Image source: artvee.com

Overview of the Poster

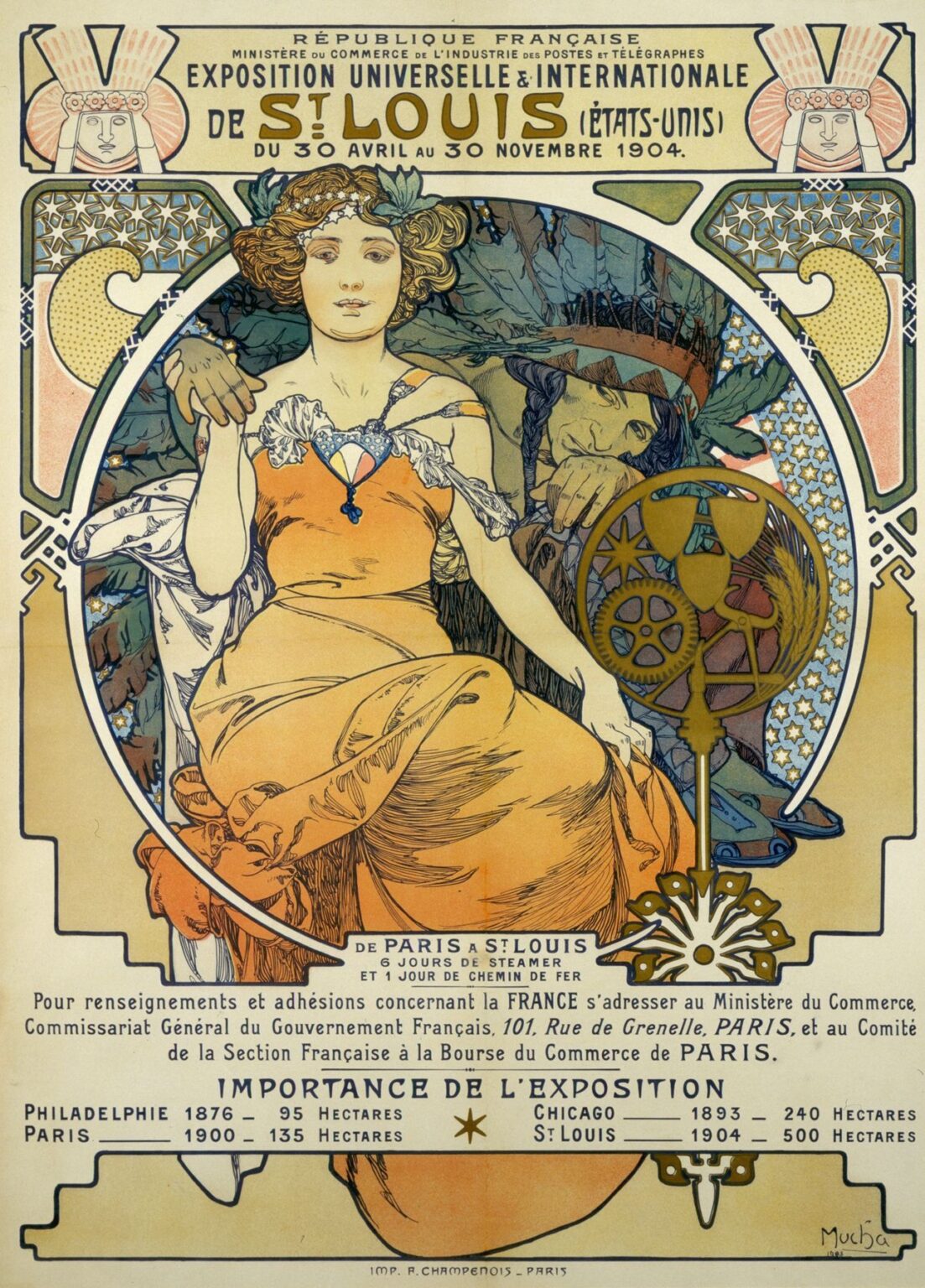

“Exposition Universelle & Internationale de St. Louis (États‑Unis) du 30 Avril au 30 Novembre” is a monumental 1903 color lithograph by Alphonse Mucha, commissioned by the French government to promote the Parisian participation in the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis. At its center sits an allegorical female figure, draped in classical robes and crowned with a wreath, her posture relaxed yet dignified. Behind her, a Native American chief in feathered headdress leans forward, embodying the hosts of the fair. To the right, an ornate medallion of cogs, wheat, and compasses symbolizes industry, agriculture, and exploration. The poster’s intricate frame of star patterns and stylized curvilinear motifs, combined with custom typography, transforms a utilitarian announcement into a lavish celebration of cultural exchange and technological progress.

Historical and Cultural Context

In the early twentieth century, World’s Fairs represented the pinnacle of national prestige, technological innovation, and cultural display. The 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis marked the centennial of the 1803 land acquisition and showcased new inventions, art, and ethnographic exhibits from around the globe. France, keen to assert its cultural leadership, sent a significant pavilion featuring fine arts, crafts, and colonial displays. Posters by leading artists like Mucha were integral to this effort, plastering Parisian streets to drum up interest and patriotic support. The Belle Époque’s spirit of optimism and fascination with speed, electricity, and exoticism finds expression in this poster, which merges classical allegory with contemporary industrial motifs.

Alphonse Mucha’s Artistic Trajectory in 1903

By 1903, Mucha had become the foremost poster artist of the Art Nouveau movement. After his breakthrough “Gismonda” poster for Sarah Bernhardt in 1895, he produced celebrated works for cosmetics, perfume houses, and cultural events. His signature style—graceful female forms, sinuous lines, and ornate frames—had crystallized by the turn of the century. Parallel to his commercial success, Mucha embarked on his lifelong project “The Slav Epic,” which explored Slavic history in monumental canvases. The St. Louis Exposition poster sits at this creative apex, synthesizing Mucha’s decorative prowess and his capacity to convey narrative and symbolism. It reflects his mastery of multi‑stone lithography and his conviction that commercial art could attain the dignity of fine art.

Commission and Purpose of the Exposition Poster

The French Ministry of Commerce, Industry, Postes et Télégraphes commissioned Mucha to design a poster that would broadcast the dates, venue, and significance of the St. Louis Exposition. The government sought both to inform potential exhibitors and to galvanize public interest in France’s contributions. Mucha was tasked with balancing factual content—exposition dates, locations, and logistical notes—with evocative imagery that would stir civic pride. By integrating allegorical figures, ethnographic reference, and symbols of progress, Mucha’s design transcended its promotional function. It became an emblem of national identity, linking France’s classical heritage with its modern industrial achievements, and positioning the exposition as a bridge between past and future.

Composition and Spatial Organization

Mucha’s layout is meticulously orchestrated. A broad horizontal header announces “République Française” and exposition details in bold, custom lettering, forming a visual crown. Below, a large circular frame encloses the two central figures, whose heads nearly touch the top edge of the circle, creating an intimate focal point. The allegorical woman occupies the left foreground, her body angled toward the viewer, while the Native American chief reclines behind her, his gaze directed downward. To the right, the gear‑and‑wheat medallion overlaps the circle’s edge, bridging pictorial and textual zones. Flanking the central circle, panels of geometric and star‑patterned ornament extend to the poster’s margins, effectively containing the scene. A lower typographic block, listing travel times and comparative exposition sizes, provides balance and structure.

Color Palette and Lithographic Technique

Mucha’s palette for the St. Louis poster is both harmonious and symbolic. Earthy greens and ochres evoke agriculture and nature, while muted blues and grays suggest commerce and global connection. Warm peach tones enliven the allegorical figure’s skin, contrasting with the subdued earth tones of her robe. The Native American’s headdress incorporates richer hues—deep reds and teal—to signify cultural distinction. Rich metallic-like gold in the industrial medallion highlights the promise of progress. Each color was applied via a separate lithographic stone, requiring precise registration. Mucha exploited the translucency of certain inks to achieve subtle tonal gradations in drapery and background panels. The technical sophistication lends the poster a luminous quality that remains vivid over a century later.

The Allegorical Figure and Secondary Icon

At the composition’s heart is the allegorical female figure, representing France or perhaps the spirit of civilization. Her classical drapery, reminiscent of ancient temple sculptures, underscores continuity with Western cultural heritage. She holds a slender baton or staff, its tip resting on the industrial medallion, suggesting guidance and leadership. Behind her stands the Native American chief, whose formal attire and headdress reference the host nation’s indigenous peoples—albeit through the lens of European Romanticism. His presence conveys hospitality and the exotic allure of the New World. The juxtaposition of these two figures embodies mutual recognition: Europe’s artistic tradition meeting America’s frontier promise.

Symbolism and Iconography

Much of the poster’s power lies in its layered symbolism. The circular frame evokes unity and the globe, signifying the exposition’s international scope. The industrial medallion—a composite of gears, wheat sheaves, and navigational compasses—symbolizes the fair’s three pillars: industry, agriculture, and exploration. The wheat speaks to sustenance and France’s role as a breadbasket, the gears to mechanical innovation, and the compass to global trade. The Native American headdress, while stylized, alludes to St. Louis’s historical roots in the Louisiana Purchase and indigenous presence. The allegorical figure’s laurel wreath and serene gaze crown France’s cultural contributions, asserting artistic leadership amid technological change.

Decorative Motifs and Ornamental Frame

Mucha’s hallmark ornamentation appears in the intricate borders that enclose the central scene. Stylized star patterns recall the American flag, echoing the exposition’s U.S. setting, while delicate vine scrolls reference France’s Art Nouveau vegetative idiom. The header and footer panels feature simplified geometric forms that balance curvilinear flourishes. Mucha often spoke of “total decoration,” and here every inch—positive or negative space—is treated as an opportunity for artistry. Even the typographic zone below is framed by decorative lines and floriated motifs, unifying information with visual splendor. This holistic approach transforms the poster into a decorative object, worthy of display beyond its fleeting promotional purpose.

Integration of Typography and Imagery

Mucha’s integration of text and image elevates both elements. The custom lettering of the header—capital letters with stamped serifs and ribbon‑like crossbars—mirrors the linear quality of the ornamental vines. Exposition dates and logistical notes appear in a more restrained serif, ensuring legibility without clashing with the decorative scheme. The poster’s bottom section lists comparative exposition sizes—Philadelphia (1876), Chicago (1893), Paris (1900), and St. Louis (1904)—in a clear linear progression, emphasizing France’s ongoing engagement with world fairs. The text is anchored by slender horizontal lines adorned with star motifs, connecting content to context. Typography thus becomes part of the image, reinforcing meaning through form.

Line, Form, and Visual Rhythm

Line is the structural backbone of Mucha’s design. He varies line weight to convey depth and emphasis: bold outlines define primary figures, while finer filigree lines model facial features, drapery folds, and background ornament. The curving contours of the allegorical figure’s drapery flow into the vine scrolls, creating a seamless transition between figure and frame. The circular motif at the center contrasts with the orthogonal header and footer, introducing dynamic tension that guides the eye in a circular motion. Diagonal thrusts—such as the woman’s staff and the chief’s outstretched arm—add directional cues that lead viewers from pictorial to textual zones and back. This interplay of curves, angles, and lines imbues the poster with energetic harmony.

Light, Shadow, and Texture

Although primarily a flat medium, lithography can suggest volume through tonal variation and texture. Mucha employs delicate shading in the figures’ garments and skin, using fine hatching and translucent ink layers to imply three‑dimensional form. The industrial medallion’s metallic sheen is achieved through thicker ink application and stylized highlights. Background panels maintain more uniform tones, creating visual respite and ensuring foreground figures stand out. The poster’s textured appearance—visible in mottled panels and stippled star fields—conjures the tactile qualities of stone, metal, and fabric. These textural contrasts heighten sensory engagement, inviting viewers to appreciate both technical skill and thematic richness.

Emotional Resonance and Public Reception

Upon its release, the poster captured the public imagination by fusing patriotic pride with the promise of international cooperation. Parisians encountering the design on street corners would have felt both nostalgia for classical heritage and excitement for modern marvels awaiting them in St. Louis. The allegorical figure’s serene composure conveyed confidence, while the chief’s contemplative presence hinted at cultural exchange. The industrial medallion suggested practical benefits—new markets, technological partnerships, agricultural knowledge. Mucha’s ability to evoke complex emotions—pride, curiosity, anticipation—within a single image demonstrates his genius for public persuasion and aesthetic appeal.

Influence on Art Nouveau and Poster Art

“Exposition Universelle & Internationale de St. Louis” stands among Mucha’s most accomplished posters, representing the apogee of Art Nouveau commercial art. Its seamless fusion of decoration, narrative, and typography influenced generations of designers across Europe and America. Schools of graphic art adopted Mucha’s principles—holistic composition, custom lettering, and organic ornament—for applications ranging from magazine illustration to corporate branding. The poster’s success helped solidify the role of color lithography in mass communication and validated advertising as a legitimate art form. Even today, echoes of Mucha’s style can be found in contemporary design, where the interplay of beauty and information remains paramount.

Conservation and Legacy

Original lithographs of the St. Louis Exposition poster are prized by collectors and exhibited in museums specializing in graphic arts. The fragile papers and early color inks require careful preservation—controlled light exposure, humidity regulation, and archival framing. Modern reproductions and digital archives have democratized access, allowing scholars and enthusiasts to study Mucha’s technical innovations. Retrospectives of Belle Époque art frequently feature this poster as a case study in the commercialization of avant‑garde aesthetics. Its influence endures in design curricula, where it exemplifies the potential of illustration to shape cultural narratives and historical memory.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s “Exposition Universelle & Internationale de St. Louis (États‑Unis) du 30 Avril au 30 Novembre” transcends its promotional mandate to become a lasting work of art. Through masterful composition, refined palette, and intricate ornament, Mucha weaves together allegory, ethnography, and industrial symbolism into a unified whole. The poster celebrates both France’s classical heritage and the modern spirit of technological progress and international exchange. Its enduring appeal lies in the seamless integration of form and function, where decorative beauty amplifies informational content. Over a century later, this lithograph continues to enchant audiences and inspire designers, embodying the timeless promise of cultural dialogue and artistic innovation.