Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

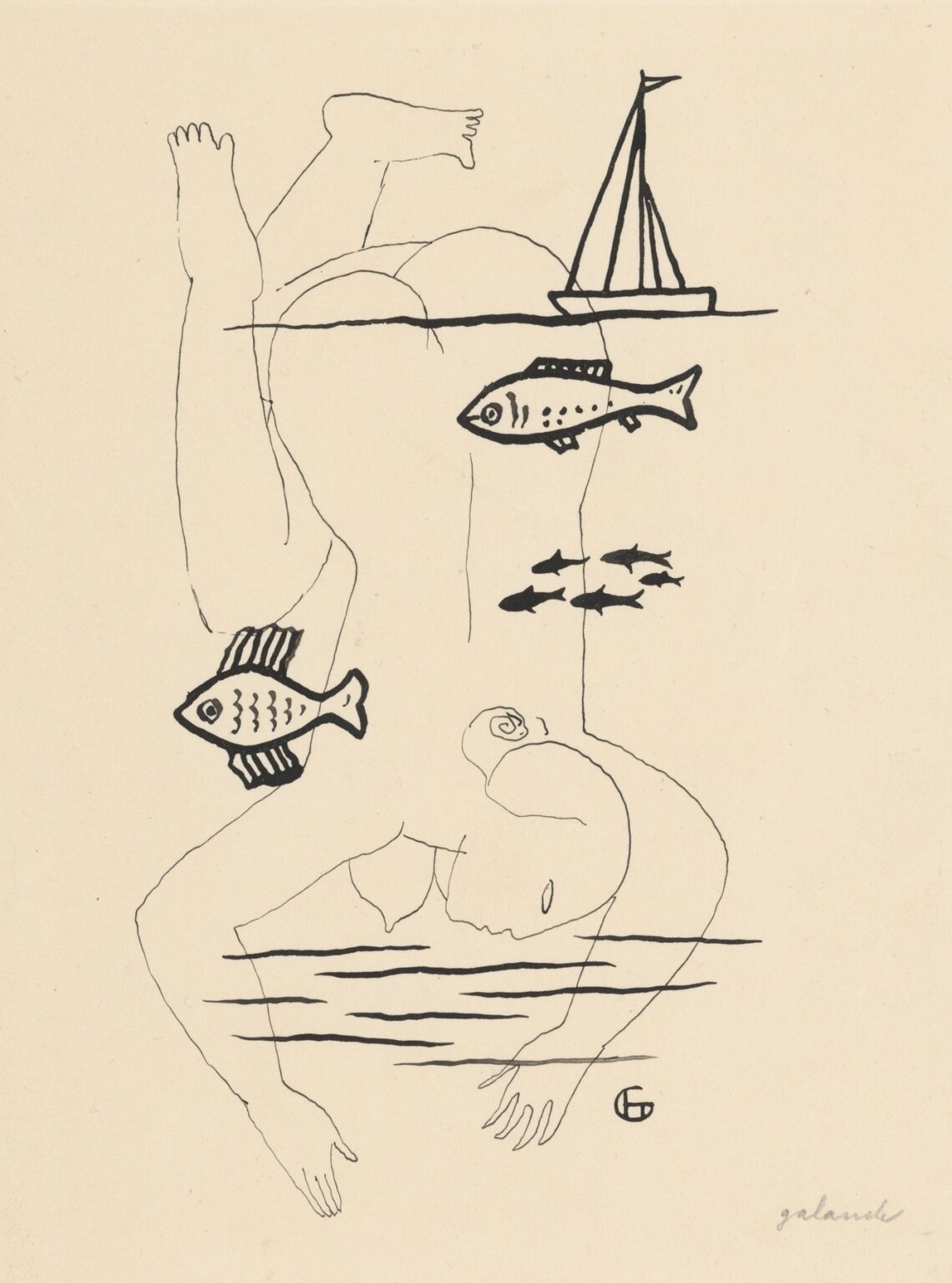

Mikuláš Galanda’s Drowned (1930) confronts viewers with a deceptively simple arrangement of line and symbol that belies its profound meditation on mortality, isolation, and the fragile boundary between life and death. Rendered in pen and ink on a cream‑toned paper ground, the drawing portrays a solitary human figure partially submerged, inverted, and entangled with aquatic motifs: fish of various sizes and a small sailboat floating on the horizon line. Galanda’s characteristic economy of line—his ability to suggest flesh, water, and movement with a few confident strokes—imbues the composition with an eerie stillness that resonates long after one’s gaze has shifted away. Through Drowned, the artist channels both the universal fear of being overwhelmed by forces beyond control and the somber beauty that can emerge when form is distilled to its essentials.

Historical Context

Created in 1930, Drowned emerges against the backdrop of Europe’s interwar period, a time marked by political upheaval, lingering trauma from World War I, and the global economic turmoil of the Great Depression. Czechoslovakia, established in 1918, was navigating its national identity while fostering a vibrant avant‑garde scene. Slovak artists like Galanda sought to modernize their country’s visual language by integrating elements of Cubism, Fauvism, and Expressionism, yet always infusing their work with local cultural resonances. The theme of drowning—both literal and metaphorical—would have evoked anxieties about rapid social changes, the precariousness of individual agency, and the specter of geopolitical forces sweeping ordinary lives under. Galanda’s drawing can thus be seen as both a personal reflection and a resonant allegory for the collective uncertainties of his era.

Galanda’s Artistic Evolution

Mikuláš Galanda (1895–1939) charted a course from vibrant color experiments in the early 1920s through a gradual refinement of line and form in his later graphic works. After absorbing Fauvist colorism and Cubist deconstruction during his studies in Budapest and Prague, Galanda began to distill his visual vocabulary into monochrome drawings and prints. By the late 1920s, he had embraced an economy of means—favoring pen, ink, and occasional collage over paint—so as to emphasize the expressive potential of contour and negative space. Drowned stands at the apex of this trajectory: it eliminates all superfluous detail, relying instead on the interplay between drawn figure, aquatic symbols, and the untouched paper ground to evoke a powerful emotional response.

Compositional Structure

Dark, horizontal lines cut across the upper and lower thirds of Drowned, establishing the surface and depths of the water. The human figure, rendered with a single, continuous contour in places, appears inverted: the head and outstretched arms lie beneath the lower horizon, while the legs and feet breach the upper boundary. This inversion creates a sense of disorientation and underlines the figure’s loss of agency—submerged yet visible, immobile yet suspended in a moment of liminal stasis. Two fish—one large, one a shoal of smaller fish—swim amidst the limbs, their more detailed forms contrasting with the figure’s transparent outline. A small sailboat drifts on the surface above, appearing almost carefree, its minimal mast and hull suggesting human enterprise untroubled by the tragedy below. Through this arrangement, Galanda orchestrates a silent drama of tensions: above/below, life/death, freedom/entrapment.

The Power of Line

Galanda’s penwork in Drowned is both spare and eloquent. The figure’s outline varies from thin, tentative strokes around the torso to slightly heavier lines along the arms and legs, conveying subtle shifts in emphasis and suggesting a three‑dimensional presence despite the flat paper. The water lines are drawn with bold certainty, their straight segments contrasting with the softer curves of flesh. Fish are depicted with concise, gestural marks: a few hatch strokes indicate scales, a single curve defines the fin. These deliberate variations in line weight and style produce a dynamic interplay between figure and symbol, surface and depth. Each stroke carries the weight of emotional intention, channeling Galanda’s modernist conviction that line alone can convey the full spectrum of human feeling.

Spatial Ambiguity and Psychological Depth

By forgoing any background detail beyond horizontal lines for water, Drowned plunges viewers into a psychologically charged no‑man’s land. There is no horizon other than the two waterlines; there is no shore, sky, or contextual setting to anchor the drawing in a specific place or time. This spatial ambiguity intensifies the work’s existential tenor: the submerged figure becomes everyman and no‑one simultaneously, caught in an abstract realm where the familiar laws of gravity and orientation cease to apply. The inverted posture heightens the disquiet—a gesture of helpless surrender rather than active struggle. Galanda thus transforms water, a symbol of life and movement, into a silent agent of stasis and reflection, inviting viewers to project their own fears and yearnings onto the ambiguous scene.

Symbolism of Drowning

Drowning has long served as a potent symbol in art and literature, representing not only physical peril but also emotional engulfment and the dissolution of self. In Drowned, the motif of submersion captures multiple layers of meaning. The figure’s transparency suggests a loss of identity, as if the body is dissolving into water. The fish, agents of underwater life, circle around the limbs with uncanny detachment, perhaps implying that nature continues its indifferent rhythms even as humans suffer. The small sailboat on the surface stands as an emblem of human aspiration and progress but also as a stark reminder of the gulf between safety above and peril below. Through these juxtapositions, Galanda explores the precarious balance between mastery and vulnerability, inviting contemplation of how easily one can slip beneath life’s surface into the unknown.

The Human Figure: Form and Gesture

Although stripped to a bare outline, the drawing of the human form in Drowned is unexpectedly precise in its proportions and gestures. The arms extend sideways with subtle curvature, the hands articulated with minimal but convincing marks for fingers. The torso’s gentle bulge and the rounded shape of the hips introduce a softness that contrasts with the sharp waterline. The legs, bent at the knees, break the upper horizon as if seeking air or relief. This posture conveys both resignation and an unconscious attempt at self‑rescue. By avoiding facial detail entirely, Galanda universalizes the figure—erasing individual features to symbolize any person’s plight. The viewer is thus drawn into an empathetic space where the specifics of identity fade, leaving only the raw essence of human struggle.

Fish and Boat Motifs

The maritime symbols in Drowned—fish and sailboat—serve as narrative anchors in an otherwise abstract composition. The two fish, individually rendered with patterning and hatchwork, appear lifelike and poised, as though investigating the intruder in their domain. Meanwhile, a small shoal of five fish, depicted as simple silhouettes, swims in formation near the figure’s midsection, introducing a rhythmic repetition that echoes school behavior. Above them, the sailboat’s straight mast and triangular sail suggest human ingenuity and the promise of journey. Yet its diminutive scale and casual drift imply potential abandonment or obliviousness to the struggle beneath. These symbols together articulate the teetering boundary between human intervention and nature’s relentless cycles, underscoring the vulnerability inherent in any voyage—whether across oceans or through life’s deeper currents.

Technical Mastery and Medium

Galanda’s choice of pen and ink on paper allowed for immediate, direct expression and precise control of line. The ink’s depth varies depending on pen pressure and drawing speed, with thicker lines for horizons and key contours, and wispy strokes for hatchwork and textural accents. The cream‑toned paper, speckled with natural fibers, contributes warmth and subtle texture, preventing the drawing from feeling coldly schematic. Close inspection reveals micro‑variations: tiny ink splatters in the fish’s scales, slight hesitations in the waterline, and gentle feathering at the tips of submerged limbs. These traces of hand and material fidelity reinforce the work’s emotional resonance, reminding viewers that beneath the abstracted forms lies an artist’s lived gesture.

Emotional Resonance and Viewer Engagement

Drowned exerts a compelling emotional pull through its stark contrasts and haunting imagery. The inverted figure—neither fully alive nor clearly dead—elicits empathy and unease. Viewers find themselves asking fundamental questions: Is the person unconscious or at peace? Will the sailboat notice and offer rescue? Are the fish companions or indifferent bystanders? This narrative openness invites prolonged engagement, as one’s gaze moves between contours, symbols, and negative space. The drawing’s emotional power resides not in dramatic detail but in its capacity to evoke universal feelings of helplessness, uncertainty, and the thin membrane separating survival from surrender.

Legacy and Significance

Though Mikuláš Galanda’s life ended prematurely in 1939, Drowned remains one of his most evocative and widely studied works. It exemplifies his mature synthesis of modernist abstraction and humanist empathy, anchoring Slovak avant‑garde art within broader European currents while retaining a distinct regional voice. In subsequent decades, the drawing influenced generations of Czechoslovak graphic artists, who looked to its fusion of poetic symbol and formal clarity as a model for exploring complex social and psychological themes. Today, Drowned continues to resonate in exhibitions and scholarship, serving as both a testament to Galanda’s visionary artistry and a timeless meditation on the human condition.

Conclusion

In Drowned (1930), Mikuláš Galanda demonstrates the transformative power of minimal means to express profound human truths. Through a careful orchestration of inverted figure, aquatic symbols, and negative space, he invites viewers into a liminal realm where the boundaries between life and death, hope and despair, safety and peril blur. His masterful line work, judicious use of symbolic motifs, and strategic abstraction create a drawing that is at once deeply personal and universally resonant. By distilling form to its essentials, Galanda crafts a visual poem on the theme of submersion—an elegy for vulnerability and a testament to the enduring capacity of art to articulate what lies beneath the surface of human experience.