Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

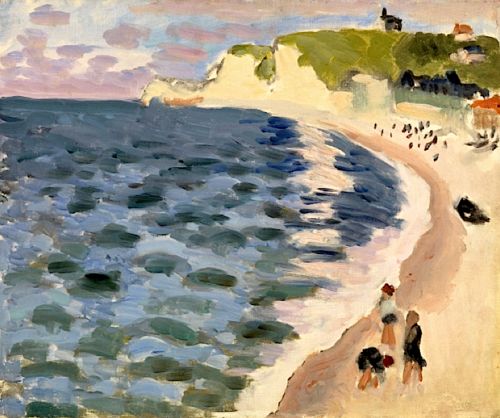

Henri Matisse’s “Etretat, The Sea” is a clear, confident summation of what he discovered on the Normandy coast: a shoreline that moves like a sentence, a sea that breathes in tiles of color, and a human presence reduced to a few telling notes. The view swings wide from a high vantage, letting the long surf line arc from the lower right to the chalk cliffs and green headland in the distance. On the sand, three foreground figures lean into the wind; further up the beach a scatter of dark gestures registers crowds and boats; out across the water a mosaic of blues and blue-greens carries the pulse of waves without a trace of fuss. With deliberate economy—broad strokes, living contours, and calibrated color—Matisse makes a place we can feel as much as see.

A Normandy Motif Tuned to Tempo

Etretat was a well-worn subject by 1921, famous for chalk cliffs and vaulting arches painted by Courbet and Monet. Matisse sidesteps spectacle. He gives us the headland and its chapel, but makes the sloping strand and the ocean’s lateral drift his protagonists. The curve of the beach becomes the sentence that guides the eye, punctuated by small commas of people and boats. The cliffs provide a radiant cadence near the horizon, but the tempo is set by water and shore. This shift from monument to movement is crucial to Matisse’s modern classicism: he turns a postcard landmark into a breathing rhythm of bands and intervals.

Composition Built on One Sweeping Arc

The picture’s architecture is almost diagrammatic in its clarity. One sweeping arc—the boundary where water meets sand—organizes everything. It begins at the lower right corner, rakes across the middle distance, and resolves beneath the chalk promontory. That single curve conducts the gaze through the entire painting. Broad, laterally brushed planes reinforce the arc: the sea as a left-hand wedge; the beach as a pale ribbon; the green headland as a counter-sweep above. Matisse places his three larger figures at the bottom right where the curve begins, turning them into a hinge between our space and the painted shore. Beyond them, clusters of tiny marks keep time along the beach so the arc doesn’t run away in one breath.

The Sea as a Living Mosaic

Matisse refuses to draw waves. Instead he constructs the water with a gridless mosaic of short, horizontal strokes—teal, cobalt, slate, turquoise—laid wet into wet. Each unit is a slightly different value and temperature, and the gaps between them remain visible. Those seams read like constant micro-motions on the surface. Near the shore, the strokes brighten and tighten, almost whitening as they mix with dragged surf; farther out they darken and lengthen. Because the “tiles” compress toward the horizon, the sea acquires depth without resorting to perspectival lines. The method is at once economical and exact: it does not describe water; it enacts it.

Surf and Sand: A Narrow Band of Light

The surf is a thin, continuous band drawn in one or two confident drags that let the canvas tooth catch paint irregularly, the perfect analogue for foam. Immediately inland, the sand flushes warm—pinked near the water, more buff where dry, and umbered where damp. The palette is lean but rich in modulation: a shell-pink seam, a small bruise of greyed violet in a hollow, a low gloss of lemon warmth where sun finds a fresh ripple. Because the beach is handled as one tilted plane, the viewer feels its slope and its breadth; it becomes, as often in Matisse, a stage on which figures and props can read with ease.

The Chalk Cliffs as a Light Machine

The high white cliffs and green mantle are stated with just enough articulation to establish mass and direction. Warm ochres and creams keep the chalk sunlit; cool violets are tucked into shadowed cuts to prevent a paper-flat silhouette. The green cap—a spring-grass register with hints of olive—rolls back toward the chapel that perches on the skyline like a small black note. The cliffs do not bully the painting; they complete the color climate. Their brightness bounces down into the surf and up into the underside of clouds, lifting the entire middle distance.

Figures as Tempo and Scale

In the foreground, three figures lean into sea air. They are painted as decisive abbreviations: a dark torso, a leg, a hat washed with red, a touch of peach for skin. They exist less as portrait likenesses and more as tempo marks—quarter notes at the start of a bar—giving a first beat from which the eye can count the beach’s curve. Further along the shore, groups condense into a scatter of commas. This is scale by rhythm rather than by measurement: the beach is long because we meet many beats before the curve resolves at the cliffs.

A Sky That Holds Without Competing

The sky carries a pale, cool register—lilac greys and purls of blue brushed laterally so they rhyme with the sea. Matisse keeps it quiet; there is no cloud theater to compete with shoreline and ocean. Near the horizon, small warm notes—faint rose and cream—bridge sky and cliff. This restraint keeps attention where the painting wants it: on the broad breath of water and the arc that frames it.

Brushwork That Preserves the Act of Seeing

Every passage confesses the hand: a loaded, dragged surf; overlapping rectangles in the sea; quick downward pulls for the green headland; small, firm dabs for figures. He stops early, when each passage “reads,” refusing polish so that the surface stays aerated. This candor is not negligence; it is a record of looking in tempo. The painting therefore transmits time—not just an image of a coast, but the speed and ease with which the coast came into focus for the painter.

Depth Through Overlap and Value, Not Rulers

Space is built by stacking planes and staggering values. The beach advances because its warm light pushes against the cooler sea; the headland sits behind because its edge rides above the beach and its value lowers into the sky; the figures at the front sit firmly because their darks and warms are strongest and their cast shadows kiss the sand. No orthogonals are needed. The viewer can walk this shore without ever tripping on a perspective grid.

Color Climate: Cool Breath, Warm Pulse

The painting’s climate is engineered by cool expanse against warm nerve. The sea’s cools—blues from greenish to steely—form the breath; the beach’s warms—peach, buff, small coppery pockets—form the pulse. The cliffs serve both: warm where they catch sun, cool where they turn away. This binary gives the canvas durable clarity. Any added color—a flash of crimson on a cap, a dark green in a distant plot, a black boat hauled high—reads as a bright accent against the climate rather than as noise.

The Ethics of Ease

Matisse wanted his art to function as a restorative environment. Here, ease is not laziness or sugar; it is a rightness among parts. The shoreline conducts the eye at a human pace; the sea breathes steadily; even the crowd is dispersed into a legible rhythm. The painter removes descriptive stress—no pebbles counted, no rigging diagrammed—so attention can rest on the coastal chord itself. The result is calm without vacancy, motion without agitation.

Dialogues with Impressionism and Fauvism

“Etretat, The Sea” converses with the coast as Monet left it—serial, atmospheric, optically alive—but trades the shimmer of countless touches for larger, franker units of paint. At the same time, Matisse carries forward the Fauvist conviction that color can bear structure. The sea’s mosaic is structural; the beach’s warm band is structural; the white of the cliffs is structural. It is an evolved simplicity: a classical grammar spoken with modern accents.

The Viewer’s Circuit: A Repeatable Walk

The painting provides a reliable walk for the eye. Most viewers start where the three figures gather, climb the surf band into the middle distance, pause at the tiny knots of people, then sail toward the white cliffs under the green cap. After a brief rest at the little chapel, the gaze slips left along the horizon and drops back onto the sea’s tiles, returning in a lateral drift to the lower left corner before curving shoreward again. Each lap yields incidents: a grey-violet seam in the water where depth drops; a lemon kiss along the cliff’s top; a darker, boat-like shape lodged on the beach; the faint blue shadow that lets the red hat pop. This smooth circuit is the painting’s hospitality.

Sensation Instead of Inventory

Nothing here is painstakingly catalogued, yet the place is unmistakable. The truth is carried by relationships: thin white pulled over blue reads as foam; warm chalk beside cool sky reads as cliff; a small black comma beside a pale plane reads as a person on sand. That economy opens space for the viewer’s memory of sea air, glare, and surf sound to join the picture. In this way, the painting is collaborative: it supplies the tuned structure; we supply lived sensation.

Human Work and Leisure Held in Balance

The presence of boats and crowds suggests not just scenic tourism but a working shore. Matisse assigns both work and leisure the same formal dignity: a black hull becomes a compositional anchor; strolling figures become scale marks; even the chapel, a cultural sign, reduces to a stabilizing dark accent on the skyline. The beach accommodates many uses, and the painting accommodates many readings without losing its central rhythm.

Light Distributed Like Air

The light is not a single device; it is a field. It falls broadly, heightening the cliff face, clearing the beach, and brightening the sea’s upper skin where strokes turn toward cyan. No cast shadow is forced to explain the time of day; rather, the values cohere into a believable climate. This approach keeps the canvas timeless in the best sense: it is evening and morning at once, or better, it is the sea’s perennial brightness filtered through a specific interval.

Why the Image Endures

The memory of this canvas sticks because its order is graspable at a glance and inexhaustible in detail. A single arc commands; a mosaic breathes; a bright cliff crowns; a handful of figures ground scale. The palette is limited but resonant, the brushwork candid, the mood sustained. You can return to it like to a favorite stretch of shore and find the same rightness waiting, renewed by new small findings each visit.

Conclusion

“Etretat, The Sea” demonstrates Matisse’s power to turn a well-known site into a lucid, durable harmony. He edits the coast to essentials—arc, plane, mass, mosaic—and then charges those essentials with breath through brush and color. The result is neither a literal report nor a decorative flattening; it is a lived climate in paint. The shoreline conducts, the sea inhales, the cliff reflects, and people take their modest, necessary place within the rhythm. This is modern classicism at full ease: an art of relations that leaves the viewer rested and alert.