Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Iberian Allure In Matisse’s Nice Period

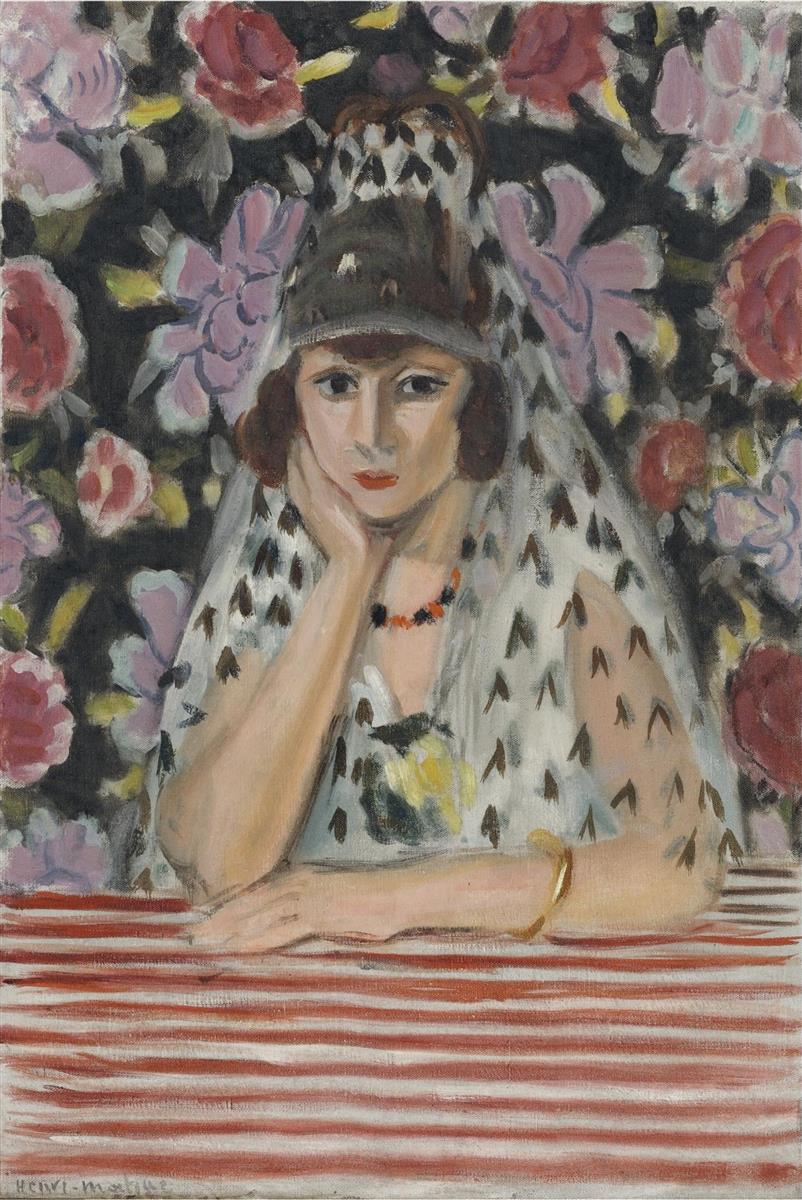

Henri Matisse painted “Espagnole” in 1922, in the midst of his Nice years when he turned again and again to intimate interiors, patterned textiles, and models in evocative costumes. In the wake of the First World War, Matisse sought calm intensity rather than shock; his studio became a small theater where light, fabric, and figure could be orchestrated with exquisite control. Spanish themes had gripped European culture since the nineteenth century, and Matisse had long admired Iberian painting and the decorative traditions he encountered in the Mediterranean world. In this portrait the idea of “Spanishness” is distilled into signs—a lace-like mantilla, a dark peineta-style headpiece, bold jewelry, and a face whose direct gaze carries poise. The result is not a document of national costume so much as a modern meditation on character through pattern.

Composition As A Tight Stage Of Pattern And Presence

The composition is built frontally and close, a bust-length portrait pressed up against the picture plane. A floral tapestry fills the entire background with a dense field of pinks, mauves, and crimson blossoms on dark ground. In front, a striped tabletop runs horizontally across the lower edge like a stage apron, red bands alternating with pale ones to create a rhythmic base. Between these two assertive patterns sits the figure, her chin resting in her right hand, her left arm stretched along the table. The pose is classical in its triangular stability, yet the patterns around her electrify the stillness. Matisse locks the elements together by aligning the sitter’s forearms with the stripes, letting the vertical fall of the veil negotiate between the horizontal table and the blooming wall. The painting reads at once as portrait and as a precise architecture of ornament.

The Face As Anchor And Locus Of Gaze

Although patterns dominate the field, the face is the anchor. Matisse simplifies it to broad, luminous areas, allowing the eyes, brows, and mouth to carry expression. The pupils are set cleanly within almond-shaped sockets; the brows are concise arcs that give the gaze intent without severity. The mouth is a small, firm note of warm red that punctuates the center of the painting. Minimal modeling around the nose and cheeks suffices to turn the head gently in space. By refusing fussy description, Matisse heightens the authority of the gaze; we meet a person rather than a collection of traits. The hand supporting the chin doubles this authority: its wedge shape reprises the jawline and underscores contemplation.

The Mantilla And The Semiotics Of Costume

What makes the image read as “Espagnole” are the carefully placed signs of costume. The veil descends in translucent white with repeated, arrow-like black marks that read as embroidery or appliqué. It frames the face like a theatrical proscenium while softening the floral storm behind her. A dark, crested headpiece peeks from beneath the veil, echoing the silhouette of a peineta comb. A simple necklace of warm beads and a single gold bracelet supply accents that confirm the portrait’s worldly elegance. Rather than catalog historical detail, Matisse treats costume as a vocabulary of shapes and tones that defines character: composed, alert, and slightly ceremonial.

Color Chords And The Balance Of Warm And Cool

The palette pivots on three families of color: the red-pink spectrum of lips, flowers, and stripes; the cool grays and dim violets that structure the veil and background shadows; and the warm flesh notes that illuminate the face and arms. The red stripes below act like a metronome, keeping time for the eye as it moves across the canvas. Their warmth rises into the roses and returns through the mouth and beads, binding the composition with a circulating pulse. Cool grays temper this heat, especially in the veil and in the shadowed petals. Matisse’s control is evident in the delicate flesh transitions: soft apricot warms into cooler halftones at the wrist and jaw, keeping the figure alive against the clamorous field.

Drawing Inside The Paint

Matisse’s line is assertive yet forgiving. The contour of the arms is stated in supple, elastic strokes that thicken at elbows and taper at the wrist. The facial features are drawn with a brush, not a pen, allowing edges to breathe. The floral outlines behind the sitter are only as firm as the composition requires; many petals are merely suggested by quick turns of the brush. The veil’s marks, each a pointed lozenge, march down the shoulders with enough regularity to signal pattern while adopting minute variations that keep the surface from freezing. Drawing and color are not separate acts here—the line is saturated with pigment, so that form arises from hue as much as from outline.

Pattern Against Pattern And The Problem Of Figure/Ground

Few artists balanced figure against ornament as deftly as Matisse, and this portrait is a lesson in that art. The background threatens to consume the sitter: roses crowd every inch, their dark ground pressing forward like a night sky full of blossoms. The striped table threatens to slice the composition into bands. The veil solves both problems. As a semi-transparent plane, it filters the floral energy, reducing the background’s aggression where it crosses the shoulders. At the bottom edge, the sitter’s arms interrupt the stripes, humanizing their mechanical rhythm. The figure thus emerges not by isolation but by negotiation, her presence defined as the place where patterns come to rest.

Light As A Soft Veil Rather Than Spotlight

There is no theatrical spotlight; light here is the even, indoor brightness of a studio where curtains have muffled glare. Matisse renders it as gentle clarity—a quiet shine on forehead and nose, pale slips of light on knuckles and bracelet, a subdued sheen along the table stripes. Shadows are cool and breathable, never heavy. This modest illumination preserves the authority of color. Reds, grays, and fleshes retain their full temperature, and the portrait’s mood remains contemplative rather than dramatic.

Psychological Poise And The Ethics Of Looking

The sitter’s hand-to-chin pose suggests pause and inwardness, yet the gaze meets ours without coyness. The painting conducts the viewer’s attention toward the face and then lets it circulate across veil, bracelet, and tabletop before returning to the eyes. Because Matisse has eliminated anecdotal distractions—no elaborate interior, no window, no props beyond the table—the encounter remains ethical and steady. We are invited to look long, not to pry. The portrait respects its subject by embedding her in a visual order as dignified as her expression.

The Spanish Image In Modern Paris

Around 1920, Spanish imagery coursed through Parisian culture—in theater, fashion, and painting. Matisse absorbed this current not by imitation but by translation. “Espagnole” draws on the allure of a mantilla and on the reputation of Spanish painting for gravitas and strong contrasts, yet it refuses the darkness and theatrical chiaroscuro associated with that tradition. Instead he marries Iberian signs to the high-keyed, breathable atmosphere of his Nice period. The portrait becomes a cosmopolitan emblem: a modern woman fashioned through the lens of a theme rather than confined by it.

The Table Of Stripes As Modern Device

The striped table deserves special attention. It is both furniture and compositional machine. The regular alternation of red and white establishes a horizontal tempo that counters the organic irregularity of the flowers. The stripes also flatten the foreground, pushing the figure forward and tying the portrait to the shallow picture plane prized by modern painters. Within this modern flatness, Matisse still introduces tactile nuance: the reds are not uniform; they thicken and fade with the brush’s pressure, so the mechanical becomes humanized.

Jewelry, Hands, And The Small Grammar Of Accents

Two small accents articulate the sitter’s presence: the beaded necklace, which echoes the floral reds while stringing a line across the chest, and the single gold bangle, which catches a slender stroke of light and curves like a half-note along the lower edge. The hands, one supporting the face and one resting along the table, speak the language of repose. They are not meticulously modeled; they are shaped with a few graceful planes and small cool shadows, enough to imply warmth and calm. These elements—jewelry and hands—act as punctuation in the sentence that is the portrait.

The Mantilla’s Marks And The Idea Of Translation

Those crisp, arrow-shaped marks scattered across the veil exemplify Matisse’s method of translation. Instead of rendering lace thread for thread, he invents a sign—simple, repeatable, and legible at distance—that conveys the impression of ornament and texture. Each mark is similar but not identical, a variability that allows the veil to shimmer. The device serves both illusion and abstraction: it suggests material while preserving the painting’s integrity as a patterned surface.

Relation To Earlier And Later Portraits

Compared with Matisse’s Fauve portraits of 1905–06, “Espagnole” is more tempered in palette and more controlled in line, yet it shares their essential belief in color as character. Compared with the later, extremely simplified heads of the 1930s and 1940s, it is richer in pattern and fuller in paint. The work stands at a hinge point in his development, when the lushness of Nice interiors met a growing desire for clarity. One can already feel the later economy in the face and hands, even as the background indulges a garden of brushwork.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Rhythm

The painting choreographs a precise path for the eye. We begin at the vibrating stripes, ascend the arm to the gold bangle, climb the diagonal of the forearm to the chin, pause at the lips and eyes, then drift outward along the veil where the black marks lead us into the floral field. From there we return to the center, as if pulled by gravity back to the gaze. Each circuit confirms the portrait’s rhythm: measured horizontal beats below, syncopated blossoms behind, and a steady human tempo in the face.

The Power Of Omission And The Pleasure Of Clarity

Everything unnecessary has been set aside. There is no detailed interior, no cast shadow cutting across the table, no glittering lace rendered thread by thread. What remains—face, veil, flowers, stripes—has been tuned to create clarity. This clarity is pleasurable not because it is simple, but because it is exact. Each note plays its role; each decision carries weight. The portrait lingers in the memory the way a melody does—recognizable in a few intervals even after the details fade.

Emotional Weather And Lasting Resonance

The emotional weather is composed, lucid, and quietly radiant. Reds convey vitality without fever; grays cool the scene without draining it. The sitter’s expression holds curiosity and reserve in equal measure. The painting resonates today because it models how identity can be staged without spectacle. In an age that often equates intensity with noise, “Espagnole” shows how a person can command a room through poise, rhythm, and a finely balanced chord of color.