Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

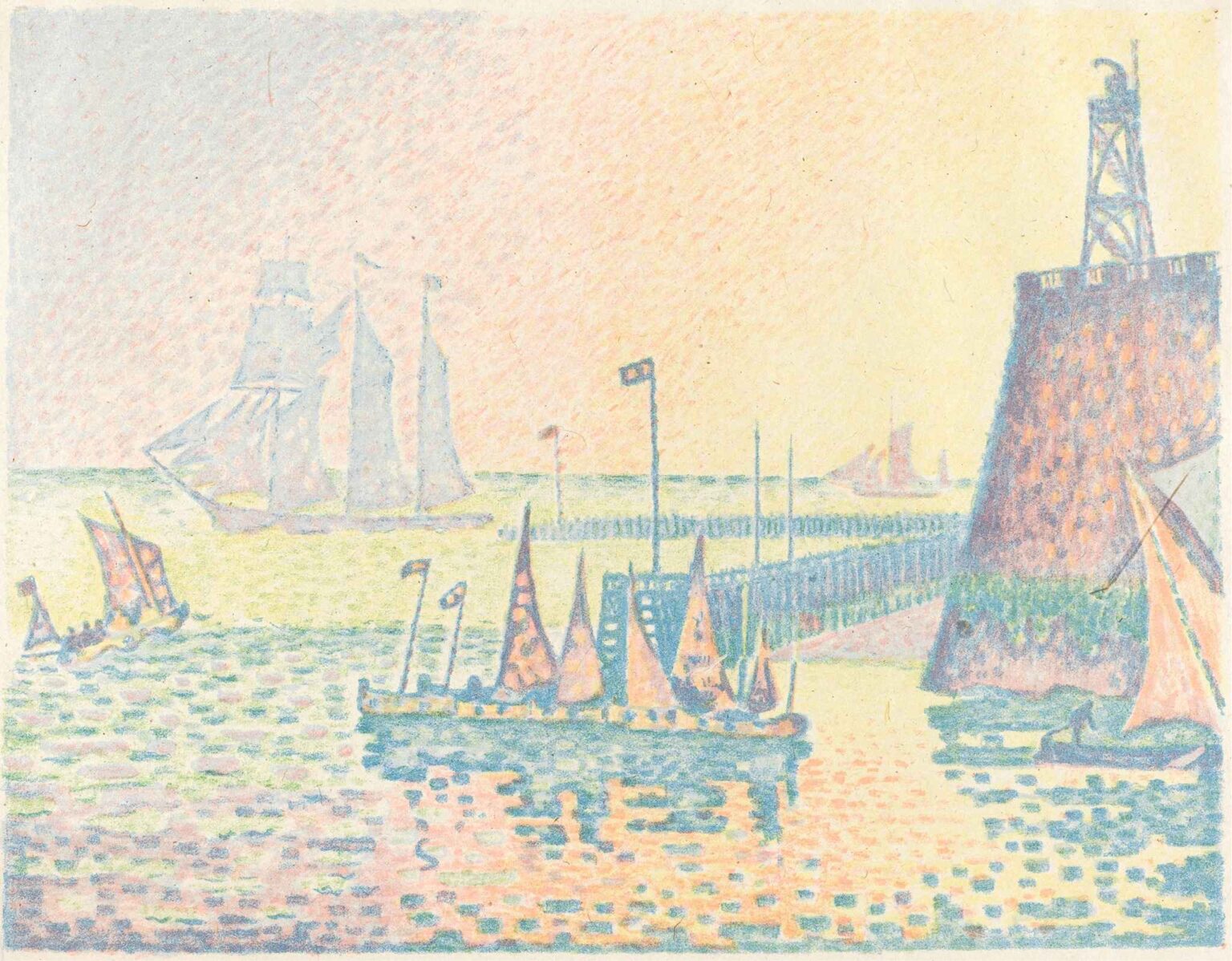

Paul Signac’s Evening (1898) is a radiant example of Neo-Impressionist painting and a profound meditation on the interplay of light, color, and atmosphere. Created during a period when Signac was refining the technique of pointillism—first developed with Georges Seurat—Evening is both an aesthetic experiment and a poetic vision. Through its softly glowing hues and gently lapping sea, the painting offers a tranquil yet meticulously structured view of a harbor at dusk.

This analysis will explore the historical context of the painting, Signac’s approach to color and composition, the scientific underpinnings of Neo-Impressionism, the emotional and symbolic content of the work, and its lasting influence on modern art.

The Artist: Paul Signac and the Neo-Impressionist Movement

Paul Signac (1863–1935) was a pivotal figure in the development of post-Impressionist painting in France. After meeting Georges Seurat in the early 1880s, Signac became a devoted practitioner of pointillism—or more accurately, divisionism—a method based on applying small, distinct dots or strokes of pure color that visually blend at a distance.

Unlike the spontaneous brushwork of the Impressionists, Neo-Impressionism emphasized order, structure, and color theory. Signac and Seurat drew on contemporary scientific studies in optics, particularly the work of Michel Eugène Chevreul and Ogden Rood, to inform their approach to chromatic harmony.

By 1898, the year Evening was painted, Signac had become a mature artist deeply invested in marine landscapes. His travels along the French coast inspired numerous views of harbors, sailboats, and seascapes—each rendered in luminous mosaics of color that elevated the ordinary into the poetic.

Composition and Layout

The composition of Evening is structured with remarkable clarity. The right side of the canvas is anchored by a prominent harbor wall or jetty, built from reddish stones that glow warmly in the sunset light. A watchtower-like structure stands atop the jetty, silhouetted against the golden sky. The left and central portions of the canvas are filled with a calm expanse of water, dotted with sailboats, some near, some ghostlike in the distance.

What immediately captures attention is the rhythmic arrangement of vertical and diagonal lines. The masts of the boats and the pilings of the dock are mirrored in the rippling reflections on the water. The boats themselves are arranged in a staggered formation, guiding the eye deeper into the pictorial space. A tall-masted ship sails in from the background, bringing a sense of gentle motion to the serene atmosphere.

The entire scene seems suffused with the golden and lavender tones of sunset, giving the work its titular essence: a moment suspended between day and night, activity and stillness.

Pointillism and Optical Harmony

Signac’s technique in Evening demonstrates the precision and vision of Neo-Impressionist methods. The painting is composed of countless individual dabs of color—orange, lavender, green, blue, and yellow—placed adjacent rather than blended on the palette. This method, known as divisionism, relies on the viewer’s eye to do the mixing.

Instead of creating forms through modeling and shading, Signac builds the image through color contrasts. Shadows are not gray, but composed of complementary tones. The sky transitions not through gradient washes but through pointillist textures of peach, blue, and rose. The water is rendered as a shimmering patchwork, reflecting not just the physical surroundings but the emotional temperature of the scene.

Signac believed that color could be liberating, expressive, and even moral. In contrast to academic painting’s earthy palettes, his bright, pure hues symbolized a vision of harmony and freedom. In Evening, this ideal is fully realized.

The Mood of Evening

Despite its systematic technique, the emotional resonance of Evening is unmistakable. The palette is suffused with soft pastels, giving the painting a dreamy, meditative tone. The quiet of dusk is palpable—not a single figure populates the canvas, yet human presence is felt through the moored boats and built structures.

The title alone invites contemplation. “Evening” suggests closure, reflection, and rest. It evokes the end of labor, the return to port, the final warmth of the sun before nightfall. Signac captures not just a time of day but a state of mind—a calm, almost spiritual stillness that soothes and balances the senses.

The painting can be seen as a counterpoint to the chaos of industrial modernity. Rather than bustle or conflict, Evening offers a vision of serenity made possible through the union of man and nature, structure and spontaneity.

Symbolism and Interpretation

Although Signac was not a Symbolist in the strict sense, his work often carries layered meanings. In Evening, the harbor can be interpreted as a space of safety and return, while the open sea beyond may symbolize the unknown or future journeys. The lighthouse or tower suggests vigilance, protection, and perhaps isolation.

The glowing sky, with its veil of dots, may also serve as a metaphor for the transitory nature of life. Evening is, after all, a threshold—neither day nor night, but a fleeting in-between moment. Signac’s rendering invites reflection on such liminal spaces, where time feels slowed and consciousness deepens.

His lifelong anarchist beliefs and advocacy for individual freedom may also inform the painting. By choosing scenes of maritime openness and structuring them with color rather than line, Signac implies a world where order emerges naturally from liberty—a theme consistent with his ideological values.

Color Theory in Action

One of the most remarkable aspects of Evening is its demonstration of advanced color theory. Signac adheres to the principles of simultaneous contrast, wherein complementary colors placed side by side intensify one another. The interplay between orange and blue, pink and green, gives the scene a visual vibration that mimics the effects of light itself.

This chromatic interaction is most evident in the reflections on the water. Rather than rendering the sea as a flat expanse of blue, Signac dots it with countless flecks of coral, lilac, mint, and gold. These hues not only create a sense of light on water but evoke the movement of waves and breeze.

The sky, too, avoids monotony by incorporating pinks and purples into its yellows and creams. This subtle gradation of hue is not arbitrary but scientifically calculated to stimulate visual harmony. The result is a landscape that pulses with inner light, despite the absence of direct sun.

Influence and Legacy

Evening exemplifies the legacy of Neo-Impressionism and its impact on modern art. Signac’s innovations in color and structure would influence artists such as Henri Matisse, who adopted divisionist techniques early in his career. The Fauves, with their bold color palettes, owed much to the experiments of Signac and his circle.

Moreover, the painting demonstrates how scientific principles could coexist with aesthetic pleasure. While rooted in theory, Evening is never cold or mechanical. It speaks to the senses as much as to the intellect. This fusion of rigor and lyricism became a hallmark of early modernism, informing not only painting but also design, architecture, and graphic arts.

In contemporary terms, Signac’s work offers lessons in balance: between analysis and emotion, structure and freedom, individuality and harmony. Evening continues to be admired for its subtle power and enduring beauty.

Contrast with Seurat

Although Signac was heavily influenced by Georges Seurat, their approaches diverged over time. Seurat’s paintings, such as A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, are more static and cerebral, often resembling visual equations. Signac, by contrast, embraced more fluid subjects and infused his work with warmth and vitality.

In Evening, Signac achieves a lyrical expressiveness that surpasses mere technique. Where Seurat’s compositions are often symmetrical and austere, Signac’s are looser, more organic. He maintained the discipline of pointillism but applied it to scenes of beauty, leisure, and joy rather than moral tableaux.

This evolution helped Neo-Impressionism remain relevant into the 20th century, paving the way for modernist movements that sought to reconcile personal vision with formal innovation.

The Role of Nature and the Sea

For Signac, the sea was more than a subject—it was a metaphor. As a lifelong sailor, he found in water a symbol of freedom, movement, and change. In Evening, the calm harbor and open horizon together create a dialogue between containment and possibility.

The sea also allowed Signac to explore the relationship between light and surface. Water is a natural mirror, and in this painting it reflects not only sky and sail but also the shifting moods of dusk. The motion of the water, though not overtly turbulent, gives the painting a living quality that changes with each viewing.

The interplay between human presence (boats, docks, architecture) and the enduring rhythms of nature (tide, wind, sunlight) underscores the delicate balance Signac sought to capture. In this harmony lies the painting’s emotional center.

Conclusion

Paul Signac’s Evening (1898) is a masterwork of Neo-Impressionism, synthesizing scientific precision with poetic vision. Through its carefully constructed color fields, luminous atmosphere, and evocative subject matter, the painting elevates a simple harbor scene into a meditation on time, beauty, and the human spirit.

It exemplifies the ideals of a movement that sought clarity without rigidity, and emotional depth without sentimentality. More than a display of technique, Evening is a visual hymn to peace—a gentle invitation to pause, observe, and appreciate the quiet splendor of the world at dusk.

In an age increasingly defined by speed and spectacle, Signac’s serene harbor remains a powerful reminder of the value of slowness, balance, and radiant simplicity.