Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

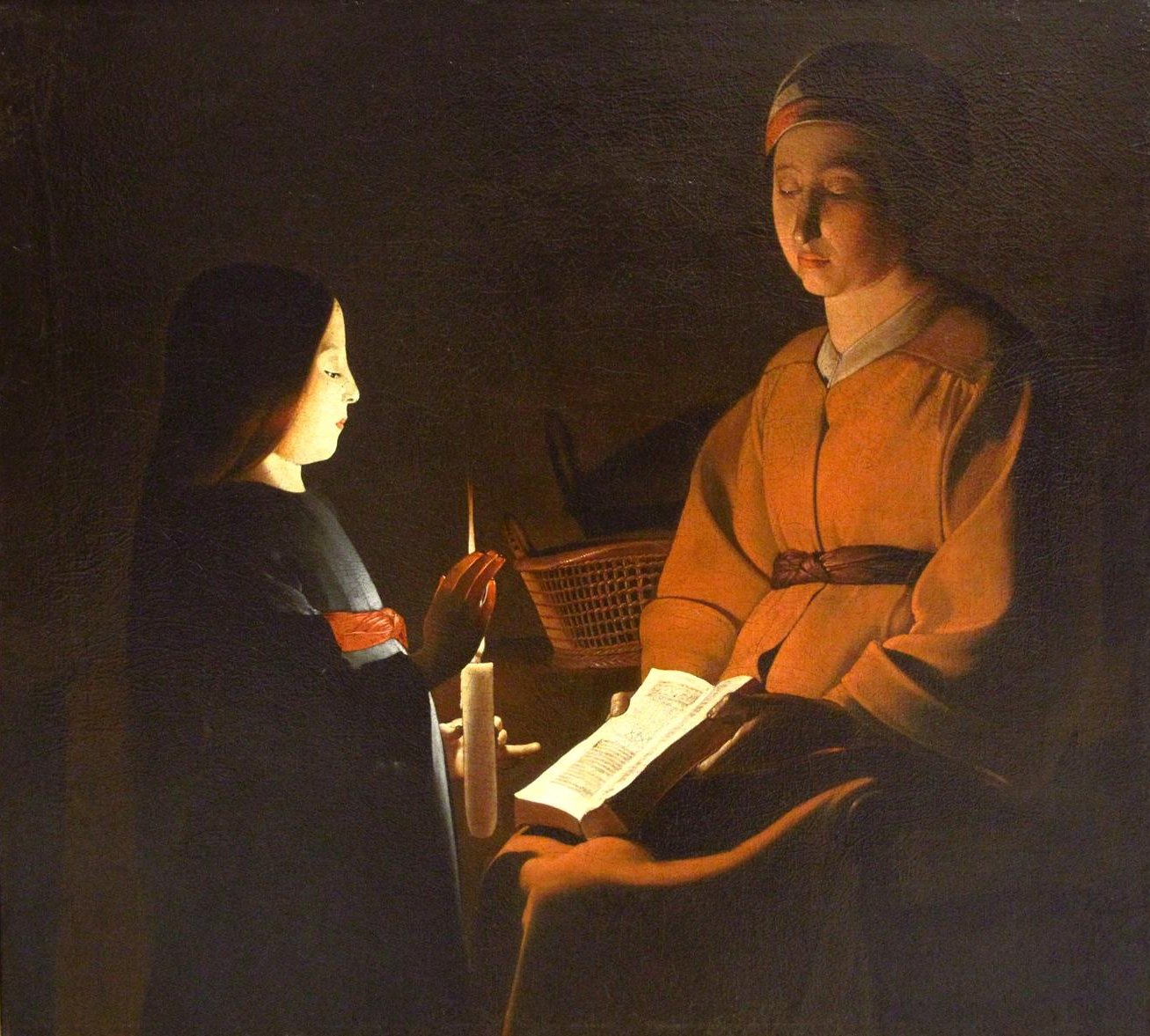

Georges de la Tour’s “Education of the Virgin” (1640) captures an intimate lesson shared between mother and child and turns it into a meditation on light, language, and the slow work of formation. In a bare interior, Saint Anne sits with a book open across her knees while the young Mary stands beside a single candle, her hand raised to shield the flame and direct it toward the page. The room is humble—a woven basket in shadow, simple garments, no ornament—yet the scene feels monumental because de la Tour treats the exchange of words and light as sacred labor. Nothing interrupts the flow between the flame, the page, and two faces shaped by attention. The painting belongs to the artist’s late nocturnes, where one source of illumination carves a whole world from darkness and establishes an ethics of looking rooted in calm and clarity.

Composition and the Geometry of Learning

The composition is an elegant dialogue of vertical and horizontal forms. Saint Anne’s seated body builds a stable triangle at the right of the canvas: her torso forms the upright side; the draped knees create the base; the downward line of her bowed head completes the shape. Mary’s slender figure anchors the left side with a vertical column that parallels the candle. Between them, the open book crosses Anne’s lap like a bright bridge. The triangle and the column meet at the page, where light gathers and meaning begins. De la Tour suppresses extraneous diagonals; even the basket in the background is angled just enough to echo the page without competing with it. By simplifying architecture into a few large shapes, the painter gives the eye a measured path—child, flame, page, mother, and back again—so the act of looking imitates the act of teaching.

Light as the First Teacher

A single candle governs the scene, and de la Tour paints it like a patient pedagogue. Its flame is thin and upright; its halo is modest; its power is focused. The light strikes Mary’s cheek first, establishing the primacy of the learner. It then passes through her uplifted hand, which both shields and channels the glow, and lands on the page in a clear wedge. Only after the page is legible does the light move to Saint Anne’s face and sleeves. This sequence—child, page, mother—is the painting’s thesis about instruction: the learner’s face must be illuminated, the text must be made visible, and the teacher must take her place within that same light. Darkness is not menace here; it is the respectful reserve that allows illumination to have meaningful borders.

Chiaroscuro Without Spectacle

The nocturne’s drama is quiet. Unlike the fractured highlights of more theatrical Baroque canvases, de la Tour uses large, even planes to model form. The shadow around Mary is deep but gentle; the transition across her cheek is a long gradient; the highlight on her small hand is crisp but not flashy. Saint Anne’s garment reads as a set of warm, breathing volumes rather than a stage costume. The open book is a bright rectangle whose pages cockle slightly, catching light along the central gutter and the lower edge. Every area of light is earned by the object’s function: flesh glows where attention is active, paper gleams where words are to be read, woven fiber dims where it can rest.

Gestures That Speak in Low Voices

The painting’s rhetoric resides in the smallest movements. Mary’s raised hand, fingers slightly parted, forms a living lampshade—an act of care that also implies agency in her own learning. She is not a passive recipient; she helps make the page readable. Saint Anne’s hands cradle the book with long practice, thumbs set as bookmarks, wrists relaxed but steady. Her head inclines, eyes soft shut or nearly closed, as if reciting from memory while letting the child follow the lines. De la Tour never forces gesture; he trusts practical actions to generate meaning. The mother’s sheltering steadiness and the daughter’s cooperative attention create the grammar of education without a single theatrical flourish.

The Book as Bridge Between Two Worlds

Few artists give the book such persuasive weight. The folio across Anne’s knees is thick, its pages edged with shadows that prove their substance. It is not a symbol floating in allegory; it is an object whose paper must be turned, whose margins invite a finger to guide a child’s eye. Because the book’s light is shared by both readers, it functions as a bridge: meaning passes through words into bodies and back again. In a sacred context, this is Scripture forming the one who will one day consent to its fulfillment. On a human level, it is simply the power of text to knit attention across generations.

Color Harmony and Emotional Temperature

De la Tour restrains his palette to a chord of warmed ochres, umbers, earthen oranges, and deep browns, tuned by the candle’s pale lemon. Mary’s dark dress carries a narrow ribbon of red at the sleeve, a single accent that echoes the warmer notes of Anne’s robe. Skin tones are ivory warmed by reflected light from the page. Because chroma is quiet, temperature carries emotion: the room feels humanly warm without sliding into sentimentality. No extraneous color distracts from the conversation of flesh, flame, and paper. The mood is the thermal equivalent of a hearth with the world fallen away beyond the door.

Texture and the Truth of Simple Things

Material truth is one source of the painting’s credibility. The basket’s weave recedes into brown shadow yet retains enough texture to read as a useful domestic object. Anne’s robe is mapped with soft highlights that catch on the seam and belt, proof of a fabric thick enough to keep night’s chill at bay. The book’s paper is slightly cockled, the way a well-used page warps under the warmth of hands. The candle is a simple tallow stick, its surface beginning to crater near the wick. None of these details call attention to themselves; they simply keep the world true so that the moral can rest on trustworthy things.

Space, Silence, and the Room Where Words Become Flesh

The background is recessive and undefended—no window, no arch, no stage furniture. De la Tour treats space as silence, a hush that thickens around the figures so their exchange can be heard. That silence has a theology: the Word grows in rooms like this, not in spectacle. The blank wall receives, very softly, the candle’s reflected glow, turning emptiness into a collaborator. The painting suggests that education is an architecture of quiet as much as a project of content.

Faces and the Psychology of Formation

Mary’s face is turned fully to the light, its planes simplified so that the transition from bright cheek to shadowed hair reads as one resolute decision. She is “facing” illumination literally and figuratively. Saint Anne’s features are fuller, modeled by experience; her downcast eyes register both concentration and the humility of a teacher who knows her task is to deliver understanding, not to display it. The two faces never meet; their connection is triangulated through the page. Eye contact is replaced by shared attention, a psychological truth any teacher will recognize.

The Candle as Metaphor of Time and Care

In de la Tour, light is never just physics. The candle is an hourglass of flame, measuring the lesson’s dwindling minutes. Its tidy wick and upright tongue of fire also record care: someone trimmed it before the reading began. Mary’s raised hand tunes that flame in real time, preventing glare, making the page legible without smoke or sputter. Learning happens inside such maintenance. The painting honors the mundane stewardship—fuel, trimming, shielding—by which knowledge is transmitted across dusk.

Dialogue with De la Tour’s Other Nocturnes

De la Tour’s late style returns repeatedly to domestic night—Magdalenes contemplating skulls, saints reading letters, mothers tending infants. “Education of the Virgin” stands out for its double portrait of attention. Where the Magdalenes stage interior conversion and the Jeromes record solitary study, this canvas celebrates attention made social. The mother’s steadiness and the daughter’s eagerness exist in the same light, as if the artist wished to demonstrate that contemplation and instruction share a single atmosphere. The basket in shadow rhymes with the cradles in his Nativity scenes, linking study to maternity: both are forms of sheltering growth.

Symbolism Grounded in Use

Iconography is present but modest. The book is Scripture; the candle is divine illumination; the basket hints at the chores waiting beyond the lesson; the red ribbon on Mary’s sleeve can be read as a thread of future passion woven into childhood. Yet each symbol is kept practical. The book must be held; the candle must be shielded; the basket must be carried; a ribbon keeps a sleeve from falling into wax. The painter refuses to detach meaning from function. It is precisely this grounded symbolism that gives the picture its persuasive power.

Technique, Edge, and Plane as Persuasion

De la Tour’s method favors big planes and a few decisive edges. The fold where Anne’s robe closes at the sternum is a single, clean line that makes the garment credible and centers the torso. The rim of the book receives a precise highlight, after which the pages soften into the middle tones that carry text. Mary’s hand against the flame has just enough crispness to separate fingers from halo; elsewhere, the contour of her hair dissolves gently into darkness. Brushwork hides; glazes warm skin; scumbles on the wall catch a breath of light. Nothing is fussy. The technique is a moral stance: let the subject be seen without interference.

The Ethics of Looking and the Viewer’s Position

We stand just outside the circle of illumination, close enough to feel the lamp’s heat, far enough to keep from startling the child. Neither figure looks at us. Our role is to witness fairly, to let our gaze mirror the steadiness of theirs. The painting disciplines the viewer’s sight, asking for patience and modesty. Even the temptation to identify or sentimentalize is gently checked by the room’s sobriety. What matters is not how adorable the child is or how pious the mother appears, but how light and words build a life together.

Color as Quiet Music

Though the palette is restrained, color plays a subtle music across the surface. The orange-brown of Anne’s robe deepens toward the waist, relieved by the softer beige of collar and cuff; the red ribbon on Mary’s sleeve strikes a single warm note that echoes faintly in the basket’s interior and the flame’s core. The black of Mary’s dress is actually a deep blue-brown that accepts the candle’s warm kiss along its cuff. These modulations keep the eye alert inside the hush. Color here is not decoration; it is tempo.

The Humanism of Domestic Learning

The painting’s enduring appeal lies in its human scale. De la Tour honors a routine moment—the end of the day, a page read aloud, a child standing at the candle—with the gravity usually reserved for altarpieces. He suggests that the divine strand of Mary’s story is braided through ordinary discipline: someone taught her letters, someone lit the light, someone kept a book in the house, someone loved her enough to give the evening to words. The picture transposes theological grandeur into the key of habit, and in doing so it enlarges our sense of where meaning takes root.

Time’s Breath and the Rhythm of the Page

The scene holds a specific, unrepeatable minute. Wax gathers at the candle’s lip; a small tail of smoke is absent, implying still air; Anne’s thumb sits between pages, ready to turn; Mary’s hand has not yet lowered from the shielding pose. The breath of time is suspended for us—no drama, only the rhythm by which another line will soon be sounded and the light will continue its patient work. De la Tour is the painter of that rhythm, which is how the painting continues to feel modern: it venerates the minutes in which lives are actually formed.

Modern Resonance and the Grace of Attention

Strip the figures of their period clothing and the tableau remains instantly recognizable: a caregiver and child reading by a small light at day’s end. In an era of screens and fractured focus, the image proposes a counter-liturgy of attention. Shield the flame, center the page, share the beam, let two faces be shaped by the same light. The painting does not scold; it invites. Its quietness proves that the most radical practice may simply be to sit together and read.

Conclusion

“Education of the Virgin” is de la Tour’s hymn to the ordinary sacrament of learning. With a single candle, an open book, a basket in shadow, and two concentrated faces, he composes an ethics of illumination: light must be tended; words must be honored; rooms must be made quiet; hands must cooperate; time must be spent. The composition’s geometry guides the eye into a loop of attention; the light’s sequence teaches priorities; the color’s warmth sustains intimacy; the textures’ truth secures belief; the gestures’ modesty protects the scene from sentimentality. Nothing is superfluous. Everything is necessary. In that necessity, the painting finds grandeur: a child being taught to read by lamplight in a small room becomes an image of how the world is kept alive, one page, one breath, one lesson at a time.