Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: A Grove That Breathes

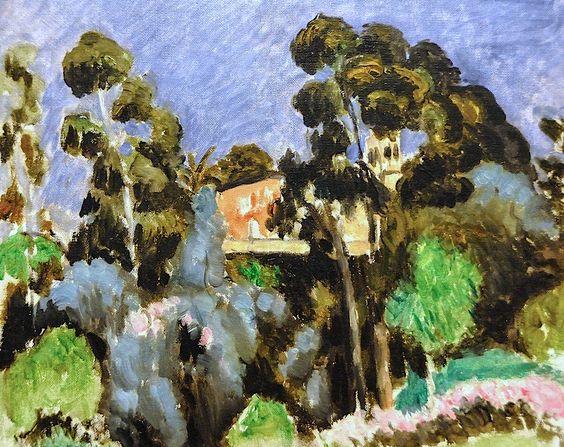

“Eucalyptus, Mont Alban” presents a sunlit hillside thick with eucalyptus and garden growth, a pink-ochre villa half veiled behind trunks, and a bowl of Mediterranean sky. The canvas is compact yet expansive: tree masses surge upward; foliage gathers in buoyant clumps; strokes of blue, green, and earthen black knit the scene into a living fabric. With a few large relations—dark verticals, light architecture, cool sky—Matisse builds a landscape that reads in a heartbeat and deepens the longer you look.

1918 and the Turn to the South

Painted in 1918, the work belongs to the first season of Matisse’s Nice period. After the austerity of the mid-1910s, he found in the Côte d’Azur a steadier light and a calmer, more decorative grammar: tuned color rather than blazing saturation, shallow space that stays close to the picture plane, and black used as an active, positive pigment. This landscape shows those priorities in the wild—no theatrical sky, no heroic mountain vista, but a cultivated slope where house and trees converse in balanced tones.

The Site and the Idea of Mont Alban

Mont Alban overlooks Nice; its slopes mix villa gardens with Mediterranean species—pines, olives, eucalyptus. Matisse is less concerned with naming each tree than with catching the climate they weave together. He gives us the eucalyptus as billowing, scalloped crowns perched on swift, dark trunks; he lets undergrowth flash in lighter greens; he slots the villa between trunks like a warm chord within orchestral strings. Place becomes climate before it becomes topography.

Composition: Vertical Rhythms, Horizontal Rest

The design is a play of uprights against a banded backdrop. Tree shafts rise like calligraphic strokes; rounded canopies interlock, creating a syncopated skyline; the villa sits as a warm rectangle midway up the picture; the sky is a single, stable field. This counterpoint of vertical pulse and horizontal rest is classic Matisse. The eye climbs through the trees, rests on the house, then lifts to the sky’s cool breadth before dropping back into foliage. Large forms carry the scene; detail is kept on a short leash.

Palette and the Mediterranean Light

Color is tuned, not loud. The sky is a chalky ultramarine brushed in diagonal sweeps; olives and eucalyptus gather in greens that lean from viridian to sage to near-black; undergrowth flares in mint and emerald; the villa warms with apricot and ochre. A few notes of pink mark flowering shrubs, cooling quickly where they dive under green. Because saturation is moderated, temperature does the expressive work. Warm house against cool sky; cool foliage around warm soil; black and near-black cutting through to supply structure. The effect is of steady daylight rather than a dramatic hour.

Black as a Positive Color

Matisse’s darks are not outlines but pigments. He uses near-black to state trunks, to articulate the undersides of canopies, and to carve the negative spaces that set the villa free. Where those blacks meet blue sky, they gleam; where they cut into green, they intensify it; where they skirt the house, they make its warmth ring. The painting’s bass line is this lattice of darks, the framework that keeps the airy palette from drifting.

Eucalyptus as Motif and Movement

Eucalyptus crowns here are scalloped, almost cloudlike, each formed by clustered, comma-like strokes that catch and release light. Their repeated convex edges establish a rolling rhythm across the top half of the canvas, while the trunks—slim, assertive, slightly curved—give a felt sway. Matisse doesn’t catalogue leaves; he choreographs masses. The result is not botanical illustration but the sensation of trees moving as a group in afternoon air.

Brushwork: The Pace of Making

The surface keeps the time of its making. Sky strokes run obliquely, faint ridges catching highlights. The tree crowns are built with packed, rounded touches that overlap like scales. Trunks are laid in stronger, viscous passes of near-black that widen and thin with the pressure of the brush, recording gesture without theatrics. The villa walls are broader, flatter sweeps, nudged warmer or cooler to seat them in light. Everywhere Matisse resists cosmetic blending; zones end visibly against one another so the painting remains lively while communicating calm.

Edges, Joins, and Intervals

Edges are tailored to the job. Where trunk meets sky, the seam is crisp; where leaf mass meets air, strokes feather, letting violet-gray pockets of sky breathe through. The villa’s roofline is firmer, a necessary edge in a garden of soft transitions. Equally important are the intervals: slim slices of light where trunks separate, a pale path of blue glinting between crowns, the gap that reveals the warm façade. Those pockets of air keep the dark scaffold from clumping and let the composition breathe.

Space Held Close to the Plane

Depth is achieved through overlap and value shift, not through vanishing points. Foreground foliage is darker and more saturated; the villa and far canopies lighten and cool; the sky is the farthest, flattest plane. Yet the space never collapses to wallpaper, because the dark trunks step forward like pillars and the house registers as a solid mass tucked behind them. Matisse keeps us near the surface while giving enough depth to feel the hillside.

Climate Rather Than Weather

The painting avoids meteorology—no sunburst, no storm. Light is a set of tuned relationships that could stand for many days: sky present but not blazing, shadows inferred rather than cast, color registering temperature more than hour. This refusal of spectacle aligns with Matisse’s postwar ethos: serenity by structure, not by effect.

The Villa: Warm Chord in a Green Orchestra

The house is a small, crucial chord. Its apricot façade and creamy parapet are the painting’s warmest notes. They prevent the green masses from turning monotonous and provide a human measure without anecdote. The villa’s geometry—rectangle with a hint of arch—supplies the few straight edges amid a world of curves, stabilizing the composition much as a sustained note stabilizes a melody.

Comparisons within the Early Nice Landscapes

Set “Eucalyptus, Mont Alban” alongside the year’s other landscapes and its role clarifies. Compared to “Landscape around Nice,” this canvas is more cropped and wooded, with the house acting as a color accent rather than an open vista. Compared to “Large Landscape with Trees,” it is warmer and denser, replacing broad atmospheric fields with a packed, ornamental canopy. Compared to “Landscape with Cypresses and Olive Trees,” eucalyptus crowns here are puffier, more cloudlike, and the darks are bolder, giving the scene a stronger graphic beat. The shared grammar—structural black, tuned greens, shallow space—ties them together as a coherent shift in Matisse’s practice.

Dialogues with Tradition

Cézanne’s lesson—to build landscape from constructive color planes—survives in the villa and in the way foliage is massed rather than blended. Japanese prints whisper in the bold contours and the clear stacking of planes. Post-Impressionist sensibility appears in the decisive stroke and the refusal of anecdote. Yet the whole is unmistakably Matisse: color as climate; black as architecture; simplification pursued until forms feel inevitable.

How to Look: A Guided Walk for the Eye

Enter at the lower right where bright greens and pinks flicker; climb the nearest trunk, noticing how its near-black thickens as it approaches the crown. Move left along the scalloped tops where sky pockets sparkle, then drop to the warm rectangle of the villa. Let your eye rest there before slipping behind another shaft into a velvety mass of dark leaves. Surface again through the cool blue shrub at center, then rise to the highest canopy where green shifts toward olive and brown. Finally, step back into the sky’s even field and feel its steadying breadth. Repeat the loop; the hillside’s rhythm becomes your breath.

Pentimenti and the Courage to Stop

Look closely and the painting reveals its revisions. A crown enlarged over a cooler under-pass; a trunk restated to widen its stance; a scrap of sky reclaimed between leaves; the villa warmed over a grayer first thought. Matisse leaves those seams visible. He halts not when surfaces are polished to anonymity but when relations snap into place. That earned inevitability is why the scene holds together with such calm authority.

Lessons for Painters and Designers

The canvas is a primer in economy. Use black as color to anchor light harmonies. State foliage as masses with varied edges instead of leaf piles. Seat architecture by temperature against its environment. Keep depth close to the plane so the image reads at a glance. Let the brush’s pressure change line weight to record gesture. Above all, engineer climate—an integrated set of relations—rather than chase effects.

Why It Still Feels Contemporary

A century later, the painting looks fresh because it aligns with modern eyes. Big shapes register immediately; the palette is sophisticated but quiet; process remains visible; space is shallow enough to echo graphic design, photography, and print. Most important, the work trusts a few true relations—dark trunks, warm house, cool sky—to carry sensation. That trust, disciplined and humane, is the essence of Matisse’s modernity.

Conclusion: A Grove Made of Relations

“Eucalyptus, Mont Alban” is not a catalog of trees; it is a construction of breathing relations—vertical against horizontal, warm against cool, dark against light. Matisse turns a hillside garden into a compact symphony where trunks keep time, crowns sing in measured intervals, and a small villa warms the chord. The result is a landscape you can inhabit with your eyes, one that offers steadiness without stiffness and air without emptiness. It embodies the promise of 1918: clarity after turmoil, serenity through structure, and light understood as a climate that holds.