Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

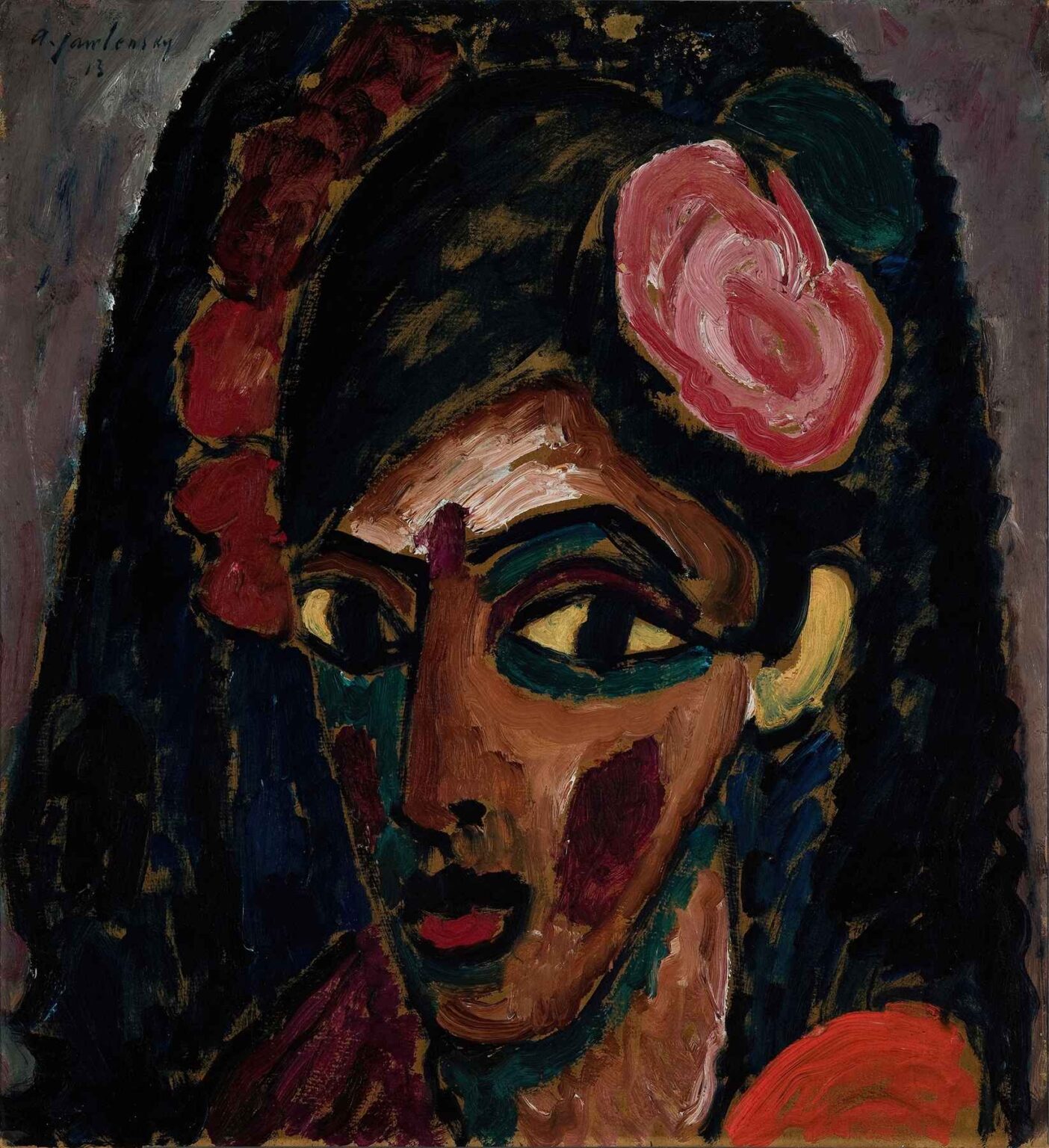

Alexej von Jawlensky’s “Egyptian Girl” (1913) stands as a vivid testament to the artist’s exploration of expressive color, spiritual resonance, and non-naturalistic form in the years leading up to World War I. Painted during Jawlensky’s mature period in Murnau, Bavaria, this portrait transcends mere likeness to convey an inner intensity through distorted features, bold chromatic contrasts, and a stark, flattened space. In crafting this analysis, we will examine the historical and artistic context of early Expressionism, Jawlensky’s evolving aesthetic theories, the formal composition of the painting, his radical use of color and light, the work’s iconographic dimensions, his distinctive technique and brushwork, the painting’s place within his broader oeuvre and Expressionist circles, and its enduring emotional and spiritual impact. Through these lenses, “Egyptian Girl” emerges not simply as a striking portrait but as a milestone in the transformation of European avant-garde art.

Historical and Artistic Context

By 1913, European art was in ferment. The revolutionary color experiments of the Fauves and the fragmented forms of Cubism challenged conventions, while German artists sought to awaken emotional and spiritual depths through heightened expression. Jawlensky, a Russian émigré and former student of Marianne von Werefkin, became a leading figure among the Munich-based Der Blaue Reiter group. His turn toward abstraction and symbolic use of color reflected a shared desire to move beyond representation into realms of inner vision. Travel and exposure to non-Western art, including Indian miniature painting and African masks, further liberated Jawlensky from academic naturalism. In this milieu, “Egyptian Girl” occupies a pivotal moment: the fusion of portraiture with pure color fields and simplified form that would culminate in his later “Abstract Heads.”

The Artist: Alexej von Jawlensky

Born in 1864 near Saint Petersburg, Alexej von Jawlensky trained briefly at the Imperial Academy before military service and subsequent defection to Munich in 1896. There he found intellectual camaraderie with Wassily Kandinsky, Gabrielle Münter, and Franz Marc. Jawlensky’s early work exhibits the sinuous lines and jewel-like palette of Russian Symbolism, but by the 1910s he had shifted toward a more reductive, emotional style—eschewing detailed modeling for broad, flat planes of contrasting color. In correspondence, he emphasized painting as a spiritual practice, stating that the “true face” emerges only when the artist dissolves personal preconceptions. “Egyptian Girl” exemplifies this credo, transforming its subject into a vessel for color-driven spirituality rather than a mere physical likeness.

Subject and Iconography

At first glance, the sitter’s identity remains anonymous. The title “Egyptian Girl” may reflect Jawlensky’s fascination with “exotic” physiognomies or his interest in archetypal types rather than a specific individual. Her name unknown, she becomes an icon—an idealized feminine presence imbued with mystery. The triangular band of light across her forehead and the curving lines of her headdress suggest ancient Egyptian reliefs, while the stylization of her almond-shaped eyes evokes the masks and faces of African sculpture. Through this selective reference to non-Western art, Jawlensky universalizes his portrait: the sitter’s cultural specificity gives way to a transcultural expression of inner intensity.

Composition and Spatial Structure

Jawlensky arranges the figure against a shallow, nearly undefined background of greenish-blue and gray, isolating her form and heightening its monumentality. The portrait is tightly cropped—only the sitter’s head, neck, and shoulders are visible—drawing attention to the direct, almost confrontational gaze. Subtle asymmetries—her head tilted slightly, one shoulder raised—break any static frontal pose, lending a dynamic tension. The composition centers on the vertical axis of her nose and mouth, while diagonal accents—the curve of her headdress, the angle of her jaw—guide the eye through the painting. This interplay of vertical and diagonal lines, combined with the stark flattening of space, creates an emotive stillness characteristic of Jawlensky’s best Expressionist portraits.

Color Palette and Emotional Resonance

Color in “Egyptian Girl” is not descriptive but deeply symbolic. The artist applies patches of ochre, rose, vermilion, deep violet, emerald green, and burnt sienna in broad, unblended strokes. Against a muted background, these vibrant hues vibrate in contrast, activating the sitter’s face as a living chromatic field. Jawlensky believed that colors corresponded to spiritual or psychological states: red for vitality, blue for introspection, yellow for warmth. Here, the interplay of red and green around the eyes and cheeks suggests a tension of passion and reflection; the band of yellow across the forehead becomes a luminous crown. By deliberately eschewing natural skin tones, he elevates the portrait to an expression of inner life—each color a signpost to the sitter’s unspoken emotions.

Light and Shadow as Symbol

Rather than conventional chiaroscuro, Jawlensky uses color to model form. Light appears as warm yellow-orange planes, while shadow is denoted by deep purples and blues. The high contrast between these color zones creates a dramatic, almost theatrical effect, yet the transitions remain abrupt rather than gradated. This stylization draws attention to the paint itself, turning surface contrasts into metaphors for the subject’s psychological complexity. The glow of light on the forehead and cheekbones suggests an inner luminosity, reinforcing the painting’s spiritual undertones. Shadows, conversely, mark areas of introspection or guardedness, particularly around her mouth and jaw.

Technique and Brushwork

Jawlensky executed “Egyptian Girl” in oil with a confident, brush-driven hand. He laid in large areas of pure pigment, sometimes with a palette knife, before refining edges with brushstrokes that carry visible directional energy. His handling is impasto in places—thick ridges of paint that catch light and cast micro-shadows—while other areas are scumbled or lightly dragged to reveal underlayers. The freedom of his stroke reflects an emphasis on immediacy and authenticity of feeling: mistakes are not concealed but integrated into the expressive whole. Infrared studies reveal that Jawlensky’s initial drawing was sparse, allowing the paint itself to define form and expression. This painterly boldness aligns him with fellow Expressionists, yet his distinctive focus on the isolated face sets him apart.

Comparative Perspectives: Expressionism and Beyond

Compared with his friend Wassily Kandinsky’s abstract compositions from the same period, Jawlensky’s “Egyptian Girl” retains a vestige of figuration while moving decisively away from realism. In contrast to the psychologically charged portraits of Egon Schiele, which emphasize angularity and sexual tension, Jawlensky’s sitter conveys calm intensity and a meditative presence. His affinities with Henri Matisse appear in his use of color to delineate form, yet unlike the fauvist concern with decorative pattern, Jawlensky’s palette serves an inner, spiritual scheme. Within Der Blaue Reiter circles, “Egyptian Girl” exemplifies the middle path between figural portraiture and pure abstraction—anticipating his later, more abstracted “Mystical Heads” of the 1920s.

Emotional and Spiritual Impact

The power of “Egyptian Girl” lies in its dual engagement: it confronts the viewer with an arresting, vividly colored visage, yet invites inward reflection on the nature of personality and soul. The sitter’s unsmiling mouth and large, dark eyes convey a quiet dignity, even solemnity. One senses both presence and distance, an individual’s humanity and an archetype’s universality. Jawlensky’s choice to flatten space and heighten color rejects any illusion of objective reality, prompting viewers to respond not to a social portrait but to a spiritual encounter. In this sense, “Egyptian Girl” functions as a modern icon, a focal point for contemplation of inner life.

Legacy and Relevance

Alexej von Jawlensky’s “Egyptian Girl” represents a watershed in the history of Expressionist portraiture. By integrating influences from non-Western art, early abstraction, and Russian Symbolism, he crafted a mode of portraiture that foregrounds color as emotion and form as spirit. Later artists—from abstract colorists like Mark Rothko to contemporary portrait painters exploring psychological depth—have drawn on Jawlensky’s innovations. Today, “Egyptian Girl” is recognized not only as a highlight of the German Expressionist movement but also as a precursor to the 20th century’s broader exploration of art’s capacity to reveal inner realities.

Conclusion

In “Egyptian Girl” (1913), Alexej von Jawlensky transcends the boundaries of traditional portraiture to create a canvas of spiritual intensity and chromatic resonance. Through simplified form, radical color contrasts, and painterly immediacy, he transforms an anonymous sitter into an emblem of universal humanity. This analysis has traced the painting’s context within early Expressionism, examined its compositional rigor, unpacked the symbolic use of color and light, and reflected on its emotional power. Ultimately, “Egyptian Girl” endures as a testament to art’s ability to convey not only outer likeness but the inner light of the soul—making it a lasting icon of modernist exploration