Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions

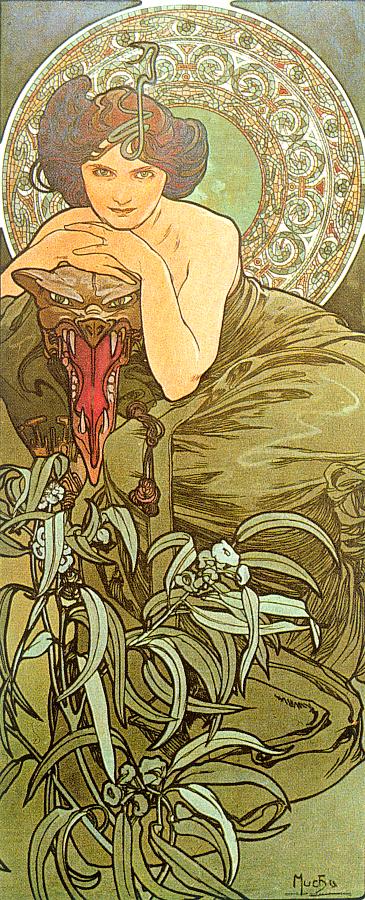

Alphonse Mucha’s “Emerald” (1900) unfolds like a jeweled reliquary opened in lamplight. A woman leans forward with her chin resting on the back of one hand, the other arm bracing a carved armrest whose mask-like ornament introduces a flash of red within an overwhelmingly green world. Behind her, an intricate circular mandala glows like an illuminated page or a gemstone seen from within. Around her knees and spilling toward the viewer, mistletoe weaves a pale constellation of berries among long, ribboning leaves. The mood is poised and intimate, luxurious yet inward-facing—an emblem of the emerald’s reputation for clarity, renewal, and protective calm.

Historical Moment

By 1900 Mucha had refined the tall decorative panel as his signature medium, translating seasons, hours, flowers, and gemstones into personifications for modern interiors. “Emerald” belongs to his cycle devoted to precious stones, where each print embodies the character of a gem through color, motif, and attitude rather than literal depiction. The panel exemplifies the Art Nouveau conviction that beauty and meaning can be fused into a single, legible design—one that could be reproduced as a color lithograph and lived with every day.

The Language Of The Gem

Emerald carries a rich symbolic burden: spring, constancy, healing, and the lucidity of vision. Mucha communicates those qualities not by painting a faceted crystal but by orchestrating a green tonal universe, seating his model before a halo that resembles a cut stone’s interior geometry, and entwining the foreground with mistletoe, a plant sacred in Celtic myth and evergreen in winter. The entire image behaves like a gemstone translated into human scale—the woman is the gem’s conscience, the halo its fire, the flora its living aura.

Composition And Architectural Calm

The format is a narrow vertical rectangle whose architecture is quietly decisive. A radiant circle anchors the upper half, framing the head and shoulders; a massive block of drapery stabilizes the center; and the mistletoe’s long arcs knit the lower field into supple order. The figure’s forward lean presses gently toward the viewer without breaking the plane, while the carved armrest interposes a small, theatrical proscenium between us and her. The composition achieves a paradox Mucha loved: abundance contained by geometry, movement restrained by frame.

The Mandala As Facet And Halo

Mucha’s circular backgrounds often serve as halos, but here the circle is also a jewel. Interlaced bands, knots, and concentric lattices spin outward, catching pinks, olives, and pale greens in a pattern that suggests light refracting through facets. The design nods toward Celtic illumination—appropriate given mistletoe’s Druidic associations—yet remains fully Art Nouveau in its rhythmic, whiplash arcs. The circle dignifies the sitter while declaring the panel’s theme: a world seen through green glass.

Gesture, Gaze, And Persona

The model leans on the armrest in a pose that is at once relaxed and engaged. Her chin rests lightly, her shoulders open, and her eyes meet ours directly. Unlike Mucha’s dreamier profiles, this frontal exchange projects confidence and intelligence. A single flower crowns her hair, and a slender hairpin rises like a staff, giving a vertical accent that answers the panel’s height. The persona is not a mythic goddess so much as a modern sibyl—the living voice of the emerald’s calm clarity.

The Carved Armrest And The Red Counterpoint

The armrest is a small masterpiece of contrast. Its sharp geometry and mask-like carving introduce angles within a composition dominated by curves. Its warm reds and russets, with hints of gold, puncture the dominion of green, making the emerald world feel richer for the interruption. Mucha often inserts such a counter-hue to keep harmony from becoming monotony; here the red reads like the stone’s inner fire, a complementary spark that makes green sing more vividly.

Mistletoe As Emblem

At the base, mistletoe unfurls with forked stems and pale berries. The plant’s evergreen resilience and ritual history dovetail with the emerald’s symbolism of protection and renewal. Mucha’s treatment is decorative rather than botanical: leaves twist in long S-curves, berries gather like small moons, and stems braid themselves into a visual bass line that grounds the figure. The flora does not merely accompany; it participates in the portrait, extending the subject’s presence outward into the space of the viewer.

Color Harmony And Emotional Temperature

The palette ranges across olive, sage, celadon, and sea-glass green, moderated by earthy browns and enlivened by controlled reds. Mucha avoids harsh contrast; instead he builds harmony through near-neighbor hues and subtle temperature shifts. Highlights are warm rather than icy, so the panel glows instead of glittering. The result is an atmosphere that feels protective and lucid—fully in keeping with emerald’s reputation as a stone for clear seeing and steady feeling.

Line, Contour, And Ornamental Intelligence

Mucha’s dark contour lines are firm but elastic, enclosing areas of flat color that lie as smooth as enamel. Inside those boundaries, he uses lighter interior lines to articulate folds of drapery, strands of hair, and the crisp edges of leaves. The whiplash curve—a signature of Art Nouveau—flows through mistletoe stems, hair, and sash without ever degenerating into aimless flourish. Line here is grammar: it keeps ornament articulate and emotion readable.

Drapery And The Architecture Of Weight

The woman’s gown is a block of green satin that pools and lifts with sculptural conviction. Mucha simplifies the folds into broad planes, then accents their crests with narrow highlights to suggest sheen. The drapery’s mass acts like a pedestal for the upper body and like a quiet wall against which the lively foreground plants can play. By giving the cloth architectural gravitas, he dignifies the theme of constancy associated with both mistletoe and emerald.

Space, Depth, And Decorative Flatness

The panel operates in shallow space: chair, figure, halo, and plant occupy adjacent layers that never dissolve into deep illusion. This controlled flatness is a practical concession to lithography and a conceptual choice that keeps meaning front and center. Space is the field on which symbol and design are arranged, not a world to wander into. The shallow depth makes the viewer’s encounter frontal and ceremonial.

Lithographic Craft And Velvet Surface

As a color lithograph, “Emerald” relies on separate stones or plates for each hue, perfectly registered. Mucha composes with that craft in mind: broad, unbroken color fields; crisp outlines; and patterns that can be printed cleanly without muddying. The method yields a velvety surface, neither glossy nor dull, that absorbs light softly—the visual equivalent of a gemstone held in the hand rather than flashed under stage lamps. That tactility is central to the print’s appeal.

Ornament And Order In Balance

The panel is lush with detail—the latticework halo, the carved armrest, the tangle of mistletoe—but never feels busy. Mucha achieves this by anchoring ornament to large, simple masses: circle, figure, drapery block, plant field. The eye can rest on these forms while enjoying the micro-patterns that play across them. Ornament becomes a way to think rather than a way to decorate, a structure for attention rather than a distraction.

The Face As Locus Of Meaning

Mucha models the face with great economy: a few gentle transitions establish cheek, brow, and shadow; the mouth is calm; the eyes bright without glare. Set against the dense pattern of the halo, the face reads as the gem’s living facet. There is a quiet sovereignty in the expression, a suggestion that clarity is not coldness but composure. The woman does not seduce; she steadies.

Dialogue With Other Gem Panels

Compared with “Amethyst,” whose violets drift toward reverie, “Emerald” is clearer and earthier. Its greens are tempered by olive and moss; its reds add warm contrast; its gaze is more direct. Where amethyst whispers inward, emerald speaks outward with calm authority. The difference illustrates how Mucha tuned gesture, flora, and palette to the unique temperament of each stone while preserving a consistent structural language of circle, figure, and floral base.

Cultural Resonances And Domestic Use

These panels were designed for modern apartments, where tall, narrow spaces cried out for elegant decoration. “Emerald” would have harmonized with wood tones, brass fittings, and plant-filled parlors, offering an emblematic calm to the room. Its Celtic inflection would have appealed to turn-of-the-century taste for historical motifs, while its modern face and fashionable hair rooted it in the present. The work is both an ornament and a proposal for living with composure.

Rhythm And Visual Music

Mucha composes like a musician in a minor key warmed by sun. Long arcs of mistletoe set up a legato flow from lower left to center. The diagonal of the leaning figure carries the eye to the face, where the circular halo holds a sustained chord of pattern. Small accents—the tassel by the armrest, the flower in the hair, the white berries—play like grace notes against the larger melody. The whole panel reads as a phrase that resolves into stillness at the gaze.

Allegory Without Anecdote

No story is narrated. The panel communicates through equivalence: green equals emerald, mistletoe equals evergreen vitality, halo equals radiance, forward lean equals engagement. This economy of signs makes the image instantly legible to a wide audience and grants it longevity. Without a tether to a particular myth or episode, the emblem can live wherever viewers bring their own associations to it.

Why “Emerald” Endures

The endurance of “Emerald” lies in its union of mood and craft. The print offers a complete atmosphere—clear, protective, verdant—delivered through a language of disciplined line, controlled color, and balanced ornament. It satisfies the eye and steadies the mind. In showing that a gemstone can be translated into posture and pattern, Mucha confirms the promise of Art Nouveau: that beauty, thoughtfully designed, can make ideas visible and livable.

Conclusion

“Emerald” distills a gemstone’s character into a world of green coherence. A poised woman leans toward us, framed by a faceted halo and grounded by mistletoe’s evergreen curls. Reds kindle the greens, line clarifies abundance, and lithographic craft wraps everything in a velvet calm. The panel is not merely decorative; it is a portrait of clarity, an emblem of steadiness that still feels at home on a wall more than a century after it was made.