Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

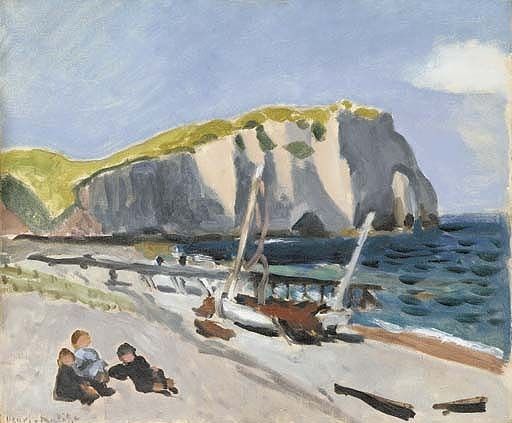

Henri Matisse’s “Falaises d’Aval” (1920) captures the famous chalk cliffs of Étretat with a disarming mix of simplicity and structural intelligence. A bright sky, a cool, textured sea, beached fishing boats, and a few small figures share the shore beneath the massive headland. At first glance the scene could be a casual note taken on a coastal walk. Look longer and the picture reveals a carefully tuned arrangement of diagonals and intervals, a measured palette in which warm sand and cool water meet along a ribbon of surf, and a brushwork that keeps the air moving while giving boats and cliff the weight they need. Rather than chasing spectacle, Matisse turns a storied view into a modern meditation on balance, rhythm, and the human scale of a working beach.

The Motif and Its History

Étretat’s cliffs were a magnet for nineteenth-century painters who emphasized theatrics—arched rock, crashing waves, weather at full voice. By 1920 Matisse was after something different. In the immediate postwar years he sought clarity and calm, favoring intimate interiors and local landscapes over heroic drama. “Falaises d’Aval” belongs to that pursuit. The cliff is present—and unmistakable—but it no longer dominates the picture like a monument. It becomes one mass among others, a pale counterweight to the blue sea and ocher beach, a backdrop that grounds the activities of boats and people. The shift in emphasis is crucial: Matisse doesn’t deny the site’s grandeur; he gently returns it to the scale of daily life.

Composition as a Map of Forces

The composition pivots on a clear diagonal. From the lower left the beach rises toward the middle distance where the cliff meets the water. The shore’s angle generates forward motion, guiding the eye from the resting figures in the foreground to the cluster of boats and then out toward the headland. This diagonal is steadied by lateral bands: the horizon and the near-parallel streaks of surf sit almost horizontally, calming the push of the beach. Vertical masts and spars puncture the sandy field at rhythmic intervals, confirming space without pedantry. A small driftwood beam or timber at the right foreground acts like a visual brace, keeping the painting from tilting entirely toward the sea. Everything interlocks: diagonals create energy, horizontals supply rest, verticals keep time. The result is a picture you can walk through at a comfortable pace.

Color and Tonal Climate

Matisse chooses a restrained, luminous palette that reads as coastal weather rather than coloristic display. The sea is a stack of blue-greens, from deep indigo patches to slate and turquoise, laid in short, lateral strokes that suggest a wind-freshened surface. The cliff is a chalky white tinged with warm gray, its grassy crown brushed with olive and citron. The beach is a field of ocher and pale rose with cool gray passages where damp sand darkens. The sky, a soft blue with milk-white cloud, spreads like a diffusing lens over everything. This measured harmony keeps the scene believable and breathable: cool on the left, warm on the right, fused by a narrow seam of foaming white at the water’s edge. Color here is climate—the temperature of a day—rather than ornament.

Brushwork and the Evidence of Looking

The picture’s life comes from the way paint is handled. Matisse’s strokes are brisk but intentional. On the water, he drags the brush laterally, letting stripes of color alternate to create the sensation of ripple and depth without detailing individual waves. The cliff’s faces are scumbled so that the canvas tone flickers through, evoking chalk’s powdery brightness. Boats are built from compact patches of dark and pale, their masts drawn in single, confident passes. The foreground figures are no more than a few rounded touches, yet their posture reads instantly—one reclines, another sits upright, a third leans into the conversation. The brush never labors to describe; it records relations the eye grasps first: angles, values, and directions.

Space Without Pedantry

Depth arises from value and scale, not from strict perspective diagrams. Larger, darker boats and figures occupy the foreground; mid-tones shape the middle beach; paler, smaller signs recede toward the cliff and horizon. The surf narrows as it runs up the beach, another gentle cue that distance is growing. The cliff’s top edge curves back just enough to imply volume without forcing three-dimensional illusion. This economy allows Matisse to preserve the flat, modern surface while giving viewers the sensation of breathable space. It’s a place you can enter without losing awareness that you’re looking at paint.

Boats and the Human Measure

Though no faces are individuated, the painting is full of human presence. Beached boats lie on their sides with masts angled like resting limbs. Nets, spars, and planks are suggested with a few strokes, indicating work paused rather than an empty show. In the left foreground, three figures sit on the sand, their dark silhouettes echoed by smaller groups farther downshore. These human notes give the cliff its true scale and shift the mood from sublime to inhabited. The view becomes a working shore where people talk, prepare boats, and watch the water. The significance of the headland is recalibrated: not a solitary spectacle, but the setting of a day.

Rhythm and Movement

“Falaises d’Aval” is quiet, but it never sits still. Your eye follows a loop: from the foreground figures across the pale arc of surf to the boats, up to the cliff’s bright face, then along the horizon to the sky and back down again through the slant of the beach. That circuit is powered by repeating rhythms—the alternating masts, the run of dark boat hulls, the picket of small figures against the sand. Even the cliff participates, its vertical striations echoing the boats’ spars. Rhythm replaces drama; movement becomes a matter of measured beats rather than narrative action.

Light and Weather

Light in this painting is maritime and even. There are no deep shadows or glinting highlights, just a pervasive clarity that keeps forms distinct and edges soft. The cliff’s white is not pure; it carries a hint of the sky’s coolness. The sea’s darker patches are not gloom; they’re the water’s changing face under a mild breeze. This is the kind of day fishermen prefer to prepare gear rather than to race storms—steady, breathable, and long-lighted. Matisse conveys the weather not by painting meteorological detail, but by tuning every color and value to the same calm key.

Comparisons and Dialogues

Set beside nineteenth-century treatments of Étretat, Matisse’s version looks deliberately modest. He avoids the dramatic arch that many artists centered, favoring a grounded stretch of cliff that reads as part of a larger coastline. Compared with his own Fauvist seascapes of 1905–06, the chroma here is restrained; yet the structural intelligence remains the same: large planes, strong diagonals, and decisive accents. The painting also converses with his Nice interiors of the same decade. The beach’s diagonal plays a role akin to a striped carpet; the masts are the verticals of chair legs; the cliff’s chalk plane works like a pale wall catching light from a window. Indoors or out, Matisse composes with the same grammar—few parts, tuned relations, and clarity over arena-sized drama.

Drawing and the Role of the Dark Line

A flexible dark line binds the scene. It strengthens the near boat’s gunwale, flicks up the masts, and underscores the surf’s edge in a few places where separation is needed. Yet the line never cages form. It thickens and thins, withdrawing in the sky and cliff faces so that color can carry the picture. This floating contour keeps shapes intelligible without hardening them; it’s a means of musical phrasing, not a fence.

Material Presence and the Beauty of Economy

One of the painting’s pleasures is how lightly it sits on the canvas. Paint is neither piled high nor thinned to stain. Where boats require weight, pigment grows denser; where sky and sand need air, strokes open and the ground peeks through. The economy extends to motif: a plank in the foreground is just that—a dark bar—and yet it helps hold the composition’s corner and implies the practical life of the beach. Every mark is doing at least two jobs: naming a thing and stabilizing the whole.

The Viewer’s Path Through the Picture

Matisse designs how we look, then gets out of the way. We enter at the lower left with the trio of figures, climb the diagonal of the beach to the clustered boats, and then arc to the cliff’s bright face. From there, the horizon’s gentle band releases us into the sky; we drop back by the sea’s darker patchwork and touch down again on the shore. With each circuit small discoveries accumulate: a pale green strip of grass topping the cliff, a soft gap that implies a notch in the rock, a flick of paint that becomes a rope or net. The picture rewards time not by revealing hidden narratives but by enriching the relational weave the longer you attend.

Symbolic Resonance Without Program

Matisse avoids allegory, yet the work carries resonance. Painted in a year when Europe was finding its equilibrium after war, the image of boats at rest near a permanent cliff reads as a quiet declaration of steadiness. The day is temperate, the sea navigable, the shore alive with ordinary activity. The painting doesn’t preach recovery; it embodies it. Through poise and measured motion, it proposes a world where work and landscape meet in calm cooperation.

Technique and the Logic of Simplification

The success of “Falaises d’Aval” rests on judicious simplification. Matisse identifies each element’s essential function in the composition—cliff as pale mass and backdrop; sea as lateral field of broken blues; beach as warm diagonal; boats as dark anchors and vertical notes; figures as scale and life—and paints only what is necessary to accomplish those roles. Details that don’t serve structure fall away. This logic gives the picture its clarity and longevity. The eye is not distracted; it is convinced.

Place, Memory, and the Felt Scene

Though anchored in a specific locale, the painting reads like a distilled memory of many beach days rather than a single topographical transcription. The cliff’s profile is recognizable, but its planes are generalized. The boats could belong to several mornings. The figures are types rather than portraits. This quality of remembered truth explains why the painting feels both exact and open: it holds the essential pattern of Étretat as experienced in real time—air, light, incline, work—without tethering itself to the constraints of reportage.

Why the Painting Endures

“Falaises d’Aval” endures because it makes a modern promise and keeps it. With few shapes and tuned color, it gives viewers a place to breathe. It offers a rhythm you can inhabit and return to—diagonal, horizontal, vertical; warm, cool, cool; figure, boat, cliff, sky. It never raises its voice, and yet it lodges in memory as firmly as the headland itself. In a world that often asks you to hurry past, Matisse crafts an image that rewards slowing down—the speed of a walk across a beach toward boats waiting at tide’s edge.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse’s treatment of the Étretat coast rejects spectacle in favor of clarity. In “Falaises d’Aval,” the chalk cliff, patterned sea, beached boats, and scattered figures join a measured chord where each part supports the others. Composition shepherds the gaze; color sets weather rather than display; brushwork records decisions instead of fussing details; space opens without theatrics. The result is a coastal scene whose quiet confidence feels inexhaustible. It is at once a view, a memory, and a lesson in how much resonance painting can achieve when it trusts essentials.