Image source: artvee.com

Historical and Biographical Context

In the autumn of 1888, Vincent van Gogh arrived in Arles, Provence, driven by a longing for northern France’s vivid light and the promise of creative renewal. Having endured a turbulent year in Paris, Van Gogh was eager to immerse himself in the region’s rural rhythms. He established his “Yellow House” on the Place Lamartine and soon became fascinated by local farm life. “Farmhouse in Provence,” executed in October 1888, belongs to this period of intense productivity: between August and November he completed over a hundred canvases. Santé and pigment were never far from his mind, yet the farmhouse paintings reveal not only his formal innovations but also his deep empathy for Provençal culture. In letters to his brother Theo, Van Gogh celebrated the humble dwellings and working fields as embodiments of honest labor, seeing in stone walls and tiled roofs a kind of human dignity he wished to honor on canvas.

The Setting: House, Fields, and Provençal Landscape

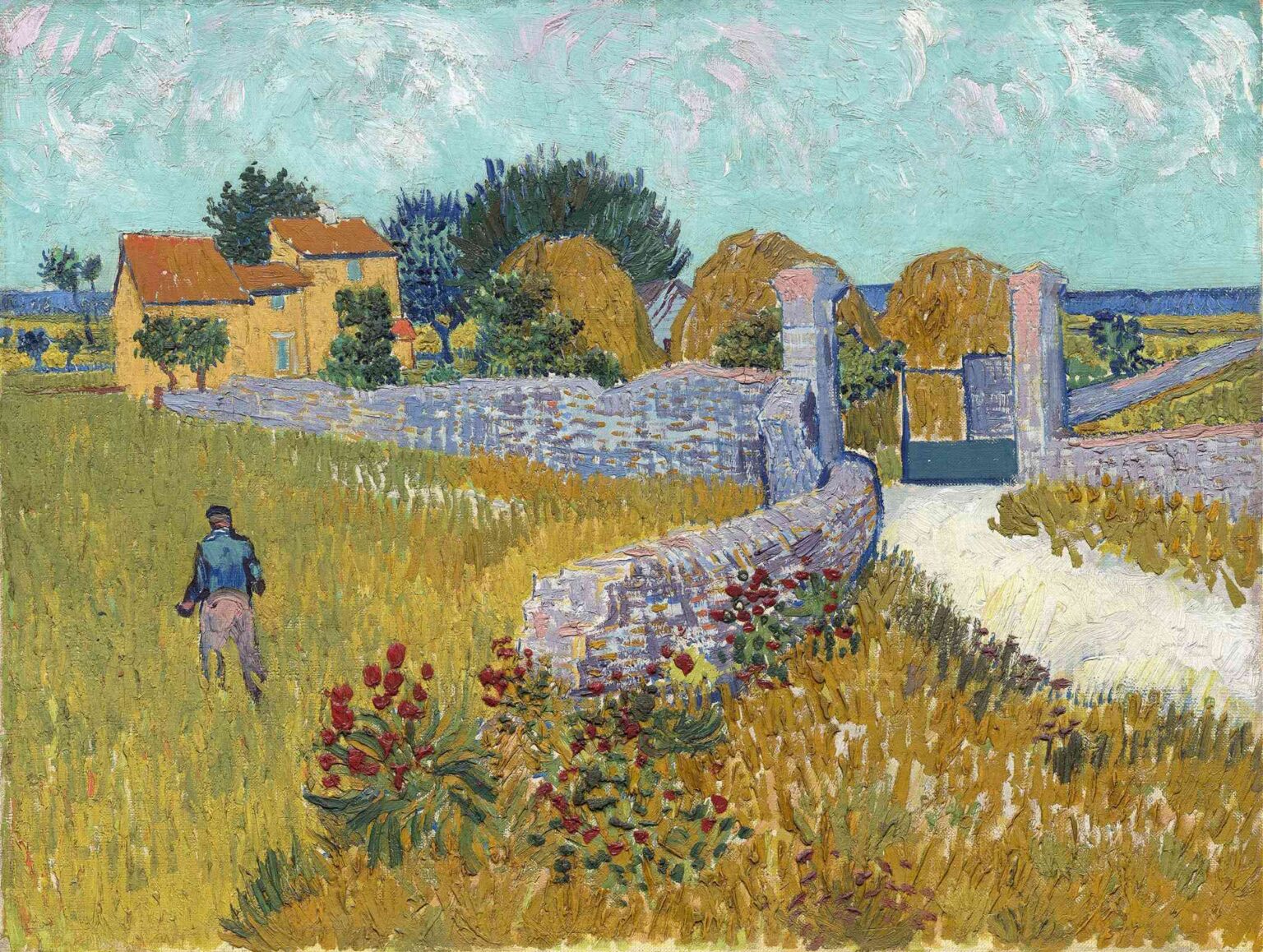

“Farmhouse in Provence” depicts a modest stone dwelling nestled amid ripening wheat and olive groves. The structure’s ochre walls and terra-cotta roof tiles gleam in the midday sun, contrasting sharply with the deep green cypresses that flank it. A low stone wall curves gently around the field in the foreground, guiding the viewer’s eye toward the open gate. Beyond, a patchwork of fields recedes to a cobalt horizon. Van Gogh’s choice of vantage point—slightly elevated and off-center—allows him to balance architectural solidity with the fluid energy of the surrounding landscape. Rather than portraying the farmhouse as isolated, he integrates it into its environment, celebrating the symbiotic relationship between human habitation and nature’s cycles.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Van Gogh employs a diagonal schema to animate the scene. The stone wall in the foreground cuts across the canvas from lower left to center right, creating depth and suggesting a path into the picture. The farmhouse sits just left of center, its rectangular form grounded by the vivid horizontal line of the gate’s lintel. Behind it, the horizon line sits at mid-canvas, dividing earth and sky almost equally. Vertical accents—the cypress trunks and the farmhouse chimney—punctuate this layout, preventing stagnation. The overall effect is rhythmic: our gaze moves from the grain field to the roof’s ridge, then down along the olive-olive grove line, and back across the field. Van Gogh thus transforms a static rural scene into a dynamic visual journey.

Palette and Chromatic Effects

Van Gogh’s palette in “Farmhouse in Provence” is emblematic of his Arles period: high-key yellows, warm ochres, and verdant greens dominate, while accents of cobalt blue and lavender enliven the sky. The wheat field shimmers in buttery yellow, applied in short, directional strokes that mimic the stalks’ verticality. The farmhouse walls, painted in orange-tinged yellow, catch the sunlight, whereas shadows on the northern facade reveal cooler tones—pale mauve and muted green. Cypress foliage is rendered in deep emerald, punctuated by bright highlights where leaves catch the light. The contrasting warmth of earth and coolness of vegetation underscores the painting’s emotional resonance: the world is simultaneously radiant and serene.

Light, Atmosphere, and Seasonal Resonance

Van Gogh captures a late-summer afternoon in Provence, when the sun hovers at its zenith and shadows are minimal. The sky, painted in pale azure with wisps of rose-tinged clouds, suggests a gentle breeze that disturbs neither the grain nor the olive branches. The interplay of light and shadow is subtle: roof tiles glow with a soft incandescence, while the stone wall casts only the faintest line of shade. This luminous equilibrium evokes a sense of suffused heat and stillness—an atmosphere Van Gogh described as “full of color and music.” In his Provence letters, he compared the region’s light to that of Japan, noting how vivid hues and clear air transformed even ordinary subjects into transcendent visions.

Brushwork and Textural Innovation

True to his Post-Impressionist style, Van Gogh’s brushwork here is both expressive and structural. He lays paint on thickly in some areas—such as the sunlit wheat—using impasto to create a tactile surface that catches light. In the sky and shadows, he employs looser, more fluid strokes, allowing underlayers of blue and white to peek through. Each blade of grass, each tile on the roof, is hinted at rather than meticulously detailed. The brushstrokes’ visible rhythm mirrors the natural vibrations of the scene—the rustle of wheat, the hum of cicadas, the sway of cypresses. In doing so, Van Gogh makes paint itself a living medium, capturing not only forms but the very pulse of the Provençal countryside.

Symbolism and Thematic Interpretation

While “Farmhouse in Provence” is ostensibly a landscape, Van Gogh imbues it with broader themes of stability, labor, and harmony. The sturdy farmhouse, with its weathered stones, stands as a testament to human resilience, having withstood seasons of drought and storm. The open gate suggests hospitality and the possibility of passage—between past and future, human society and the natural world. The surrounding fields, in the final ripeness before harvest, symbolize the cycle of birth, growth, and renewal. In letters, Van Gogh likened the act of painting fields and farmhouses to a spiritual practice, seeing in rural life a metaphor for humanity’s quest for sustenance and meaning.

Technical Analysis and Conservation Insights

Scientific examination reveals Van Gogh’s use of a limited but potent pigment range: chrome yellow for the fields and walls, viridian for cypress foliage, ultramarine and cobalt for the sky, and mauve lake accents in shadows. Infrared reflectography indicates minimal underdrawing—Van Gogh composed directly with brush and perhaps charcoal, reflecting his confidence and immediacy. Microscopy shows that the impasto regions have fine craquelure, typical of rapid drying in the Provençal climate. A recent conservation cleaning removed aged varnish, restoring the painting’s original vibrancy: the wheat gleams with newfound warmth, and the sky’s pastel hues regain their clarity.

Provenance and Exhibition History

“Farmhouse in Provence” remained with Theo van Gogh until Theo’s death in 1891. It then passed to Jo van Gogh-Bonger, who championed Vincent’s work throughout Europe. The painting first exhibited publicly at the 1892 Amsterdam show of Vincent’s works, later traveling to Parisian exhibitions in the early 1900s. By the mid-twentieth century, it had entered a major European museum collection where it features prominently in retrospectives on Van Gogh’s Arles period. Its consistent presence on exhibition calendars has solidified its reputation as a quintessential example of the artist’s Provence landscapes.

Critical Reception and Scholarly Perspectives

Early critical response to the farmhouse series was mixed; some praised the bold colors and emotional intensity, while others found the brushwork overly agitated. Mid-twentieth-century scholars reappraised the painting as a key milestone in Post-Impressionism, highlighting its formal innovations and psychological depth. Recent art-historical studies explore the farmhouse motif as part of Van Gogh’s broader exploration of “peasant” life and his engagement with rural subject matter in dialogue with contemporaries like Jean-François Millet. Eco-critical readings further examine the work as an early fusion of landscape and environmental awareness, in which human architecture and agricultural land coalesce into a unified ecosystem.

Influence and Modern Resonance

“Farmhouse in Provence” has inspired generations of artists fascinated by the interplay of color, light, and vernacular architecture. Expressionists looked to Van Gogh’s Arles works for their emotional directness, while contemporary plein-air painters emulate his dynamic brushwork and luminous palettes. In popular culture, the painting’s iconic imagery of sun-bathed stone and swaying wheat frequently appears on book covers, design merchandise, and digital media, symbolizing the rustic idyll. Its enduring appeal lies in its synthesis of formal mastery and heartfelt sincerity—a combination that continues to engage both viewers and practitioners of landscape art.

Conclusion: A Harmonious Ode to Rural Life

Vincent van Gogh’s “Farmhouse in Provence” stands as a testament to his profound connection with the Provençal landscape and its people. Through a radiant palette of yellows and greens, dynamic brushwork, and carefully calibrated composition, he elevates an everyday rural dwelling into an emblem of resilience and renewal. The painting’s balanced fusion of architecture and nature invites viewers to experience the agricultural rhythms and luminous air of southern France. More than a mere depiction of a house and field, “Farmhouse in Provence” expresses van Gogh’s enduring belief in art’s power to convey the dignity of simple lives and the quiet splendor of the natural world.