Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Nice-Period Shift To Charcoal

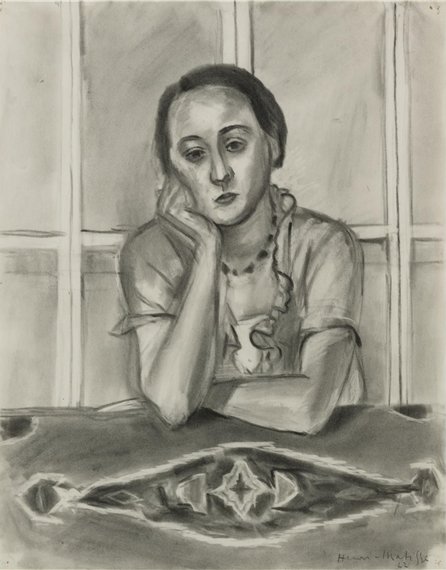

Henri Matisse made “Figure in Scutari Carpet” in 1922, at the heart of his Nice period, when he alternated between high-key interiors in oil and a parallel body of charcoal drawings. These drawings were not side notes; they were laboratories where he tested structure, value, and rhythm without the seductions of color. In Nice he had ready access to patterned textiles—screens, shawls, and oriental rugs—that he used as architectural devices inside small hotel rooms. The title’s “Scutari” refers to Üsküdar in Istanbul, a historical center for weaving; to a French audience of the 1920s, “Scutari carpet” signaled an Ottoman textile whose geometric ornaments carried an aura of exotic luxury. Matisse had collected and studied such carpets since the 1900s. By placing a pensive sitter behind a table draped with this pattern and in front of a gridded window, he binds three of his long-standing concerns—figure, ornament, and interior architecture—into a single, lucid system.

Composition As A T-Shaped Armature

The composition is built on a T-shaped armature. The horizontal of the table spans the lower third, while the sitter’s forearms form a second, softer bar that thickens the base. Rising from this is the axis of head and torso, held squarely at the center. The window muntins behind her provide a pale grid that stabilizes the whole and prevents the background from collapsing into an undifferentiated field. The figure’s left elbow (to our right) anchors the diagonal that draws from the forearm up to the hand supporting the cheek, continuing to the tilted oval of the head. This creates a contrapuntal rhythm against the rigid verticals of the window. The carpet’s diamond medallion, placed dead center on the table, gives the composition both a keystone and a mirror to the head above it. One sees a stack of ovals and diamonds—head and carpet motif—connected by the column of arms and torso. The structure is simple enough to read at once and subtle enough to sustain long looking.

The Scutari Carpet As Structural Counterpart

Matisse has always treated pattern as architecture rather than decoration. In the absence of color, the Scutari carpet must carry its weight by value and shape alone. He renders its medallion and corner devices with compressed charcoal, lifting or smudging to produce a velvet bloom that mimics pile. The central diamond floats like a dark pool, its edges softened so it reads as fabric rather than inlay. This weight at the bottom of the sheet balances the luminous oval of the head at the top, as if figure and carpet were equals in a conversation. The carpet’s bilateral symmetry also echoes the sitter’s frontal pose while the slight asymmetries of smudge keep the scene alive. Ornament here is not incident; it is the counterform that measures and steadies the human presence.

Value Design And The Breath Of Paper

Because charcoal offers only value, Matisse composes with a strict economy of lights and darks. The whitest whites belong to the paper left untouched in the window panes, on cheek ridge, and along a high accent on the forearm. The deepest tones gather in the carpet’s medallion, the necklace beads, the eye sockets, the seam under the jaw, and the table’s shadowed edge. Most of the figure lives in middle grays, brushed with the side of the stick or rubbed with a rag to create feathery halftones. This distribution gives the drawing an internal weather: light falls through a pale grid, settles softly on the sitter, and is absorbed by the carpet. The paper breathes between strokes, keeping air in the room. Where another draughtsman might have packed the background with detail, Matisse lets tone do the speaking. The result is spatial clarity without fuss.

Line As Calligraphy And Boundary

The contour of the head and arm is drawn with an elastic calligraphy. At the cheek the line thickens where the hand presses, then thins as it rounds the chin. The sleeve’s edge is not a single stroke but a cluster of lines, some dragged, some lightly lifted, which together suggest fabric fold without cataloging it. Around the necklace he drops small, decisive ovals of compressed charcoal that punctuate the soft passages and keep the center from going slack. The brows and eyes are simplified into a few curves; the nose is a quick ladder of planes; the mouth is a small, compact shape that turns at the corner. Everywhere, line works inside tone rather than on top of it. It declares boundary but refuses to imprison the forms it describes.

The Pose And The Psychology Of Inwardness

The pose is one Matisse returned to often in the early 1920s: elbow on table, head cradled by hand, body leaning slightly forward. It is a pose of attention turned inward rather than outward display. The gaze meets the viewer but seems to travel through them, as if the sitter’s thoughts have a longer horizon than the room permits. The necklace, blouse ruffle, and soft hair frame the face without asserting costume as subject. The drawing carries the atmosphere of a pause—the sort that occurs between reading and speaking, or after a piece of music ends and before the hands leave the instrument. This psychological interval is reinforced by the carpet’s still symmetry and the window’s quiet grid. Nothing in the room hurries; everything agrees to hold the moment.

The Window Grid And Modern Order

Behind the sitter, four large panes divided by muntins turn light into geometry. Matisse’s open-window oils fill such spaces with Mediterranean sea and sky; in charcoal he withholds scenery and keeps the panes milk-pale, letting the grid act as a modern armature. The verticals rhyme with the figure’s torso and with the downward fall of hair; the horizontals align with the table edge and shoulder line. Because the panes are the lightest values in the drawing, they push the figure forward without resorting to outline. The window thus supplies a double function: it is both a source of illumination and a pictorial scaffold. The choice is profoundly modern—less an illusion of place than an organization of the page.

Material Presence And The Tactility Of Charcoal

The medium itself is evident at every turn. You can feel the granularity where the stick snagged on paper tooth, the smear of a finger that softened a cheek plane, the swift eraser lift that reopened a highlight on the bowl of the shoulder. In the carpet, repeated press-and-twist motions grind pigment into a plush darkness, while a broad wipe creates the table’s quieter value. Matisse’s discipline is to let these processes remain visible, so that the making of the image coexists with the image. The honesty of touch prevents the drawing’s elegance from turning brittle. It is refined but never finicky, intimate without becoming precious.

Economy Of Description And The Intelligence Of Omission

The blouse’s ruffle is nothing more than a few zigzag shadows; the hairline is indicated but never filled; the hand that supports the head is simplified to a web of planes. Where detail would slow or clutter the composition, he omits it. Those omissions are strategic. They hold attention on relations—head to carpet, arm to table, face to window grid—rather than on gadgets of costume or the taxonomy of furniture. The viewer’s mind completes what is needed. Such trust in the spectator is central to Matisse’s mature practice and explains why the drawing remains light on its feet despite its sober mood.

Figure And Pattern In Mutual Definition

If you cover the carpet with your hand, the figure grows comparatively weightless; if you cover the figure, the carpet turns into a heraldic emblem floating in a field. The drawing’s true subject is their meeting. The medallion’s dark diamond is almost equal in width to the head above; the necklace’s beads acknowledge that correspondence in miniature; the forearm forms a bridge across which values travel from human to textile. Matisse is not content with the easy opposition of living flesh versus dead ornament. He stages a reciprocity: pattern lends the figure gravity; the figure lends the pattern life. The two become a single instrument tuned to a narrow range of grays.

Comparisons Within The 1922 Suite Of Drawings

Placed beside other Nice-period charcoals—women by windows, figures with mandolins, heads before patterned screens—“Figure in Scutari Carpet” stands out for its exact midline balance and for the way the textile asserts equal protagonism. Where a mandolin would introduce anecdote and curved contours, the Scutari carpet introduces symmetry and stillness. The difference matters. It moves the drawing closer to abstraction without losing the pressure of a living presence. In this sense the sheet anticipates the 1930s when Matisse’s portraits grow cleaner and his reliance on big, decisive shapes increases, culminating decades later in the paper cut-outs.

The Role Of Ornament In A Modern Portrait

Twentieth-century modernism often defined itself against ornament. Matisse took the opposite route: he absorbed ornament into structure. Here the carpet is not an ethnographic prop or an illustration of taste. It is a visual machine that allows him to distribute tones and build a stable stage for the head. The Scutari label, rather than a boast of exoticism, is a clue to the geometric intelligence that drew him to such textiles in the first place. He recognized that their medallions, lozenges, and palmettes were abstract shapes already speaking the language he wanted for painting. A portrait that can host such shapes without losing the person shows the maturity of that insight.

Light, Mood, And The Ethics Of Calm

The drawing’s mood is often described as introspective, but it is not heavy. The light is generous, even when modulated by soft shadows. The sitter’s mouth is firm yet relaxed; the eyes are thoughtful rather than sorrowful; the hand’s weight is real but not weary. Matisse was explicit about seeking an art of balance and serenity after the disruptions of the 1910s. This sheet exemplifies that ethic: it creates a chamber where attention can slow, where ornament and human presence reinforce rather than compete, and where light establishes a steady rhythm of breathing.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Time

The eye’s itinerary is consistent and renewing. One begins at the head—eyes, nose, mouth—drops along the supporting hand to the forearm, crosses the table’s edge to the carpet’s dark pool, follows its softened edges left and right, then rises up the opposite arm to return to the face. The window grid offers a brief rest for the gaze, and the cycle begins again. With each pass, subtleties emerge: the asymmetry between the two eyes, the compressed shadow under the necklace, the faint halo where hair meets pane. The drawing does not reveal itself in a single glance; it sustains a loop of attention that lengthens time rather than consuming it.

Craft Choices That Sustain The Whole

Several small craft decisions keep the composition coherent. The necklace’s beads are placed just low enough to anchor the center without competing with the mouth. The sleeve seam angles inward, gently guiding the gaze toward the face. The darkest tone of the carpet does not sit directly under the chin but slightly forward, avoiding a heavy stack of darks. The table’s front edge is softened and uneven, preventing it from overpowering the rest with a hard geometry. The panes of the window are not equal; the central ones are slightly wider, echoing the head’s breadth. These calibrations are easy to overlook and impossible to do without; they are the quiet engineering of the sheet.

Material Scale And The Intimacy Of Size

The drawing’s likely size—modest, domestic—helps produce intimacy. Charcoal at this scale allows the hand to move from elbow to fingertips in a single sweep, aligning gesture with form. The viewer stands at conversational distance from the sitter. Unlike grand portraits that assert social status through size, this sheet asserts closeness through scale. The Scutari carpet, a worldly object, is folded into this closeness; its pattern becomes not a distant luxury but an intimate texture that shares the table with the sitter’s arms.

What The Drawing Teaches About Looking

“Figure in Scutari Carpet” teaches a method of looking that Matisse practiced everywhere. First, perceive relations, not things: head to diamond, arm to table, light pane to dark medallion. Second, trust value before detail: the breath of paper equates to air. Third, allow ornament to carry structure. Fourth, accept economy as an instrument of tenderness; by not over-defining, you leave space for attention to rest. The drawing is an act of discipline that produces calm rather than severity, proof that clarity can be hospitable.

Conclusion: A Quiet Agreement Between Person, Pattern, And Light

In this 1922 charcoal, Matisse condenses his Nice-period ideals into a sober, resonant image. A central figure leans on a table; a Scutari carpet spreads its dark geometry below; a pale window grid rises behind. Charcoal’s limited means reveal maximal intelligence: value binds the planes, line breathes inside tone, ornament becomes architecture, and the sitter’s inwardness finds its rightful scale. Nothing clamors; everything agrees. The drawing endures because it models a balanced life of forms, where human presence and patterned beauty can share the same quiet air.