Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

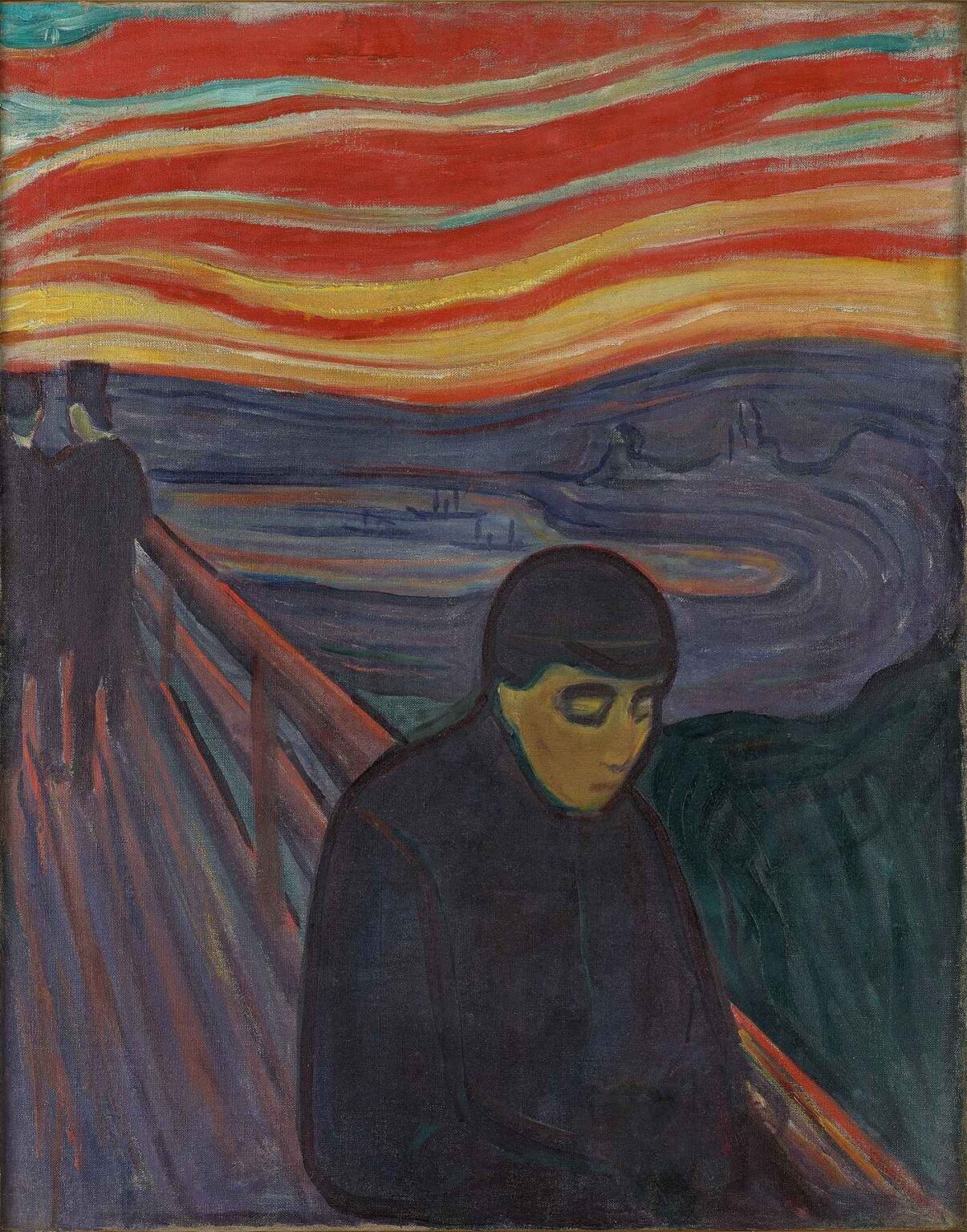

Edvard Munch’s Despair, created in 1894, stands as one of the artist’s most powerful visualizations of existential anguish. The painting depicts a solitary figure leaning heavily on a wooden railing, head bowed and hands clasped in a gesture of utter desolation. Behind him, the sky roils in bands of fiery red and molten orange above a restless, dark sea. With bold, simplified forms and a turbulent palette, Munch captures the visceral experience of inner turmoil. The work invites viewers to confront the universality of suffering, to witness the point at which emotional weight becomes almost physically unbearable. In Despair, Munch distills the human psyche into its rawest components—body, landscape, and color—demonstrating both his mastery of Symbolist expression and his pioneering role in the emergence of modern psychological portraiture.

Historical Context

By the mid-1890s, Munch had already earned a reputation for art that pierced conventional decorum. His earlier paintings—such as The Sick Child (1885–86) and The Scream (1893)—had explored themes of loss, anxiety, and isolation, often scandalizing audiences with their candor. Norway’s conservative establishment viewed his candid depiction of psychological crisis as morally suspect. Yet at the same time, Munch’s work resonated deeply with a broader European Symbolist movement, which sought to externalize inner states through evocative imagery and color. Despair emerged at a moment when Munch was refining a personal visual language: one in which the landscape becomes a reflection of the soul, and the boundaries between figure and environment dissolve. Painted just a year after The Scream, this work reveals Munch’s evolving interest in narrative more subdued yet equally intense.

Subject Matter and Iconography

At the heart of Despair lies an archetype—the isolated individual overwhelmed by forces greater than himself. The man’s bowed posture and the gesture of clasped hands pressed against his forehead suggest both physical and mental collapse. The wooden railing, rendered in stark vertical and diagonal lines, can be read as a barrier between him and an unknowable abyss. Beyond, the agitated water and the fiery sky speak in a universal pictorial language: here is grief, here is dread, here is a confrontation with nothingness. Munch refrains from including identifying details—there is no face to name, no costume to date—so that the figure’s distress becomes a symbol for any person’s moment of utter despair. The painting thus functions as an emotional parable, in which personal biography gives way to collective resonance.

Composition and Form

Munch’s compositional choices in Despair intensify the work’s psychological impact. The railing cuts diagonally across the canvas, guiding the viewer’s gaze toward the horizon. The figure occupies the lower right quadrant, his mass of dark coat balanced by the sweeping sky above. Horizontal bands of color in the sky and water create a rhythmic push and pull: the undulating lines mimic the ebb and flow of emotion. Negative space appears minimal, as every inch of the canvas carries pigment or texture, enveloping the figure in an almost claustrophobic embrace. Yet the interplay of the heavy human form against the dynamic environment achieves a tense harmony, underscoring the inevitability of the encounter between inner and outer worlds.

Color and Light

In Despair, color is the primary vehicle of feeling. The sky’s layered bands of red, orange, and yellow blaze across the upper half of the canvas, suggesting both a sunset and an apocalyptic fire. This incandescent light, however, does not illuminate gently; it glares, as though threatening to consume. Below, the water’s swirling purples and blues absorb the heat from above, creating a cacophony of conflicting sensations—warmth and cold, comfort and dread. The figure himself is rendered in muted tones: his overcoat is a deep indigo-black; his face and hands, tinged with sickly greenish-yellow, appear drained of vitality. Munch avoids subtle gradations, instead relying on stark juxtapositions to heighten emotional tension. Here, light and color are not descriptive but expressive, capable of rendering the intangible textures of the human soul.

Technique and Brushwork

Although primarily known for his paintings, Munch often worked in both oil and tempera on canvas, combining mediums to achieve unique textures. In Despair, one discerns both smooth, broad swaths of pigment and more textured, impasto-like passages where the brush’s energy is left visible. The sky’s bands appear to have been applied with a large brush in decisive strokes, while the finer lines of the railing and the figure’s outline betray a steadier hand. This contrast in application reflects the contrast between the uncontrollable forces of nature and the fragile human response. Munch’s technique emphasizes the artwork as artifact: the physical brush marks become traces of his own emotional state, transferring his anxiety onto the canvas. The visible hand of the artist thus becomes part of the painting’s psychological landscape.

Symbolism and Themes

Despair resonates with themes that run throughout Munch’s oeuvre: alienation, mortality, and the psychological interplay between self and world. The railing, both protective and confining, symbolizes the thin edge between stability and collapse. The conflagration-like sky can be read as a projection of the protagonist’s inner inferno. Water, traditionally associated with the unconscious, churns in dissonant patterns that reflect mental turbulence. By uniting these elements, Munch portrays despair not as momentary sadness but as a state that engulfs one’s entire being. At the same time, the painting suggests that such extremity is a defining passage of the human condition—an ordeal that, once witnessed, transforms both subject and observer.

Emotional Resonance

One of the most striking aspects of Despair is its capacity to evoke an almost physical reaction in viewers. The intense palette and dynamic lines trigger visceral responses: hearts may quicken, throats tighten, a sense of unease may settle in the chest. Yet the painting also facilitates a form of empathy: we recognize in the anonymous figure our own moments of helplessness. Munch’s genius lies in this paradox—by depicting the depths of human suffering so unflinchingly, he also offers a kind of consolation: the awareness that despair is a shared experience, a rite of passage in the realm of feeling. The painting thus becomes both mirror and anchor, allowing us to confront our anxieties in a space both terrifying and redemptive.

Despair in Munch’s Oeuvre

Positioned between The Scream and later works such as The Dance of Life, Despair occupies a pivotal place in Munch’s career. It represents a transitional moment when he moved away from overtly figure-based storytelling toward a more integrated fusion of figure and environment. This painting also anticipates the Expressionist movement in Germany, where artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde would adopt similarly bold colors and psychological themes. Yet Despair remains distinctively Munchian: it eschews the frenetic brushwork of some Expressionists in favor of controlled, symbolic structures. As such, it stands as a testament to Munch’s role as both a torchbearer of Symbolism and a harbinger of modern abstraction.

Reception and Legacy

When exhibited in Kristiania and Berlin, Despair contributed to Munch’s growing notoriety. Critics and audiences alike were polarized: some condemned the painting’s stark depiction of anguish as morbid, while avant-garde circles praised its emotional honesty. Over time, scholars have recognized Despair as essential to understanding the evolution of psychological portraiture in art. The work has appeared in landmark retrospectives and academic studies tracing the genealogy of Expressionism. Contemporary artists interested in the intersection of color and emotion often cite Despair as a profound precursor, emphasizing its pioneering use of hue to encode psychic states. The painting’s legacy endures in the continued exploration of art’s capacity to externalize the invisible terrain of human suffering.

Conclusion

Edvard Munch’s Despair transcends its 1894 origins to speak to the enduring human experience of existential crisis. Through a masterful fusion of symbolic composition, raw color, and expressive technique, Munch renders the abstract reality of emotional collapse into a tangible visual encounter. The painting confronts us with the fragility of the self and the relentless power of nature as emotional mirror. Yet it also offers a communal space for reflection: by witnessing the figure’s profound solitude, we recognize our own moments of despair and find, paradoxically, solidarity in shared vulnerability. Despair thus remains a cornerstone of modern art—a work that defines not only an artist’s inner world but also the universal contours of human feeling.