Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

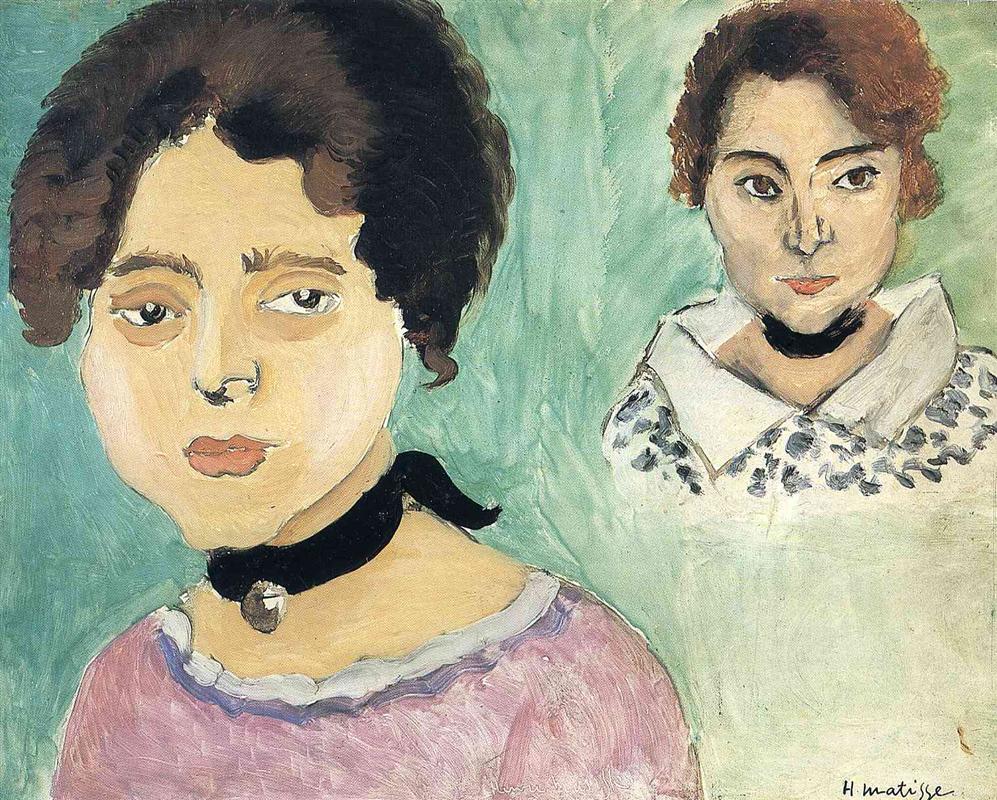

Henri Matisse’s “Double Portrait of Marguerite on Green Background” (1919) is a rare and revealing experiment in repetition. Instead of settling on a single likeness, Matisse presents two images of the same sitter—his daughter, Marguerite—floating on a continuous green field. On the left, a large, close-up head and shoulders fill the surface with a soft purple dress and a black ribbon at the neck. On the right, a smaller bust in a white-collared blouse faces forward with a steadier gaze. The two images share the same space yet do not overlap; they read like adjacent thoughts held at once. With minimal props and an economy of marks, Matisse opens a window onto the way a painter shapes presence through scale, color, and the living contour of line.

The Postwar Nice Period and the Return to Clarity

Painted during Matisse’s first Nice seasons after World War I, the work belongs to a crucial pivot in his career. In Nice he cultivated a new ethic of calm, building pictures from large planes of color, steady light, and patterned structure rather than from analytical fragmentation or brutal contrast. Interiors, screens, shutters, and balcony balustrades became instruments for measuring light. Portraits, too, were rethought. Instead of psychological modeling, Matisse sought clarity of placement and harmony of temperature. “Double Portrait of Marguerite on Green Background” belongs to this program, but it adds a twist: by placing two variations of the sitter in one frame, he lets us see the mind of the painting at work.

First Impressions: Two Likenesses, One Atmosphere

The first impression is spatial and chromatic. A mint-green ground occupies the entire surface, lightly variegated with visible brushwork so that it breathes. On this field, two figures float without cast shadows. The left image dominates by scale: Marguerite’s face fills the vertical, her hair mass dark and soft, her eyelids heavy, her lips a quiet rose. A black ribbon choker ties under her chin, and a lavender-pink dress with a frill at the collar rounds the shoulders. The right image is smaller and set higher. Here Marguerite wears a white collar over a patterned blouse; her features are more sharply drawn, her eyes more alert, her mouth closed in a slight, poised line. The two heads form a diagonal dialogue across the green space, linked by the repetition of the black ribbon at the neck and by the continuity of light.

Composition as a Conversation

The composition operates like a duet. The large head on the left anchors the painting’s mass—the bass note—while the smaller bust at right provides a treble echo. Their separation leaves a wedge of green between them, a pause or breath that allows each to speak distinctly. The figure at left faces slightly to the viewer’s right, the one at right faces forward but glances to the left; in this way their gazes cross the intervening space without meeting. The devices are simple but exact: two ovals, two necks, two tonal clusters of hair and ribbon. The duplication invites the eye to compare, and comparison becomes the painting’s engine.

The Green Field as Active Space

Matisse’s grounds are never neutral. Here the green is not a backdrop but an atmosphere—pale enough to illuminate skin, cool enough to stabilize the warm notes of lips and dress, lively enough in brushwork to avoid the deadness of a flat fill. Small fluctuations in tone keep it fluttering like light on a painted wall. Because both portraits share this field, they appear to occupy the same room and moment even as they represent different takes. The color also serves a structural role: green sits between the purple of the dress and the warm ochres of skin, acting as a hinge that makes both families resonate.

Color Architecture and Temperature

The painting rests on three families of color. Cool greens and blue-greens dominate the air; warm skin tones—ochre, pink, and a touch of sienna—shape the faces; a third family of violets and soft mauves establishes clothing and shadows. A handful of blacks and near-blacks—ribbons, hair accents, pupils—provide punctuation and gravity. Matisse places these families with deliberation. The left portrait concentrates violets in the dress, pulling warmth down and letting the face’s pale ochres glow. The right portrait replaces violet fabric with a crisp white collar, so the warmth rises toward the features. Because the same black ribbon ties both necks, the two readings lock together. The harmony is temperature-driven rather than hue-noisy; nothing clashes, but small differences carry meaning.

Drawing: The Living Contour

Line in this picture is a living edge, not an outline filled in afterward. Around the larger head it swells and thins: the cheek’s border is soft, the jaw firmer; hair dissolves into the ground in feathery arcs; the choker is a thick, flat stroke that holds the head like a pedestal. In the smaller portrait the drawing is brisker, with a few decisive marks setting the nose and jaw. The eyes in both heads are reduced to essential structures—lids, pupils, small glints—yet they carry presence. Matisse’s contour does double duty. It keeps the forms on the surface so the painting remains an object, and it guides the eye from feature to feature with a rhythm that substitutes for descriptive modeling.

Brushwork and Surface

The surface is frank; you can see how the picture was made. In the green field, long strokes lay down the climate. In faces, broader patches of semi-opaque paint are left slightly open at the edges so that light seems to circulate. The violet dress is more thinly brushed, with chalky whites blooming through to suggest cloth texture. The patterned blouse at right is shorthand—flecks and small dabs indicate print without counting motifs. This variety of handling keeps each zone calibrated: air with air’s softness, fabric with fabric’s hush, features with crispness where needed.

The Psychology of Two

Why two portraits? One answer is practical. Matisse frequently returned to a motif within the same session, trying different scalings and placements to test the color chord. The second answer is poetic. Painted side by side, the two images stage the variability of a person seen over time—the same sitter, the same room, but a different measure of attention, a slightly altered mood. The larger likeness feels inward and tender; the smaller is more watchful and formed. Together they refuse the fiction that a portrait must compress a person into one fixed expression. Presence, Matisse suggests, is plural.

The Role of the Black Ribbon

The black ribbon is a small but decisive device. It anchors the head to the body, adds a horizontal band that steadies the verticals of neck and face, and provides the darkest value in the picture. Its repeat across both figures knits the diptych into a single chord. Visually it functions like the bass line in music: everything else can float because the ribbon holds pitch. Psychologically it also sharpens the fragile light of the skin; the faces feel illuminated because the ribbon gathers shadow at the throat.

Marguerite as Muse and Measure

Although Matisse resists biography in paint, Marguerite appears throughout his career as a preferred sitter because she allowed him to explore the limits of simplification. He could spare detail without losing likeness, edit garments to planes, and treat features as relational rather than anatomical facts. In this canvas, Marguerite becomes the measure by which a green air and a violet tint are calibrated. Her face is not a story but a tuning fork; when the intervals among green, violet, ochre, and black sound right, the portrait breathes.

Scale and Intimacy

Scale shifts create intimacy in two different ways. The larger head invites proximity. Its parts—eyelids, lips, curls—edge close to the viewer, and the cropped shoulders make us feel as if we are seated just in front of the sitter. The smaller bust introduces social distance; its crisp collar and patterned blouse imply a bit more formality. This play with distance is quietly theatrical. The left image is the whisper, the right image the spoken line across a room. The green field holds both voices in balance.

Space Without Perspective

There is almost no perspectival construction in the conventional sense. Space is created by overlap—the left shoulder slightly behind the face, the dress slipping under the choker, the right collar over the blouse—and by the breathing ground around forms. Because the background never breaks into architectural planes, the portraits feel suspended, as if in a studio air that has been purified of extras. That suspension is an ethical choice: it keeps the painting focused on the elemental problems of color and contour rather than on the anecdote of setting.

Rhythm and the Eye’s Path

The painting teaches a gentle loop. Many viewers begin with the larger head—its eyes, mouth, and ribbon—then slide along the shoulder’s curve into the violet dress, move across the green gap to the white collar, climb to the smaller head, and return via the ribbon’s black to the first face. Each lap strengthens correspondences: ribbon to ribbon, lip pink to lip pink, hair mass to hair mass, green halo to green halo. The pleasure comes from recognition not of likeness to a life outside the painting, but of rhymes within the painting itself.

Light and the Mediterranean Climate

The Nice climate enters not as a sunbeam but as clarity. The faces turn with almost no cast shadows; volume is declared by small temperature shifts—the cooler forehead, the warmer cheek, the green-reflective edge of jaw. The green field bathes everything in a coastal freshness that keeps the violets from congealing into heaviness and prevents the skin from becoming chalk. The light is a condition rather than a dramatic event, and that condition is crucial to the calm the painting exudes.

The Ethics of Economy

Few modern artists demonstrate more convincingly how little a painting needs to feel complete. In this work, a handful of marks defines each feature; clothing is characterized with abbreviated strokes; background is a single color allowed to vary slightly. Yet nothing feels thin. The economy stems from the firmness of Matisse’s decisions. Every stroke is placed to articulate structure, and each color carries relational weight. The result is not austerity but generosity: the viewer is invited to complete the picture with their own attention.

Kinship with Other Works of 1919

The double image converses with the single-figure portraits of the same year—women in oriental dress, women at tables, women by windows—where a shallow space, a calm light, and a patterned support prevail. Compared with those canvases, this one is freer and more experimental, sacrificing interior décor to concentrate on the face. It also resonates with the artist-and-model pictures of 1919, which think about making as part of the subject. By holding two solutions in one frame, the painting becomes a self-reflective object, presenting process as poise.

Likely Palette and Handling Choices

The concise palette suggests a practical studio setup. Lead white forms the basis of skin, dress frills, and collar. Yellow ochre and light earths warm the flesh; a touch of vermilion or alizarin cools or heats the lips and cheeks. The green background likely combines viridian or cobalt green with white and a breath of blue to keep it Mediterranean rather than acidic. Violet-lavender in the dress arises from a red lake tempered with ultramarine and white. Ivory black clarifies pupils, ribbons, and a few structural contours. Paint is mostly opaque, with translucent scumbles along cheeks and blouse to allow the ground to participate.

How to Look

Stand close first. Notice how the left eyelid is a single curved stroke, how the choker’s knot is suggested rather than described, how the blouse’s print on the right emerges from quick, confident dabs. Step back and watch the two heads shift scale relations: the larger grows tender, the smaller grows articulate. Focus on the green between them—it is not empty but quietly active. Then let your gaze circulate ribbon to ribbon, mouth to mouth, eye to eye, until the difference between the two becomes a kind of visual music.

Meaning Without Anecdote

The work refuses anecdotal drama. It does not tell you what Marguerite was thinking on that day or what occurred before or after the sitting. Its meaning arises from the felt experience of variation within sameness. To see two portraits of one person is to recognize that identity in painting is not a photograph but a relationship among colors and edges at a given moment. By holding both options, the canvas invites a viewer’s freedom: you can prefer one or allow them to coexist, as moods do in a quiet afternoon.

Conclusion

“Double Portrait of Marguerite on Green Background” is a compact manifesto for Matisse’s Nice period. With a green atmosphere, a violet dress, a white collar, and two pairs of dark eyes tied by two black ribbons, he constructs a scene that is both intimate and analytical. The doubled likeness acknowledges that a single image cannot exhaust a face, and the calm air affirms that painting can be a space where differences sit together without conflict. The work remains fresh because it shows painting thinking—choosing, comparing, and placing—until presence appears.