Image source: wikiart.org

A Young Master’s Measure of Authority

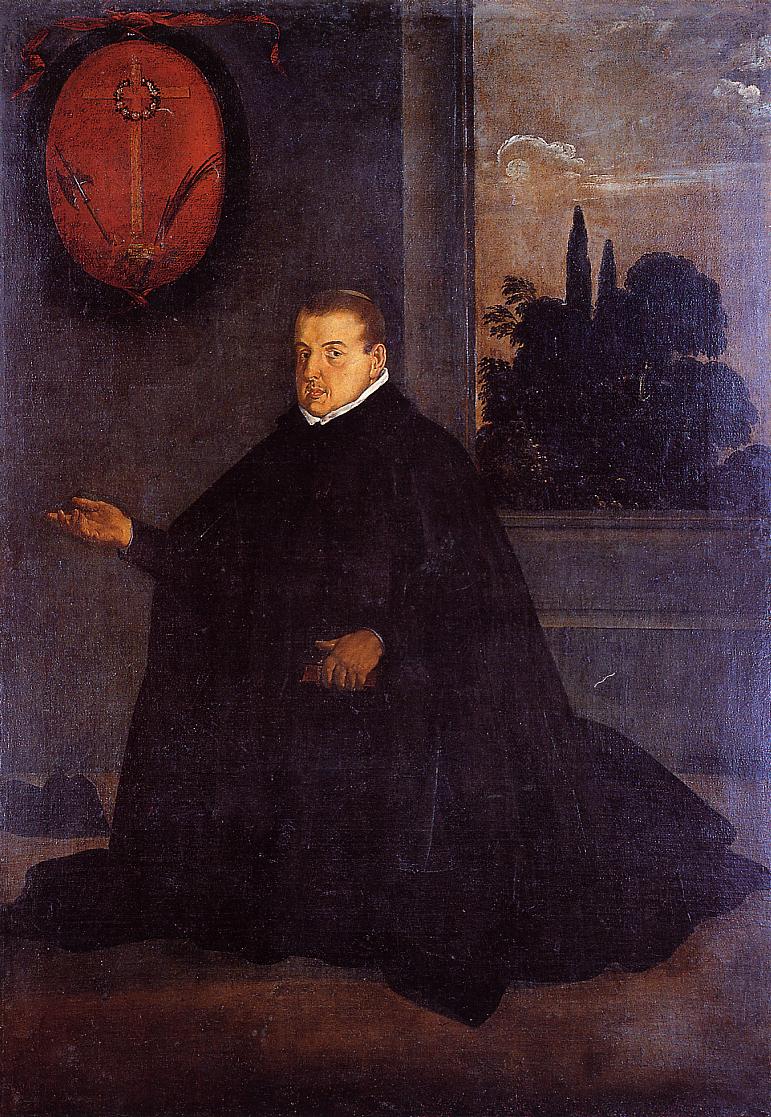

Diego Velázquez’s portrait of Don Cristóbal Suárez de Ribera distills power without spectacle. The sitter, wrapped in a dark clerical mantle, occupies a sober interior punctuated by two visual anchors: an oval red escutcheon on the wall and a window that opens onto cypress and cloud. Nothing clamors for attention—no silver, no brocade, no parade of props. Instead, the picture builds authority from stance, light, and the quiet rhetoric of hands. The result is a likeness that feels judicial and pastoral at once, a public figure presented with the intimacy of a private audience.

A Composition That Grounds and Guides

Velázquez organizes the canvas as a conversation between verticals and broad, stabilizing masses. Don Cristóbal’s body forms the dominant dark triangle that settles the lower half of the picture like a foundation stone. His head—small in relation to the enveloping garment—rises into a band of lighter wall, so the face becomes the only bright, warm shape in a field of cool grays and blacks. At the upper left, the red shield lifts the key note of color; at the right, the window’s rectangle admits a cooler light. These two high accents balance the sitter as if he were bracketed by emblem and landscape, duty and world.

The arms supply the linear drama. One hand extends, palm up—an eloquent gesture of address or instruction—while the other secures a small book. Those diagonals subtly aim the viewer’s eye toward the head, so the portrait reads in a clear sequence: gesture, mind, seal of office, horizon.

The Face as the Room’s Light

Velázquez makes the head the canvas’s lamp. Light falls soft and frontal, coaching the forehead, cheek, and nose into legible planes while sparing the eyes enough shadow to keep thought alive. The modeling is economical but exact: a crease gathering beside the nostril; a cool halftone under the brow; the tender, rounded triangles at the corners of the mouth. The sitter’s gaze is not theatrical. He looks slightly past us, as if listening for the next sentence of a conversation he began. In a painting largely built from dark cloth and stone walls, this tempered warmth turns the face into the image’s moral weather.

Black That Isn’t Empty

The enormous field of black is where Velázquez’s early discipline shows most clearly. The mantle is not a hole in the image; it is a world of values. Wide slopes catch a muted gleam; seams establish gentle ridges; the hem sinks into brownish shadow near the floor. The painter orchestrates minute temperature shifts—cooler on the wall side, warmer near the hand—to prevent the dark from flattening. This is tenebrism translated into sobriety: drama is present, but the form breathes rather than shouts.

A Public Image with Private Gravity

The sitter’s dress and setting identify him as a man of the Church and of municipal standing—someone who speaks for institutions and souls. Velázquez honors both roles. The open right hand reads as a civic gesture, offering argument, welcome, or judgment; the left hand, closing around a small volume, suggests breviary or statute book, prayer or law. Held together, they tell a balanced story: a life split between contemplation and administration, scripture and ordinance, conscience and city.

The Escutcheon: Theology in Heraldry

High on the left wall hangs an oval shield the color of hot wax. Within it, a cross stands with a small wreath above—an emblem that reads like a crown of thorns—flanked by instruments that recall Passion imagery. The device functions as compressed theology and biography. It locates Don Cristóbal within a fraternity of cruciform meaning and also serves as his public seal, the mark that authenticates decrees and letters. Velázquez paints it with just enough shine to make the surface feel lacquered, but never so bright that it steals light from the face. The heraldry is acknowledged, not idolized.

The Window: A Second Kind of Authority

On the right, a window opens to a restrained landscape: cypresses rising against evening sky, a bank of trees cupped by low cloud. The view performs several tasks at once. It provides cool light that grazes the wall and rim-lights the sitter’s left sleeve; it breaks the interior’s austerity with a breath of wind; and it hints at jurisdiction—the world beyond the room that his decisions will touch. In early portraits Velázquez often uses a window as a counterweight to insistent indoor darkness; here it becomes a quiet metaphor for the outward reach of office.

Hands That Speak Before Words

Few painters match Velázquez for the expressiveness of hands. Don Cristóbal’s right hand opens in a measured arc, the thumb slightly raised, the fingers separated enough to articulate each joint. The wrist is steady, not theatrical. The left hand clamps the little book with a grip that is firm yet relaxed, the knuckles barely whitening. The language of the limbs is precise: I speak, I read; I address you, I am grounded in text. Without resorting to emblem piles, the portrait communicates vocation as fluently as any long inscription.

Light, Shadow, and the Syllabus of Character

Illumination here is a moral argument. It gives to the face and the palm a clarity that suggests candor; it leaves the mantle and the corner behind the sitter in a darker middle value that hints at the weight of responsibility. The wall adjacent to the window records a gentle falloff of light—proof that we are in a real room and not a stage set. The painter’s soft half-tones keep the transition human-scaled; nothing flips from blinding to blank. In that visual courtesy, we sense a parallel courtesy in the sitter’s manner: measured, conserving, exact.

The Palette’s Discipline

Velázquez builds the image from a short list of colors: black and brown for the habit and floor; cool grays for the wall; a restrained range of flesh tones punched with vermilion at the lips and ear; a single, commanding red for the escutcheon; and the cool green-black of cypress outdoors. Such restriction creates unity and moral tone. The red, because it is nearly the only saturated hue, reads as consecrated and institutional. The explosion of chroma you might expect in later court portraits is absent; authority here sits in value relations rather than in color display.

Texture Without Bravura

Stand close and the surface reveals a painter already confident enough to do less. The cloth is rendered with long, loaded passes that turn just at the right moment to make a fold; the face moves in soft, patient transitions, with the paint slightly thicker on the illuminated planes; the escutcheon’s rim is drawn with a single steady stroke and one or two bright beads to suggest gloss; the landscape is thin and airy, almost a wash in places, so it recedes naturally. Nothing seeks applause. Everything aims to be sufficient.

Silent Architecture

The room itself—hard to diagram, easy to believe—consists of a shallow zone of floor, a main wall, a window jamb, and a return wall that makes a crevice of darkness behind the sitter. This is minimal architecture used maximally. It anchors the figure, frames the shield, and builds a subtle perspective that nudges the eye from the open hand to the face and then out to the trees. In an early Sevillian portrait tradition that sometimes clutters, Velázquez chooses restraint. The quiet room lets institutional symbols and human presence share one air.

A Psychology of Calm Strength

What remains after the sweep of mantle and the calculus of light is the man. Don Cristóbal’s mouth holds a faint firmness; the cheeks carry a modest flush; the eyes—slightly hooded—balance intervention with forbearance. He seems to be a person whose power is procedural, not personal: influence via position and reason rather than charisma alone. Velázquez secures that reading not through narrative props but through the poise of the head and the phrasing of gesture. The sitter appears both reachable and remote, which is precisely how public trust survives.

Sevillian Realism, Institutional Portraiture

This image belongs to the world that produced Velázquez’s bodegones and early saint series: a realism disciplined by tenebrism and sensitive to the status of humble things. Transposed into institutional portraiture, the same ethic rejects parade armor and gilt; it prefers truthful planes, measured texture, and a few meaningful signs. The picture anticipates the painter’s later mastery of court likenesses, where rank is made legible through posture and air rather than through costume excess.

The Little Book and the Larger Word

The volume in the sitter’s left hand is small enough to be a pocket breviary or devotional manual, but the painter refuses to label it. That ambiguity lets the object reach beyond a single identity. The book stands for a habit of reaching for text before speech, the confidence that words tested in prayer or law can steady an outstretched hand. Velázquez gives the edges a crispness that implies use—pages slightly uneven, the cover’s corner smoothed by handling—so the symbol remains tangible.

The Coat of Arms as Acoustic

The ripe, lacquered red of the escutcheon rings like a struck note in the otherwise muted room. It sets the pitch for the portrait’s publicness. The ribbon that holds it flutters lightly, a rare ornamental curve in a painting of straight talk. Because the field is oval, it rhymes with the sitter’s face; because it is lifted high, it refuses to compete with the face’s moral priority. It is the acoustics of office rather than the melody.

The Landscape as Breath

Through the window, the line of cypress and cloud is unmistakably Mediterranean and ecclesial—cypress as a near-liturgical tree, familiar in cloister and cemetery. The cool distance gives the picture a lung. After the close argument of cloth and wall, the eye inhales space; returning to the face, we read the gesture afresh. Velázquez uses this inhale-exhale rhythm repeatedly in his early work to hold attention without fatigue.

How the Painting Teaches Us to Look

The image proposes a method of viewing: begin with the open hand (address), move to the head (mind), acknowledge the shield (office), step out the window (world), and return to the book (source). That loop recapitulates the sitter’s daily circuit. In mirroring it, Velázquez folds biography into composition. The portrait is not only a likeness; it is a diagram of a life in use.

An Early Signature of Restraint

Though painted early, the picture carries trademarks that will make Velázquez peerless: edges that carry atmosphere, brushwork trimmed to what the substance demands, faces that resist caricature, and a faith that presence can out-argue ornament. Don Cristóbal Suárez de Ribera is not flattered; he is steadied—by light, by cloth that behaves, by a room that holds, by emblems that mean because they are painted with respect.

Why This Image Still Persuades

The portrait speaks to contemporary eyes because it models a kind of power many miss: the authority of steadiness. Nothing here is algorithmic; nothing begs for applause. The sitter’s dignity rests in the quiet of his pose and the clarity of his relation to symbols and world. Velázquez’s achievement is to make that quiet visible. In doing so, he gives us a template for trust—a reminder that the weight of office is borne best when the person stands like this: grounded, attentive, and lit by a light that is bright enough for truth and soft enough for mercy.

Conclusion: Office Held in Human Scale

This painting measures public life in human units—hand, book, face—and lets heraldry and horizon serve rather than dominate. Velázquez composes with the confidence that a single, well-lit head and a disciplined field of black can say more about character than a roomful of trophies. Don Cristóbal Suárez de Ribera emerges as a man of law and liturgy whose power is the kind that lasts: the gravity of someone for whom speaking and reading are the same act of care.