Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

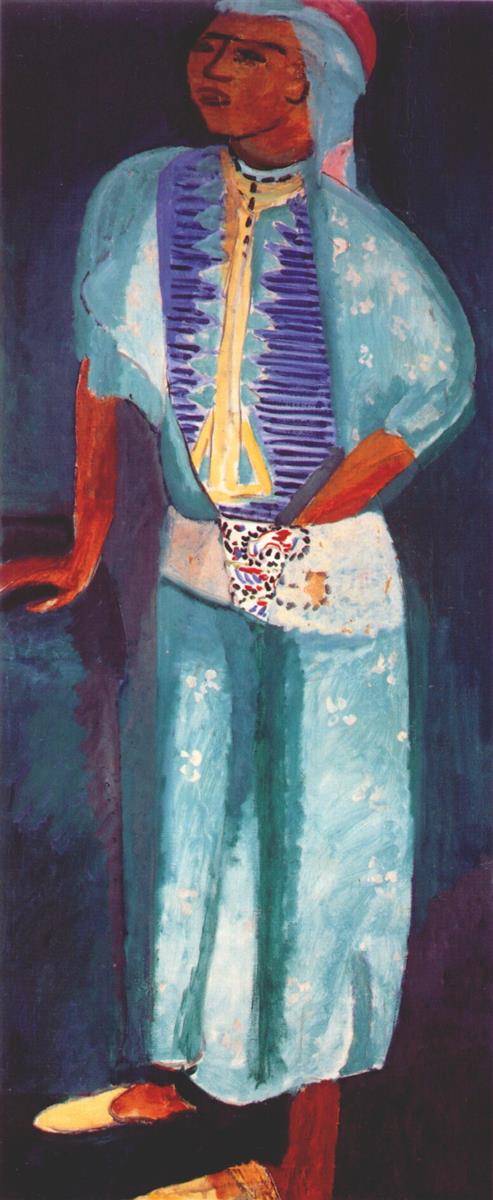

Henri Matisse’s “Fatma” (1912) belongs to the cluster of portraits he made during his Moroccan sojourn, where the climate of light, the severity of architecture, and the hum of patterned textiles reoriented his painting. In this vertical canvas, a young woman stands at ease, one hand at her sash and the other resting against a ledge. She wears a long turquoise robe lightly strewn with pale floral marks, a violet-plaited vest trimmed with yellow, and a pink head covering that slips behind the neck. The ground around her is a deep, breathing blue that reads as wall and shadow at once. The figure occupies nearly the entire height of the narrow format and seems to press gently against the edges, as if color were a room she inhabits rather than a backdrop. The portrait is concise, dignified, and modern, translating the sitter’s presence into an architecture of hue, contour, and rhythm.

A First Look at the Image

The painting introduces its subject without anecdote. There are no props beyond a faint ledge at the left edge, no narrative activity, no descriptive interior. The blue field is slightly darker behind the head and arm, lighter near the robe’s hem, and streaked with brushwork that keeps the surface alive. The robe is a cool, watery turquoise lifted by scattered white blossoms; the vest is a ladder of violet bars framed by a lemon-yellow placket that climbs toward the neck; the sash around the waist is patterned cream with red and blue flecks, a small echo of the textile world outside the canvas. The face is built of warm ochres and rose-browns, set off by emphatic brows and a firm nose; the hands and bare forearm are rendered with the same warmth, tying skin into the garment’s cooler climate. Everything is simplified but nothing is careless. The portrait is a calibrated set of decisions designed to let the person speak through color.

The Vertical Format as Structure

The painting’s narrow, nearly figure-width format is not an eccentricity; it is a structural choice that shapes how the body reads. By compressing the flanks, Matisse makes the figure a column whose proportions echo the minarets and doorways he observed in Tangier. The stance—slightly leaning, weight dropped into the back leg, front foot pointed outward—activates the entire height. The format also enforces a conversation between the garment’s long verticals and the canvas itself. The violet bars of the vest rise like another set of planks inside the frame, while the robe’s seams drop in pale green lines that parallel the edges. The result is an orchestration of upward thrusts and downward falls that lends the figure an architectural steadiness, as if she were built into the space rather than merely placed there.

Color as the Engine of Portraiture

Matisse builds likeness through color relationships rather than sculptural modeling. The cool turquoise robe does not wrap the body in shadow and highlight; instead, it exists as a soft plane whose temperature is adjusted by adjacent hues. Where the robe meets the deep blue of the background, both colors shift slightly, each making the other more itself. The violet of the vest sits between the cool robe and the warm skin, acting as a mediator and a musical middle register. The yellow placket is a single vertical flare that draws the eye to the center and up to the face; its intensity is carefully rationed so it leads without shouting. Punctual notes—the pink of the head covering, the warm ochre of the slippers, the dotted cream of the sash—create a rhythm of reprises that guides looking from head to foot and back again. Color is not decoration; it is portraiture’s grammar.

Drawing with the Brush

Contour is the decisive instrument in this painting. The line that defines the cheek and jaw is not a thin outline but a calligraphic stroke that varies in thickness and speed; the arm’s outer edge is trimmed with a dark run that presses the figure forward; the nose and brows are set in with assertive marks that stop just shy of caricature. Because these contours are painted, they carry weight and temperature; they are not separate from the color fields they describe. Within forms, Matisse lets the brush ride loosely, as in the robe’s interior where strokes slant and splay, creating a living fabric rather than a diagram of folds. Even the tiny white flowers are laid as quick touches, enough to break the turquoise into lively intervals without collapsing into pattern for its own sake.

Light Constructed by Adjacency

The painting’s illumination is not staged with directional highlights or cast shadows. Instead, light is created by adjacency—cool beside warm, light beside dark, translucent beside opaque. The face glows because its warm ochres sit against the cool headdress and the dusky blue; the arm brightens where it crosses the darker wall; the vest’s yellow seems luminous because it is hugged by violet bars. This strategy of illumination keeps the surface unified and the atmosphere convincing without sacrificing the painting’s flatness. The viewer senses a specific air and hour, but the picture never pretends to the illusionism of a window.

Pattern, Textile, and the Discipline of Ornament

Morocco supplied Matisse with an abundant vocabulary of textiles, but in “Fatma” he uses that vocabulary with restraint. The robe’s pale blossoms are lightly scattered, the sash carries a small, densely worked motif, and the vest’s bars keep time like a musical staff. This discipline serves two functions. It prevents the picture from tipping into ethnographic inventory, and it binds figure and field through repeated rhythms. The small pale marks on the robe rhyme with the lighter strokes in the background; the patterned sash echoes the dotted accents elsewhere; the vertical bars align with the canvas and stage the ascent toward the face. Ornament is structural, not illustrative.

Pose, Gesture, and Psychological Temperature

The stance reads as both informal and self-possessed. One hand tucks into the sash, introducing a casual asymmetry; the other rests on the ledge at left, anchoring the figure in space and supplying a diagonal that checks the painting’s many verticals. The tilt of the head is slight, with the gaze turned to the left as if attending to a sound outside the frame. This oblique attention deepens the sense of presence without forcing narrative. The face is quiet but not passive; the eyes are simplified yet alert; the mouth settles into a firm, closed line. Color reinforces this psychological temperature. The cool robe and ground stabilize the composition, while warm skin notes keep it human. The portrait is calm, not soft; it is open, not vulnerable.

The Ethics of Simplification

Matisse’s simplification is not a denial of individuality but a method for protecting it. By removing descriptive embellishment, he gives the sitter’s bearing and gaze a clear path to the viewer. There are no objects that invite curiosity about lifestyle or social habit; there is no setting to catalog; there is only the person integrated into a climate of color. In an era when European images of North Africa frequently exoticized or dramatized, this economy matters. It resists sensational spectacle and offers instead an encounter grounded in attentiveness and respect.

Relation to the Moroccan Cycle

“Fatma” speaks to a constellation of works from 1912–13. Compared with the cross-legged seated “Fatma” and the portraits of Zorah, this canvas is more vertical, more architectural, and more given to long chromatic runs. The same reliance on saturated grounds, decisive contours, and tuned complements persists, but here the emphasis shifts from icon-like frontal composure to a poised, standing presence. It also foreshadows the way Matisse will soon organize complex studio interiors—such as “The Pink Studio”—through simple, powerful axes of color. Morocco didn’t merely provide motifs; it taught him how planes and intervals could carry the whole weight of representation.

Space Without Perspective

Depth in the painting is felt rather than calculated. The ledge at left provides a single cue; the darker wedge behind the lower robe suggests a receding corner; otherwise, space is a continuous field of blue in which the figure is fully legible. This compressed depth is a virtue, not a deficit. It keeps the viewer close to the subject, prevents the portrait from becoming an anecdotal scene, and allows color to do the work of atmosphere. The surface remains a painting first, a depiction second.

Surface, Paint, and the Trace of Decisions

The skin of the picture reveals the order of its making. The blue field, laid with broader, semi-transparent strokes, shows changes in pressure and direction that catch on the canvas weave. Over that field, the robe arrives as a large cool mass, later broken by blossoms and seams. The vest’s violet bars are drawn with a smaller brush, each bar a single assertive pass. The yellow placket is reserved for late in the process, as if Matisse waited to tune that note only after the other registers were fixed. Small corrections are left visible, especially where the robe meets the ground or the slipper touches the edge. These traces keep the image human and present; they let the viewer witness not just the result but the thinking.

The Face as Sign and Presence

Matisse uses the fewest possible marks to carry the face. Eyebrows are long, dark accents; the nose is a vertical with a brief lateral flare; the lips are a compact shape keyed darker than surrounding skin; the cheek is a wider plane of warm color that turns only slightly into shadow under the eye. This economy achieves a double effect. From a distance, the face reads instantly—serious, attentive, poised. Up close, the differences in temperature and the soft scumbles of ochre and rose give it life. The balance between sign and presence is one of the painting’s quiet triumphs.

The Dialogue of Complementaries

The picture’s chromatic engine is the play between cool turquoise and warm reds and ochres. Rather than pitch these complements at their loudest, Matisse lowers the volume. The robe is milked with white; the skin is moderated with umbers; the background blue leans toward indigo rather than electric cyan. Because the complements are softened, their meeting produces harmony rather than glare. The yellow placket, set within a field of violet, adds a secondary complementary pair that energizes the center without destabilizing the whole. This balanced complementarity is why the painting feels both clear and restful.

Cultural Specificity Without Stereotype

Clothing cues—robe, head covering, patterned sash—locate the sitter in North Africa, but Matisse refuses to turn cultural specificity into spectacle. No props signal “otherness”; no behavior is staged for an outside gaze. The portrait honors difference by taking it seriously, translating it into form rather than costume. The sitter is neither anonymized nor exoticized; she is present. This approach resonates today because it models a way to look across cultures with curiosity and restraint, allowing the person to eclipse the picturesque.

Influence and Afterlife

The lessons of “Fatma” reach beyond its moment. Designers recognize the authority of a dominant field color activated by a few tuned accents. Photographers see how posture and negative space can carry personality without a set or props. Painters find a guide for using contour as an expressive instrument while keeping surfaces open and breathable. The portrait also foreshadows Matisse’s late cut-outs: long verticals, simplified limbs, and flat yet resonant color planes that tell a story of presence in the fewest possible shapes.

Why the Painting Still Feels New

The image remains fresh because its solutions are permanent rather than fashionable. The format is daring but logical; the palette is limited but deep; the drawing is assertive but tender. Above all, the portrait offers a kind of attention that is increasingly rare: an attention that neither consumes nor explains, but simply witnesses. “Fatma” invites looking that is patient and reciprocal; it gives back as much focus as it receives.

Conclusion

“Fatma” distills the discoveries of Matisse’s Moroccan journey into a single figure who stands in a climate of blue and holds her own. Color acts as architecture, contour as voice, pattern as rhythm. Space is shallow, presence is deep. By practicing an ethics of simplification, Matisse achieves not a general type but a particular person rendered with clarity and respect. The painting shows how modern portraiture can be at once decorative and grave, reduced and rich, immediate and inexhaustible. In this slender vertical world, a woman becomes a column of quiet light.