Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

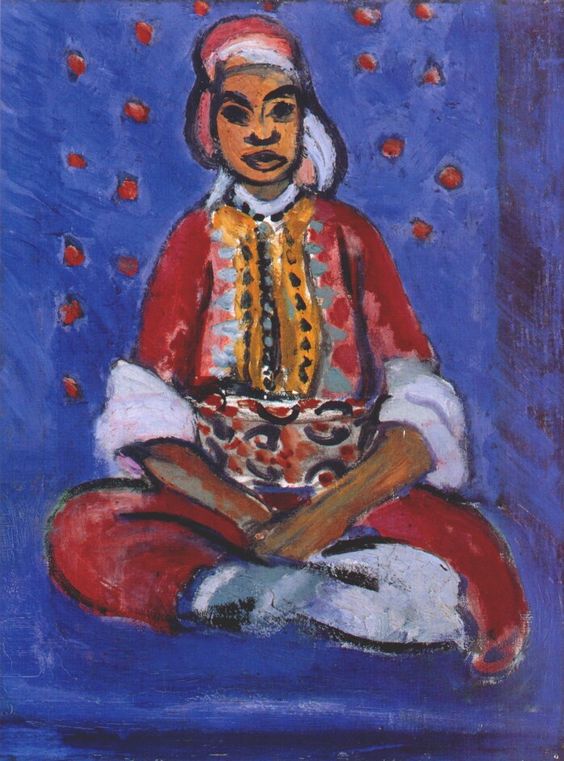

Henri Matisse’s “Fatma” (1912) is one of the most succinct portraits to emerge from the painter’s North African sojourn, a period that recalibrated his approach to color, contour, and the very idea of likeness. The sitter wears a richly red garment trimmed with white cuffs and a patterned sash, crowned by a soft cap; she sits cross-legged on a saturated blue field sprinkled with small red discs. Everything is distilled: the oval face bordered by a dark headscarf, the almond eyes marked by emphatic strokes, the long, steady nose, the quiet lips, the decisive outline of hands folded across the lap. Little is described, yet the image feels fully present. In this canvas Matisse rethinks portraiture as an encounter between person and color climate, between ornamental rhythm and human dignity. What might have been an ethnographic “type” becomes an icon of poise.

The Moroccan Context and the Meaning of a Name

Painted during Matisse’s 1912 trip to Morocco, the picture reflects his contact with the clear light, bold textiles, and architectural planar spaces of Tangier. “Fatma” is a widespread North African name; in French colonial usage it was sometimes generalized for Muslim women. Matisse’s picture resists such reduction by granting the sitter a commanding centrality and by stripping away anecdote. There is no marketplace, no interior scene layered with props, no picturesque accessories—only the person held upright by color. He translates the strong geometries and surface values he admired in Islamic ornament into the terms of modern portraiture, while avoiding the voyeurism that often colored European depictions of North Africa. The painting does not look at “customs”; it looks at a woman.

An Architecture of Blue and Red

The first shock is chromatic. A field of ultramarine, weighted with touches of violet and cobalt, forms the stage upon which the figure appears. Against this cool expanse, the garment’s vermilion erupts like a contained flame. The red is not a single note: it ranges from orange-warm sleeves to deeper carmine shadows, with white cuffs and collar intensifying the contrast. A sash, flecked with black and cream, mediates between torso and lap; its pattern joins the dots that sprinkle the ground, binding person and setting into a single decorative continuum. Matisse’s complementary pairing of red and blue is deliberate and structural: blue opens space and quiets the eye, red concentrates energy and directs attention. The effect is monumental without heaviness.

Composition and the Frontal Icon

The sitter is placed dead center, symmetrically framed by the blue wall and floor that merge into one plane. Cross-legged, she forms a stable triangle whose apex is the cap and whose base is the loop of legs and slippers. This triangular pose, both frontal and grounded, evokes the composure of devotional painting and the direct address of a bust in a niche. Matisse renounces tricks of depth and instead sorts the surface into stacked bands: cap and face; jacket and sash; legs and slippers. The result is a portrait that reads at a glance and continues to yield smaller rhythms to patient looking.

Drawing with the Brush: Contour as Statement

A key to the picture’s force lies in Matisse’s treatment of contour. Using a near-black mixture laid down with a loaded brush, he draws the outline of face, turban, shoulders, and hands as if writing them. The line is elastic—thickening at the jaw, thinning around the lips, tightening to a point around the eyes. Because these contours are painted, not penciled, they participate in the color rather than floating above it. They are declarations, not fences; by their speed and certainty they grant the sitter a calm authority. Volume is implied by small shifts of temperature within the red garment and by the junction of forms, not by academic modeling. The drawing says only what is essential—and thus says it unmistakably.

Pattern as a Language of Respect

Matisse had studied textiles and ceramics in North Africa with palpable fascination. In “Fatma,” pattern is not a backdrop of exoticism; it is a language for dignity. The tiny red discs that punctuate the blue field suggest embroidery, stars, or pomegranate seeds, but they are most importantly measures in a visual music that continues across the person. The patterned sash is stated with a few cursive marks, echoing the field and preventing the garment from hardening into a flat block. Ornament and body share a rhythm, as if the sitter’s presence modulated the room. This is one of the picture’s quiet achievements: decoration becomes a sign of shared space rather than a spectacle for distant eyes.

Hands, Sleeves, and the Ethics of Gesture

Portraits often hinge on hands. Here they are simplified to long ovals and wedges, crossed in the lap, fingers only lightly suggested. The hands are not passive; they organize the lower third of the canvas, their tawny color bridging the hot red of the trousers and the cool blue that creeps between the legs. The white cuffs—thick cuffs of paint as well as of fabric—frame the wrists like parentheses, emphasizing composure. Matisse refuses to prettify the gesture or to offer narrative props; the sitter’s own posture suffices. By subtracting anecdote, he returns agency to the person.

Light Constructed by Adjacency

There is no single lamp or window; the atmosphere is created by how colors meet. The red jacket brightens where it borders white; it deepens where it abuts the blue. The face gains volume not from shaded cheeks but from the way ochres and siennas sit beside the dark outlines of eyebrows and lips. The cap, a pale pink with whitish sides, seems to catch light because adjacent blues press it forward. Glow is a property of intervals, not of mimicked sunlight. This strategy keeps the surface unified; the painting never “breaks character” by staging a theatrical light effect.

The Face: Sign and Presence

Matisse compresses the face into a few potent marks. The almond eyes are elongated strokes nested in darker arcs, imparting both watchfulness and serenity. The brows are swift accents; the nose is laid in with a single, straight vector that stops before it becomes descriptive. The mouth is dark, slightly fulsome, mounted on a firm chin. These decisions locate the sitter culturally and personally without caricature. The mask-like clarity owes something to the artist’s engagement with African sculpture and Byzantine icons, but its effect is not to dehumanize; it is to concentrate. The face reads across a room and rewards close inspection, where tiny modulations of warm and cool reveal a skin that breathes.

Space Without Perspective

The blue field behind and beneath the sitter resists division into wall and floor. A slight darkening near the lower edge hints at ground, but Matisse declines to tether the figure to a conventional room. Instead, space is a chromatic climate. The red discs floating across the same blue that supports the body corrode the boundary between background and foreground. To a viewer accustomed to photographic logic, this may feel ambiguous; to Matisse it is the very point. The sitter occupies not a measurable box, but a field of color that matches her self-possession.

Comparisons within the Moroccan Cycle

“Fatma” converses with related canvases from the same journey. Portraits of Zorah, harem interiors, and scenes at the casbah likewise employ saturated grounds, dark contours, and a few decisive patterns. Yet “Fatma” is among the most distilled: no window, no balcony, no carpet view into the city. Its closest kin are the portraits where a single model sits before an intensely colored textile. The distinctions matter. By choosing near-monochrome blue for the ground and limiting descriptive pattern to small dots and a sash, Matisse doubles down on the person. It is as if travel, rather than expanding the inventory of motifs, taught him what he could live without.

Material Surface and the Order of Decisions

The painting’s tactility repays attention. In the blue ground, scumbled layers catch on the canvas weave, leaving streaks that suggest a worn textile. The red garment is painted more densely, its edges occasionally trimmed by a return stroke of darker paint to keep the silhouette crisp. White cuffs and collar are laid with opaque body color, almost impastoed, communicating volume with the bluntness of plaster. The headscarf’s shadow is a soft violet, a cooling note that tucks the face into space. You can read the order of decisions—ground first, then the big red of the garment, then the head and hands, and, late in the process, the dotted pattern fusing figure and field. That sequence gives the portrait its odd inevitability, as if it discovered itself.

Cultural Sensitivity and the Avoidance of Exoticism

Any early twentieth-century European image of North Africa sits in the shadow of Orientalism. What distinguishes “Fatma” is the way Matisse refuses the script. There is no eroticized odalisque, no garnish of weapons or hookahs, no “view” of local color as tourist spectacle. The sitter is dressed richly but modestly; her gaze is steady; her body occupies the center with the assurance of an equal. By making the background a monochrome abstraction rather than a catalog of setting, Matisse undercuts the temptation to treat culture as decoration and allows the portrait to exist primarily as a meeting between viewer and person.

Rhythm, Repetition, and Decorative Unity

A portrait that leans on pattern risks dispersing attention. Matisse knits the picture by establishing a small set of repeating marks and letting them circulate. The dots on the blue field echo the rondels and loops in the sash; the white cuffs rhyme with the white collar and the pale elements of the cap; the warm ochre in the vest’s placket reappears, cooled, on the hands and face. Even the crossed legs mirror the triangular bodice, doubling the basic geometry. Because the vocabulary is limited, every occurrence strengthens unity rather than diluting it.

The Psychology of Color and Poise

Blue dominates, and with it a calm that tempers the energy of red. Yet this is not a cold blue; streaks of violet, small islands of warmer cobalt, and the pulse of red dots keep it alive. The palette creates a psychological space of attention without agitation. The sitter’s poise intensifies that atmosphere. Eyes level, head slightly inclined, she seems self-contained, available to the viewer’s gaze but not bent by it. The painting becomes a study in composure—not stiffness, but inward steadiness manifested as pure form.

Lessons in Looking and Making

From “Fatma” a set of practical lessons emerges. A compelling portrait can be built from a reduced palette if the intervals between colors are clear and musical. Contour painted with conviction can carry likeness more efficiently than prolonged shading. Pattern can honor a sitter when it is structural rather than descriptive—when it supports the composition rather than treating culture as costume. Depth can be replaced by color climate without losing presence. Above all, omission is not emptiness; it is an ethics of attention that grants the viewer and the sitter a larger share of space.

Why the Painting Feels Contemporary

A century on, the work’s modernity is undimmed. Designers will recognize the power of a dominant field color punctuated by a complementary accent; photographers will appreciate how separation is achieved by temperature rather than focus; painters will see a manifesto for economy and clarity. Viewers unused to early modern art may be surprised by the portrait’s immediacy: despite the stylization, the encounter feels direct. That freshness comes from Matisse’s refusal to let technique eclipse presence. The painting is a device for looking well.

Conclusion

“Fatma” condenses the discoveries of Matisse’s Moroccan period into a single, resonant image. A blue climate holds a red-clad figure; black contours speak with calligraphic authority; modest pattern ties person to place; the face is both sign and individual. The picture declines exotic anecdote in favor of an art of essentials—an art that finds dignity in simplification and poise in color. Standing before it, one senses not only the brilliance of a painter at the height of his powers, but also the quiet self-possession of a sitter who holds her ground within a field bright with looking.