Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And Why This Canvas Matters

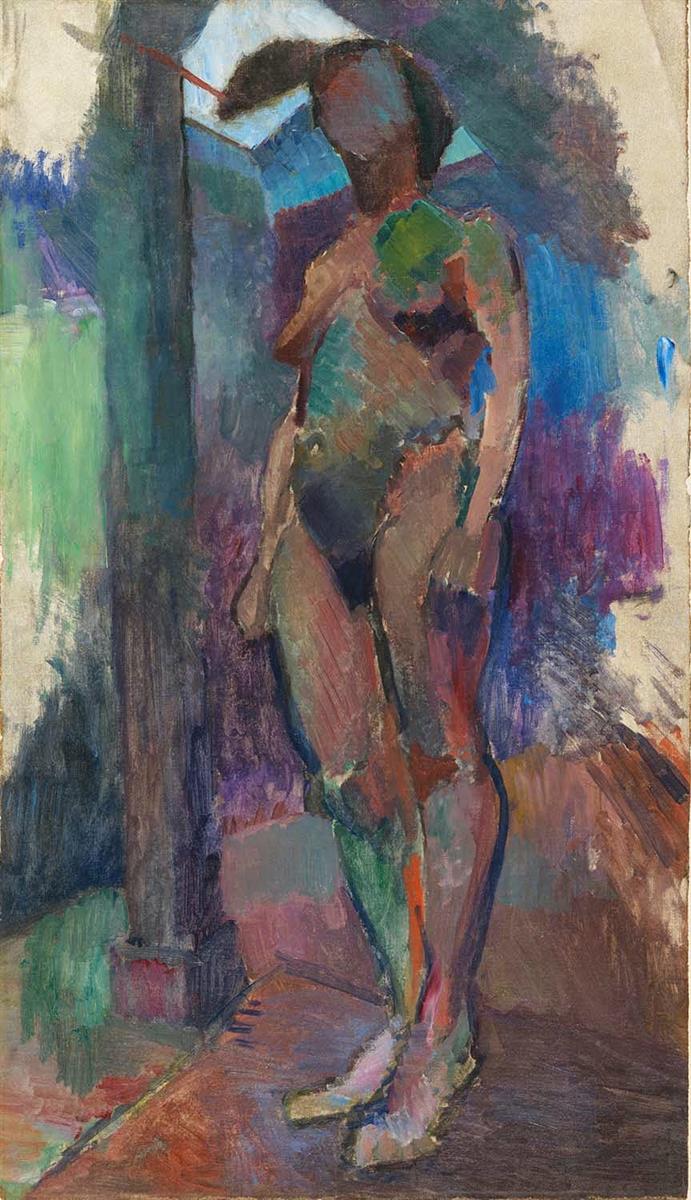

“Faith, the Model” was painted in 1901, at the exact moment Henri Matisse was testing how far he could push figure painting beyond academic finish and toward the structural use of color that would blossom into Fauvism. He had learned the rigors of life drawing, tonal modeling, and classical proportion at the École des Beaux-Arts. At the same time he was absorbing the lessons of Cézanne’s constructive planes, the expressive chroma of Van Gogh, and the decorative simplifications of the Nabis. This studio study of a standing nude records that pivot. The painting treats the model not as a polished classical ideal but as a living architecture assembled from boldly tuned color patches, abbreviated contours, and a shallow, ornamental space. It is a working laboratory where Matisse discovers that color can carry form, edge, and atmosphere all at once.

A First Reading Of The Scene

A nude figure stands in three-quarter view on a raised platform, weight settled on the back leg, the nearer foot angled slightly forward. Her head tilts and dissolves into a soft mask, hair swept up into a dark, winged shape. A vertical post to the left functions as both studio prop and compositional pillar. Around her, the room is translated into planes of green, violet, teal, and rose, with a diagonal belt of warmer browns and reds underfoot. The background is not a literal studio wall but a field of color weather, against which the body—built from patches of olive, coral, blue, and mulberry—advances and recedes. The overall sensation is of a figure emerging from atmosphere, the way a sculpture emerges from a block, only here the chisel is color.

Composition As A System Of Vertical And Diagonal Pressures

The design relies on a decisive interplay between verticals and diagonals. The post on the left and the long axis of the figure form the primary uprights, anchoring the canvas. The platform edges and the slanting floor establish diagonals that drive the eye inward from lower left to upper right. These forces meet at the torso, where the color concentration is densest. The head sits high and close to the picture’s top edge, an audacious placement that heightens the sense of immediacy. Negative spaces—particularly the cool wedge between post and figure and the luminous field to the right—are carefully shaped to keep the body legible without enclosing it in hard contour. The figure is both supported and challenged by the surrounding geometry, which is precisely the tension Matisse wants.

Color Architecture And The Early Grammar Of Fauvism

The painting’s construction is chromatic rather than linear. Flesh is not represented by a single “skin tone” but by a chord: warm ochres and siennas collide with teal greens, slate blues, and flashes of cadmium-like orange. These complements are not decorative flourishes; they are structural notes that carve volume and create temperature transitions across planes of the body. The left calf, for instance, is cooled by green against the heat of the thigh; the abdomen is laid in with lavender and olive that turn toward warmth at the flank; the shoulder gathers a bright green that pushes forward against the violet environment. Black is used sparingly as a live color—concentrated in the hair mass and in a few crucial contours—never as a dead outline. Every hue exists to keep its neighbor alive, a principle that will define Matisse’s Fauvist practice within a few years.

Drawing Through Abutment Rather Than Outline

If you search for academic contour, you find only fragments: a dark seam along the back of the leg, a quick hook at the wrist, a brief edge defining the knee. More often Matisse draws by abutment—letting one color press against another to create an edge. The outer line of the torso is authored by the collision of cool violet background and warm olive flesh; the inner edges of thigh and abdomen appear where complementary patches meet. This method preserves the unity of the painted surface, allowing the figure to feel embedded in the same air as everything around it. It also grants the artist extraordinary economy: with a handful of tuned patches he can suggest curvature, weight, and turning without resorting to tight drawing.

Brushwork, Tempo, And The Record Of Looking

The surface registers a deliberate variety of touch. On the background walls, Matisse lays long, planar strokes—scumbled, transparent in places—so that earlier layers breathe through, creating a vibrating air. In the figure, strokes become shorter, shaped to the anatomy they describe: a vertical pull to build the shin, a diagonal drag to turn the hip, a stippled cluster to round the shoulder. Paint thickens at the fulcrum points—the clavicle, the front of the thigh, the ankle—catching real light and intensifying the optical light of color. The handling remains candid. You can feel the painter stepping back, testing balances, and returning to lay one decisive patch that suddenly makes the posture cohere.

Light, Atmosphere, And The Choice To Model With Temperature

Rather than cast a single spotlight, Matisse evokes an enveloping, studio light that softens shadows into zones of temperature. Cool notes hollow the under-planes of limbs; warm surges swell the fronts that face the imagined source. The model does not carry a theatrical highlight; she glows by relationship—cool against warm, dull against saturated. This approach keeps the body matte and sculptural, closer to carved stone than glossy skin, and it allows color harmony to govern the whole scene without being overruled by a fixed sunbeam.

Space Compressed Into A Decorative Field

The architecture of the room is simplified into shallow planes. The upright post pushes forward like a screen, the floor tilts up, and the far wall flattens into bands of violet, teal, and gray. Depth cues exist—platform edge, diagonal floorboards—but recession is intentionally restrained so that the figure stands within an ornamental fabric rather than a deep box. This compression is not a failure of drawing; it is the modern choice that lets color and shape maintain sovereignty. The surface reads as a designed pattern, and the model is a central motif within that pattern.

The Pose, Weight, And The Ethics Of Presence

The model’s contrapposto—one knee soft, the other leg bearing weight—creates a natural S-curve that Matisse amplifies through color. The forward tilt of the head, rendered with minimal facial detail, rejects anecdote and emphasizes bodily presence. Hands are simplified into blocks; feet, though carefully placed, are broadly stated. The effect is dignified and unsentimental. The nude is not a seductive spectacle but a subject of study and respect. By refusing to individualize the face, Matisse directs attention to the living structure of the body—the weight distribution, the tensions of muscle and skin, the equilibrium of a held pose.

The Studio Made Abstract

We recognize the artifacts of the life room—platform, prop post, corner of a wall—but they have been overtaken by the logic of color fields. The left side dissolves into a cool green flare, while the right blooms in ultramarine and violet, rising behind the figure like a curtain. These zones do not describe plaster or fabric; they perform as counterweights to the warm passages of flesh. In this sense the “studio” is less a place than a set of oppositions engineered to make the figure resonate. The abstraction of setting clears anecdotal noise and installs the model as the picture’s harmonic center.

Relation To Cézanne, Gauguin, And Van Gogh

The painting converses with three crucial elders. From Cézanne it inherits the principle of building form through adjacent color planes rather than contour and shading; from Gauguin, the willingness to simplify silhouettes and use non-local color for expressive truth; from Van Gogh, the belief that directional brush can carry emotion and energy without sacrificing coherence. Yet the temperament is unmistakably Matisse’s—more balanced than Van Gogh, less hieratic than Gauguin, less tectonic than Cézanne. The aim is equilibrium, a decorative whole where every element has its appointed role.

Materiality, Pigments, And The Skin Of Paint

Industrial pigments available by 1901—cobalt and ultramarine blues, viridian and emerald greens, earthy ochres, and cadmium-family warms—permit the high-contrast harmonies on the body without turning muddy. Matisse sets lean, translucent layers in the background against richer, paste-like applications on the figure, so that flesh appears materially denser than air. Occasional areas of thinly covered ground—especially along the right edge—permit actual canvas light to mingle with painted light, keeping the surface fresh and breathable. The painting never hides its facture; the material truth of oil on fabric is part of its meaning.

Rhythm And The Viewer’s Path Through The Picture

The composition coaches a specific route for the eye. Many viewers enter along the low left diagonal, ascend the cooler edge of the shin, dwell at the warm–cool hinge of the knee, rise through the abdomen’s olive-lavender chord to the chest, and finally rest at the dark head against the pale left corner. From there the eye drifts into the violet field, slides down the right edge of the body, and returns to the feet. That loop repeats, each circuit revealing new correspondences—a blue echo in the floor that answers a note in the calf, a green in the shoulder that balances a patch low on the shin. The painting is choreographed looking.

Abbreviation And The Courage To Omit

Matisse knows what to leave out. Fingers, features, floorboards, prop details, and the platform’s construction are abbreviated to the point of emblem. This is not carelessness but clarity. Omission allocates attention to the essential relations—color intervals, weight shifts, edge behavior—that make the figure stand and breathe. It also invites the viewer’s imagination to complete the scene, a collaboration that keeps the picture alive long after description would have exhausted it.

The Decorative Ideal Emerging From Observation

Even at this early date, Matisse’s famous ideal—an art of balance and serenity—is visible in embryo. Every zone of the canvas takes up a role in a stable chord. The cool pillar and teal wedge hold one side; the violet field cools and deepens the other; warm and cool interlock within the body to prevent dominance by either. The result is calm without stagnation, energy without noise. Observation provides the motif; decorative order provides the meaning.

Why “Faith, the Model” Endures

The painting endures because it shows a young master solving several modern problems at once. It proves that color can replace laborious shading as the engine of form, that a figure can command a room without narrative, and that the surface of a painting can be both decorative and truthful. It honors the model’s presence with dignity while refusing spectacle, and it forges a vocabulary—patch against patch, warm against cool, plane against plane—that will support Matisse’s breakthroughs for the rest of his career. Seen today, the canvas retains the thrill of invention: you can watch a modern language being born.

How To Look Slowly And Profitably

Stand back and register the big structure: vertical pillar, vertical figure, diagonal floor, wide bands of violet and teal. Then move closer and trace how edges arise from adjacency, not from line. Notice the temperature flips across each limb, the way cool greens scoop under warm ochres to turn a calf or shoulder. Observe how thicker passages collect at anatomical hinges, catching light like skin under tension. Finally, step back again until the parts lock into a single accord. In repeating that near-far rhythm, you re-enact the painter’s own process of testing and tuning the whole.

Legacy Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Faith, the Model” stands as a crucial rehearsal for the famous Fauvist figures and odalisques to come. The chromatic courage, the confidence in omission, the shallow, patterned space, and the ethical steadiness of the gaze are all here in seed. Over the next few years Matisse will heighten chroma, simplify contour into sweeping arabesque, and flood interiors with saturated fields. But the grammar that makes those audacities legible—color as structure, adjacency as edge, balance as aim—is proven in this studio session with a single model and a handful of tuned pigments.