tension—between gentle motion and large quiet—is the drawing’s musical key. It is the mood of a morning when work begins, or late day when work thins, the hour when the road sounds of neighbor voices and the soft thud of feet on packed earth.

Time of Day and Season

Rembrandt gives no cast shadows strong enough to fix an hour, yet the overall tonality suggests clarity without glare—morning or late afternoon. The trees are in leaf, but not heavy, likely late spring or summer. These subtle seasonal cues help the hamlet feel lived rather than staged. They also harmonize with the medium: brown ink on a warm ground feels like weathering and sunlit dust.

The Viewer’s Stance

Where are we as viewers? Standing slightly below the hamlet, perhaps on a low bank or the dike itself, facing the village at a respectful distance. The path runs toward us but turns aside before it reaches our feet—an invitation to join without presuming closeness. That stance reflects Rembrandt’s social tact: he lets us witness a threshold without shoving us through it. The sheet behaves like a greeting rather than a tour.

Micro-Events

Spend time in the center and small incidents reveal themselves. A low cart or bench sits outside a door; a figure pauses at the corner; a child, maybe, hangs back. To the far right a distant tower or steeple establishes another settlement, implying a network of places stitched together by paths over wet ground. These micro-events enrich the narrative and confirm the trustworthiness of this tiny world.

Drawing as Field Note

The sheet feels like a field note made on a walk. Rembrandt probably carried a small portfolio and a pen, stopping when some turn of path and building arrangement pleased his eye. The drawing’s pace—quick setup, slower attention where figures gather, a few revisions in the path—bears that out. The blankness is not unfinished business; it is the rest of the day that remains to be filled by living. This is the kind of drawing that artists return to not for detail but for instruction in seeing.

Relation to Rembrandt’s Landscape Etchings

Seen beside the landscape etchings of the late 1640s and early 1650s—“A Peasant Carrying Milk Pales,” “An Arched Landscape with a Flock of Sheep,” “Landscape with a Cow Drinking”—this sheet speaks the same language of long horizons, humble architecture, and one anchoring human motif. The difference is extremity of economy. The etchings build gradations of tone across wider zones; this drawing leans entirely on line and paper. Yet the goal is identical: to build a believable, hospitable world from the fewest strokes possible.

A Social Reading

Because the title specifies “Figures … entering,” the drawing carries a social implication: movement into community. The cluster of people is not departing but arriving. The village is porous, open to the road; no gate, no wall; only the turn of a path and a door with a threshold worn by many crossings. In Rembrandt’s Amsterdam—cosmopolitan, argumentative, religiously mixed—this porosity resonated. The drawing’s small truth becomes a civic ideal: places where it is easy to come and go, to meet, to belong.

The Poetics of Distance

The faint city forms on the right register as memory more than fact. They are the place you started from or the place you will reach later. By making them so light, Rembrandt keeps the drawing emotionally balanced: the hamlet is not inferior to the city; it is simply nearer, more available to touch and speech. The poetics of distance in Dutch art often presents the far as dream. Here it is simply another neighborhood.

Materiality and Touch

The tangible pleasures of the sheet owe much to paper. The toned surface has a tooth that catches the pen just enough to give each stroke a slight chatter—visible in the tree scribbles and the broken path lines. When Rembrandt lifts the nib, a taper of ink remains at the end of a stroke like a breath at the conclusion of a word. These tiny signs of hand and tool keep the drawing honest. We are never tricked into forgetting we are looking at pen on paper, and that frankness is part of the work’s warmth.

Why So Much Emptiness?

Viewers new to Rembrandt’s drawings sometimes wonder why he leaves so much space unused. The answer here is twofold. First, emptiness is scale: it makes the cluster of marks feel remote and real. Second, emptiness is participation: it lets your imagination and bodily memory rush in to supply wind, smell, and step. The openness is an invitation to finish the picture with your own experience of paths and small towns. Few artists trust the viewer like this.

A Lesson in Seeing

For artists, the sheet is a lesson in editing. What are the minimum marks needed to plant a village believably in air? How much of a path must be drawn before a body knows where to walk? Which gestures—one head bowed, one hand lifted at a doorway—carry the most human information? Rembrandt answers by example: less than you think, if you place it where experience expects it.

Quiet Modernity

Despite its date, the drawing feels modern: asymmetrical composition, expansive negative space, a subject that is nothing more grand than arrival on a path. It anticipates later artists who would use emptiness and abbreviation to great effect in landscape and urban sketch. It also offers a counterweight to more theatrical baroque treatments of nature. Rembrandt’s modernity is ethical as much as formal: it is the refusal to overstate.

Conclusion

“Figures on the Anthoniesdijk Entering Houtewael” is a handful of strokes that holds a world. A path that remembers feet, cottages that promise warmth, trees that catch a little wind, neighbors at a door, a far skyline murmuring of other places—the drawing gathers these into a poised, breathable whole. It is not a panorama to be consumed but a threshold to be entered. Rembrandt’s genius here is restraint: he leaves room for the air of the Netherlands and for the viewer’s own walk to the village. The result is a picture that continues to feel true, not because it is detailed, but because it is hospitable.