Image source: wikiart.org

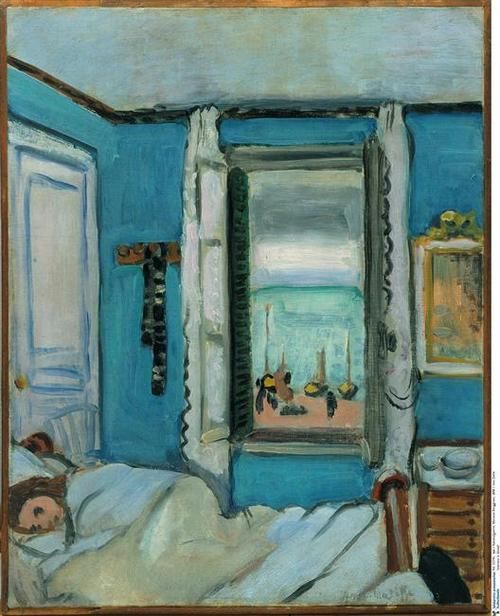

A Blue Room Listening to the Sea

Henri Matisse’s “Étretat Interior” (1920) is a hushed, lucid picture that binds a private room to a public horizon. A woman sleeps in a white bed at the lower left, while the center of the canvas opens onto a tall window where sky, sea, and a line of small boats sit in banded color. The walls, door, and even the mirror’s frame are pitched to a serene blue; white curtains and bedding soften every edge. Nothing in the scene shouts for attention, yet the composition stays magnetic because interior stillness and exterior motion share a single breath. Matisse offers a model of how to make a room feel alive without filling it with incident—by tuning planes, colors, and touches so precisely that the viewer can sense both the weight of sleep and the salt of the Channel air.

Context: Étretat and the 1920 Return to Calm

The year places this canvas within Matisse’s post-war classicism, a period when he refined a language of clarity after the earlier storms of Fauvism and Cubism. Étretat, on Normandy’s coast, had already been made canonical by Courbet and Monet; Matisse visited in 1920 and produced a suite of coastal paintings—cliffs, boats, fish on the shingle—alongside interiors that fold the sea back into the domestic sphere. In “Étretat Interior” the artist tests how much of the coast a room can safely contain. Instead of dramatizing the famous cliffs, he evocatively frames a narrow view where bands of turquoise and gray carry the entire weather. The painting belongs to the same family as his Nice interiors in which windows and doors act as hinges between enclosure and horizon, but here the palette cools and the mood becomes more intimate, closer to a lullaby than a balcony conversation.

Composition: Bed, Window, and the Geometry of Threshold

The armature of the picture is an L-shaped arrangement. The horizontal of the bed and the sleeping figure runs along the bottom left, while a vertical shaft of window and shutters rises at center, slightly off to the right. These two elements—repose and outlook—meet at the room’s corner, tightening the composition without making it cramped. A blue door on the far left repeats the vertical and implies another exit that remains closed; a small dresser and a gilt mirror at the right echo the bed’s horizontal, completing a quiet grid. The eye moves in a simple circuit: across the sleeper’s pale shape, up the white curtains to the window, out to the bands of sea and sky, then back through the cool blue walls to the patient rectangle of the door. Every passage is measured, and every threshold is announced with tenderness.

Color: A Symphony in Blues and Whites

Color secures the mood. The room is bathed in a spectrum of blue—from chalky turquoise to deeper, cooler notes—interrupted by the whites of bedding, curtains, and painted wood. This pairing turns the interior into a climate rather than a set of tinted objects. The blues keep the space calm and breathable; the whites provide circulation, like drafts of air moving through cloth. Within this restrained chord, small accents carry special weight: the warm brown of the bedposts and dresser knobs, the ocher sparkle of a mirror frame, the soft flesh tones of the sleeper’s face. Outside the window, Matisse bands the sea into green-blue and the sky into milky gray, separated by a pale horizon, so that exterior color harmonizes with the room rather than competing with it. The whole palette feels like a single exhale.

Light and the Atmosphere of Rest

There are almost no hard shadows. Illumination is conveyed by value steps and by the way the white passages lighten wherever fabric creases or wood catches a thin edge of paint. It suggests an overcast morning or the even light of late afternoon—weather that softens edges and lets color settle into its home values. The bedding glows without glare, the shutters stay legible without blackness, and the small still lifes of brushes or bottles on the sill sit in a cool wash. Light becomes the guarantor of rest; it removes urgency from the scene and confers a gentle dignity on the sleeper.

The Figure: Sleep as Anchor and Measure

Matisse’s sleeper is not anatomically elaborated, yet she is deeply present. A few strokes define hair around a cheek; a delicate contour gathers shoulder, elbow, and blanket into one soft triangle; a blush of pink warms the face. The sleeper’s role is compositional rather than narrative. Because we intuit the human scale, her body calibrates everything else—the height of the window, the breadth of the bed, the width of the wall. She is also the painting’s ethical center: a person who can rest safely in a room that listens to the sea. Matisse’s longstanding theme of repose finds a new key here, less odalisque than household, less display than shelter.

The Window: A Painting Inside the Painting

The view through the opening is treated as a separate, condensed canvas. Matisse divides it into simple bands—parapet, row of small boats and figures, a broad field of turquoise sea, a narrow strip of pale sky—and flanks it with shutter blades whose dark hinges articulate the vertical. These shutters are painted with tactile relish: a slightly darker green down their centers, lighter edges where wood catches light, and scalloped inner edges on the curtains that repeat, in miniature, the soft waves beyond. The outside is neither anecdotal nor spectacular; it’s a distilled seascape whose simplicity allows it to refresh the interior like a glass of water placed on a bedside table.

Brushwork, Edges, and the Material Surface

The canvas is alive with different touches that tell you what each thing would feel like. Bedding is laid in with quick, curving swipes that make the surface feel sprung and warm. Walls and door receive long, even strokes so that paint sits like a thin coat over plaster. Shutters and frame are stated more decisively, their edges firm enough to anchor the composition but soft enough to keep the harmony. The boats outside are no more than flicks of darker paint; the sea is a set of horizontal pulls that leave tiny ridges, like ripples. Matisse allows pentimenti to remain—slight adjustments around the window and the bed—so the painting retains the sensation of having been built in real time, a quality that brings the quiet to life.

Space Kept Honest to the Canvas

Although the picture describes depth, it remains true to the flat surface. The window is centered and frontal, the bed is a broad wedge that rides the bottom edge, and the walls are planar fields with little modeling. The effect is both roomlike and page-like. You are invited to imagine stepping into the space, but you are never asked to forget that you are looking at a constructed harmony of rectangles and bands. This commitment to the picture plane gives the image its serenity; nothing theatrical pulls you into a maw of perspective, and nothing decorative floats you away.

Pattern, Ornament, and the Usefulness of Things

Matisse is sparing with ornament here. A scalloped border on the curtains, a ribbon or scarf hanging from a peg, and the gilt mirror are sufficient to make the room feel inhabited. The mirror is especially telling. Rather than acting as a dramatic reflector, it behaves like a warm counter-shape to all the blue—an oval sun in a cool climate. The dresser’s stacked drawers and the bedpost’s blunt finials keep the domestic note present without clutter. Everything is functional, and because it is functional, it is beautiful.

Sound, Time, and Weather

Though silent, the painting evokes a soundscape: muffled surf outside the shutter, the soft drag of curtain against rod, the faint creak of boards as someone recently moved. Time reads in layers. Immediate time is the sleeper’s breath; cyclical time is the tide just beyond the sill; longer time is the season marked by the heavy bedclothes and the cool palette. Matisse lets these tempos coexist without parable. The room is not a symbol; it’s a vessel for daily life set within larger rhythms.

Human Presence Without Storytelling

There is no overt narrative. We do not know why the woman sleeps or when she will wake. The painting’s refusal to explain is a form of respect; it allows the figure her privacy and the viewer the space to attend to color and relation. The sleeping body, the window, and the sea are enough. They form a triad—self, shelter, and world—that Matisse returns to in many guises. Here the triad is at its quietest, and therefore at its most persuasive.

Dialogues with Étretat and with Modern Interiors

Because Étretat was famously painted by Monet, any work set there converses with the Impressionist legacy. Matisse’s reply is austere and tender. He rejects optical shimmer in favor of firm bands of color; he trades cliff spectacle for domestic confidence. The painting also speaks with contemporaries like Bonnard and Vuillard, whose patterned rooms embrace figures. Matisse diverges by paring the décor back and letting a single cool chord set the mood; clarity replaces density as the route to intimacy. In the context of his 1920 coastal canvases—boats on the beach, cliffs and arches—this interior offers the shoreline from the perspective of rest.

Iconography of Threshold, Dream, and Protection

Windows and doors in Matisse are never merely architectural. They render the act of looking itself. In “Étretat Interior” the sleeping figure does not look; the room looks for her. The window watches the sea; the sea’s bands report the weather; the shutters modulate exposure. The painting becomes a picture of protected dreaming, of the mind’s ability to hold the outside world without leaving the bed. It is not sentimental. Protection here is coloristic and spatial, a matter of right placement and temperature.

Lessons in Color and Spatial Design

The canvas is a concise primer in how to orchestrate a cool interior. Set a dominant hue—in this case, blue—across multiple surfaces so the space speaks one language. Use whites as circulation, where air and light can move. Reserve warm accents for human points—face, wood, gilt—so the viewer’s attention lands with purpose. Keep the exterior simple and in harmony with the interior chord. Build depth with thresholds rather than with heavy perspective, and assign each zone a distinct touch to deliver texture sensually instead of verbally. The result is a room that reads instantly from a distance and deepens at arm’s length.

Why the Picture Endures

“Étretat Interior” continues to feel fresh because it solves permanent problems with generous simplicity. It shows how to unite intimacy and openness, how to let a single color carry mood without monotony, and how to make a world with a handful of objects that respect a person’s sleep. The painting does not insist on itself; it offers a space one could enter, occupy, and leave replenished. In an era that often equates modernism with rupture, Matisse proposes a modernism of care.

Conclusion: A Room, a Window, a Sea

At heart, this canvas is a balanced sentence composed of three nouns. Room: blue, ordered, gently lit. Window: vertical, banded, a clear invitation. Sea: distant, rhythmic, steadying. The sleeping figure ties them together, giving scale to the room and purpose to its openness. With quiet mastery, Matisse makes color do the work of architecture and attention do the work of narrative. “Étretat Interior” is therefore more than a depiction of a morning on the Normandy coast; it is a compact philosophy of how to live well with light, water, and rest.