Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

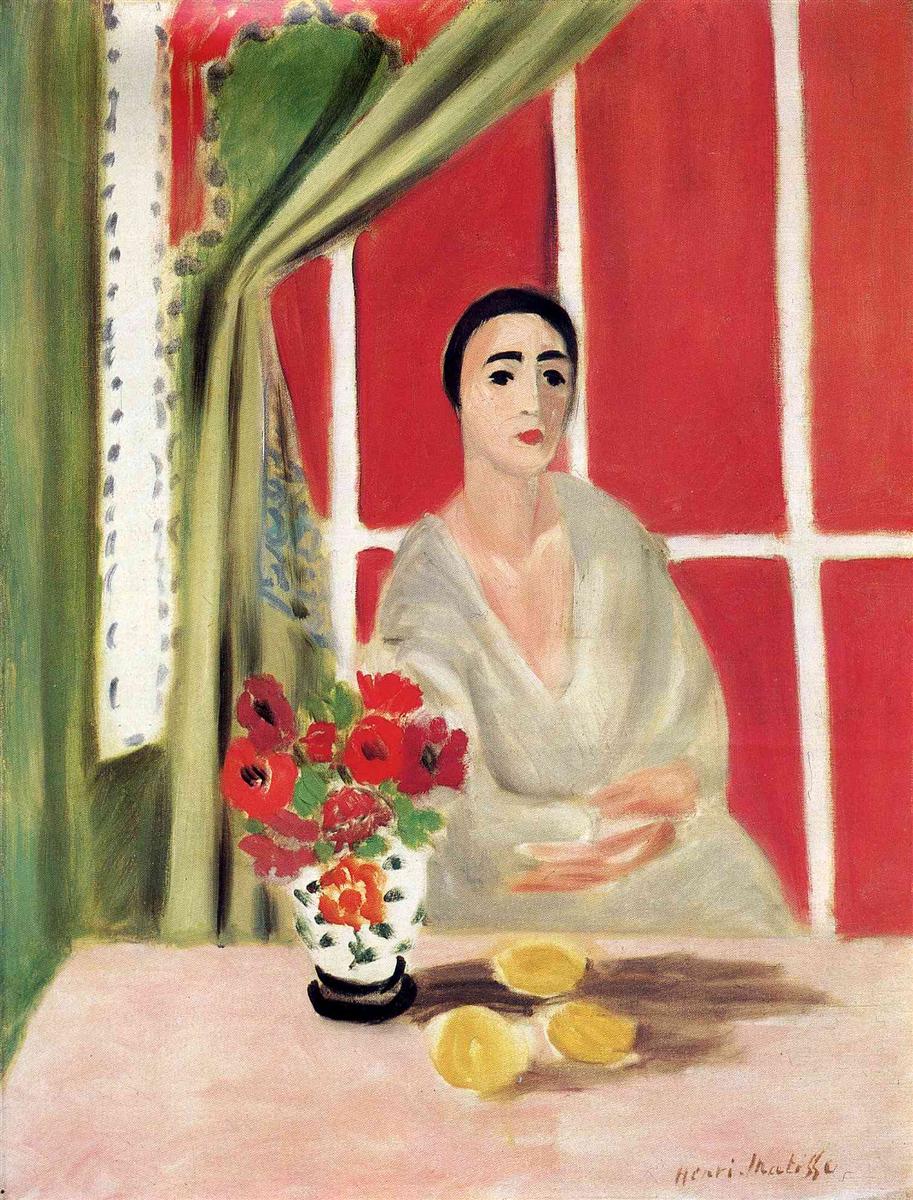

Henri Matisse’s “Figure at the Rideau Relevé” (1923) is a crystalline statement from his Nice period, when interiors, patterned textiles, flowers, and poised human presence fused into luminous harmonies. A woman in pale clothing sits at a table; to her left a vase of red blossoms glows, and three lemons rest on the tabletop like small suns. Behind her, a red wall is segmented by white bars, while a green curtain is drawn back—rideau relevé, the “curtain raised”—to open the composition like a stage. The painting is both intimate and theatrical, a study in how color can construct mood and how the smallest gestures can stabilize an entire room.

Historical Context and the Nice Period

Matisse began working in Nice in 1917 and returned repeatedly throughout the 1920s. The steady Mediterranean light encouraged him to paint from the model indoors, replacing the explosive dissonances of Fauvism with a poised modern classicism. Instead of deep perspective, he used layered planes—walls, screens, curtains—to compress space and bring figure and décor onto the same visual footing. In this world the curtain is not merely a prop; it is a device that controls revelation. “Figure at the Rideau Relevé,” painted in 1923 at the center of this development, turns the act of drawing a curtain into a compositional principle: opening the field to saturated color while holding back enough fabric to set a soft, cooling boundary.

Composition as Stagecraft

The composition reads like an interior stage. Two vertical curtains—one green with a pale patterned lining, one barely glimpsed at far left—frame a central wall of red divided by white uprights into panels. The table occupies the foreground as a shallow platform. The woman sits slightly to the right of center, her arms folded in front of her chest, elbows resting lightly. This triangular basket created by her forearms stabilizes the lower body and quietly echoes the peaked fold of the curtain above her head. The vase of flowers stands on the left edge of the table as counterweight to the figure, and the lemons, placed in a loose diagonal, lead our eyes back toward her.

The room’s geometry is simple and emphatic: verticals of curtains and wall bars; a horizontal table edge; a diagonal curtain sweep; the ellipse of the vase. These large shapes set the beat, allowing Matisse to place smaller accents—the flower heads, the lemons, the sitter’s lips and eyes—like notes within a measure.

The Drama of the Raised Curtain

The phrase rideau relevé is crucial to the painting’s idea. The curtain’s green arc, pinched high at the center and cascading toward the sides, announces that the scene is at once private and performed. It reveals the red wall the way a stage curtain reveals a set, and its scalloped edge adds a ceremonial flourish to an otherwise domestic room. At the same time, the curtain’s soft, cool green tempers the surrounding heat of red and pink, preventing the scene from becoming oppressive. With this single gesture Matisse dramatizes the act of looking: the picture feels as if it has just been opened for our gaze.

Color Climate: Heat and Cool in Balance

Color is the painting’s climate. A commanding red panel fills the background, segmented by white bars that seem to glow against it. In front of this warm field, the table is a gentle pink, bathed in light; the curtain is a green duet—leafy on the outer face, pale on the lining; the lemons and flowers deliver concentrated bursts of yellow and red. The woman’s robe is a cool, pearly gray that calms the heat behind her. Small accents calibrate the temperature: the black ellipse of the vase’s foot, the dark seeds in the blossoms, the near-black of the eyebrows and hair, and the faint coral of the lips.

Matisse never uses color as a mere label. Each hue is tuned for a role: the red wall gives the room its heartbeat; the green curtain provides shade and breath; the white bars and robe ventilate the surface; the flowers and lemons concentrate energy where needed. The result is equilibrium—sensuous yet clear, saturated yet breathable.

The Figure: Economy and Presence

Matisse’s figure drawing is famously economical. The head is an oval with a few decisive marks: strong arched brows, succinct lids, a short plane for the nose, and a compact mouth that anchors the face. Modeling is minimal—just a cool shadow along the cheek and under the chin—enough to tilt the head into believable space without sacrificing the painting’s planar clarity. The robe is built from broad, milky strokes that leave the canvas breathing; its openness and lightness make the body feel buoyant rather than heavy. The folded arms, simplified into luminous wedges, hold a small porcelain cup, a gesture that intensifies the sense of quiet attention.

The sitter’s presence is frank and stable. There is no melodrama, no storytelling psychology. She looks out with calm assurance, centered not by narrative but by the room’s order, as if her poise and the décor’s balance were two versions of the same idea.

Still Life as Counterpart

The bouquet and lemons are not accessories; they are protagonists. The flowers—scarlet, crimson, and coral with leafy greens—echo the wall behind and project forward like a warm chord struck near the viewer. Their container, a white vase dotted with floral motifs, repeats the picture’s main color constellation in miniature: red blossoms, green leaves, and white ground. The lemons on the tabletop—two halves and one whole—are placed just where the table’s light turns toward shadow, so they straddle warmth and coolness. Their citrine hue picks up the gold along the curtain’s lining and the hotter notes in the bouquet, creating a loop of yellow that helps secure the table to the wall.

Light Without Theatrical Shadow

The picture’s light is ambient, a hallmark of the Nice years. There is no raking glare; shadows are soft, cool, and transparent. The robe’s folds are suggested by slight temperature shifts, the table’s shadow by a smooth gradation from pink to a dove-gray band, the curtain’s depth by layers of olive and mint. This even illumination allows color to carry emotion. The red wall does the work of warmth and intensity; the green curtain and gray robe do the work of rest.

Space as Layered Planes

Matisse constructs space through layers rather than through deep perspective. Foreground: the table with vase and lemons; middle: the figure seated just behind the table edge; background: the red wall segmented by white bars and framed by curtains. These planes lie close to each other, keeping the viewer near. Overlaps and color intervals, not vanishing points, create the sense of distance. The shallow depth places emphasis on relational clarity—how red converses with green, how white ventilates both, how pink and yellow knit the room.

Pattern and the Democracy of Surfaces

A dotted lining peeks from the curtain’s inner edge; the vase repeats flowers on its own skin; the wall is built from blocks of color rather than literal paneling. Each of these elements has equal dignity. Matisse’s modernism is decorative in the highest sense: the human figure is not more “important” than a curtain fold if that fold carries rhythmic necessity. What the eye enjoys, the mind can trust; beauty is distributed, not hierarchical.

Rhythm, Interval, and the Tempo of Looking

The painting’s rhythm arises from repeating shapes and measured distances. Vertical bars of white divide the red ground into beats; the curtain’s scallop adds a gentle off-beat; the flowers cluster into rounded pulses; the lemons mark a slower metronome across the table; the folded arms hold a long, quiet note at the center. This orchestrated tempo encourages slow looking. The eye moves from red to green, from bouquet to face, from lemons to hands, never snagging on detail, always returning to the whole.

Brushwork and the Trace of the Hand

Up close, the surface reveals a varied touch. The red ground is laid in with even, slightly open strokes that allow the weave to glimmer. The curtain’s green is pulled in long, elastic sweeps whose edges feather into the light; at the lining, smaller scalloped marks punctuate the border. The bouquet is a cluster of loaded dabs; petals are formed by the pressure and lift of the brush, not by drawing. The lemons are simple, creamy ovals, their highlights laid in with a single turn of a small brush. On the figure, paint thins to a translucent veil that lets underlayers warm the edges of flesh and robe. This diversity of touch keeps the picture alive without disrupting its serenity.

Dialogues with Other Works of 1923

Compared with Matisse’s standing and seated odalisques of the same year, “Figure at the Rideau Relevé” is less theatrical and more architectural. The figure shares space with a bouquet and fruit rather than with instruments or carved screens. Yet the language is the same: shallow layered planes, ambient light, decisive color. The red wall recalls the rich grounds of many Nice interiors; the green curtain echoes the striped and checked textiles he loved to stage; the lemons link this painting to his still-life explorations, where fruit and flowers become color engines rather than symbolic props.

A Reading of Meaning Through Form

What does the painting mean beyond its immediate beauty? The title’s emphasis on the curtain suggests a moment of revelation or readiness. Perhaps the model has just entered; perhaps she’s been there, waiting to be seen, and the curtain’s lift simply acknowledges that encounter. The red field—intense but pacified by white bars—serves as a metaphor for concentrated emotion disciplined by structure. The bouquet’s freshness and the lemons’ brightness speak to the cultivated pleasures of domestic life. In sum, the painting proposes an ethic of attention: order your room, open your curtain, place a few living things within reach, and sit with composure. In such a climate, presence itself becomes meaningful.

How to Look, Slowly

Begin at the vase and let the scarlet blossoms set your tempo. Follow the green leaves to the curtain’s line and climb its arc to the top hinge where the rideau is gathered. Cross the white bar to the sitter’s face, noticing how a handful of dark notes—brows, eyes, lips—carry the whole expression. Drift down the robe’s pearly planes to the folded arms and tiny cup. Slip forward to the lemons, reading their highlights as the same light that brightens the wall’s bars. Slide along the table’s edge to the left and back to the vase. With each circuit the painting’s logic becomes clearer: red and green breathe in balance; white and gray ventilate; small accents of yellow and black hold the chord in tune.

Conclusion

“Figure at the Rideau Relevé” crystallizes Matisse’s Nice-period conviction that color can think and ornament can structure feeling. A raised curtain reveals a red field; a woman sits in pale calm; flowers flare; lemons glow; the table holds steady. No part is expendable, and none clamors for dominance. The painting’s serenity is earned through exquisite calibration—of temperature, interval, edge, and touch. Nearly a century later it still offers what Matisse hoped for: a space of restful clarity where the eye lingers, the mind quiets, and the world feels, for a moment, ideally arranged.