Image source: wikiart.org

First Encounter With A Night Of Weight And Mercy

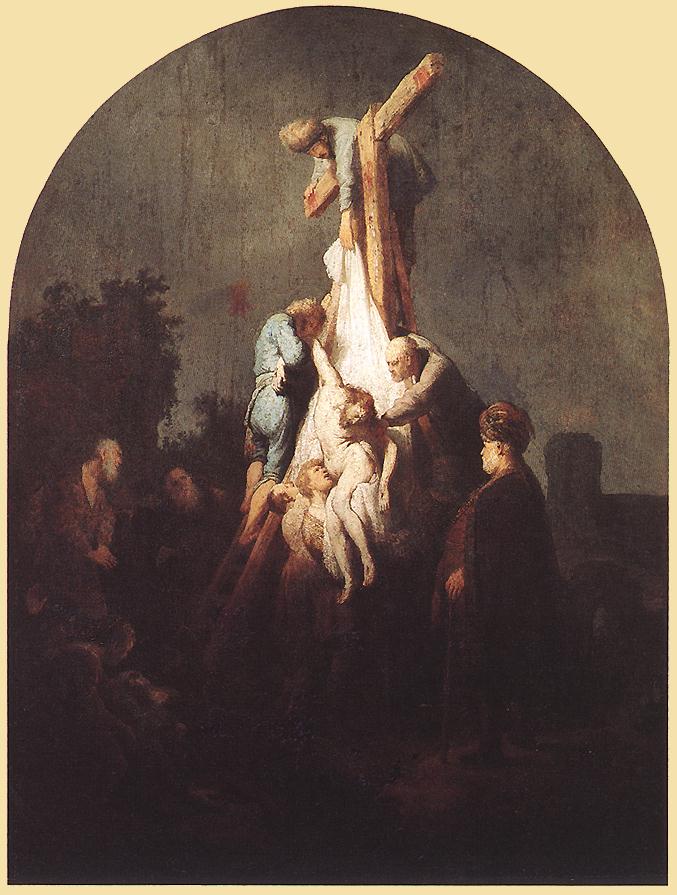

Rembrandt’s “Deposition from the Cross” (1634) opens like a slow breath after storm. In the arched panel, a knot of figures gathers around the cross to lower Christ’s body. Darkness presses from every side, but the center glows with a pale, troubled light that catches linen, skin, and the rough timber. The scene is not a spectacle of grief; it is a labor. Strained shoulders, braced knees, and careful hands choreograph the descent. The painting’s first gift is tactile: you feel the weight being negotiated. Its second is spiritual: you sense a community learning how to hold sorrow together.

A Composition Built On Ladders, Ropes, And A Diagonal Of Descent

The architecture of the picture is a great diagonal that runs from the cross-beam down through the white shroud to the men receiving Christ below. Rembrandt stacks ladders like scaffolds of compassion, each rung a foothold in the tender work. From above, a figure leans over the beam, guiding the linen; halfway down, another braces his hip against the wood; below, two men cradle the body as it turns from tautness to slack. This cascade of bodies creates a visual sentence: from height to earth, from death’s public stage to the arms of friends.

Chiaroscuro As Moral Weather

Light is selective, partisan, ethical. It finds Christ’s torso and legs, the shroud’s bright run, the faces bent in concentration, and the hands that do the lifting. Everything else—landscape, onlookers, night sky—recedes into a hum of browns and smoky grays. Rembrandt’s darkness is never empty; it is a room in which mercy can be heard. By letting light cling to work rather than to architecture, he converts the scene from pageant to practice. The night is not conquered; it is answered by care.

The Shroud As A River Of Action

That luminous cloth is the painting’s engine. It carries the eye from the cross-beam down to the receiving arms, turning a static subject into movement. Streaks of warm white thicken where the fabric bears weight, then thin out as it passes through open air. You can feel the give of linen around a shoulder blade, the drag where it catches on a nail, the sudden slack when a knot is released. The shroud is a verb, not a prop.

Christ’s Body And The Ethics Of Tender Realism

Rembrandt rejects both heroic rigidity and decorative languor. The body is heavy with the plausible looseness of death; the head lolls; the knees unhinge; the torso turns as gravity dictates. Yet nothing is morbid. The pallor carries a faint warmth, as if the skin still remembered blood. The painter’s compassion is anatomical: he paints what hands would know. That fidelity dignifies the scene, because love meets truth without flinching.

Hands That Think Before The Mind Can Speak

Trace the hands and the whole narrative resolves. One figure secures the linen high on the beam. Another steadies Christ’s arm so it will not strike the ladder. Below, a man cups the ribcage while a companion supports the thighs. Off to one side, a woman’s fingers bunch the dark veil at her mouth. The gestures are specific, unsentimental, and persuasive. The painting suggests that in the aftermath of catastrophe, hands learn first what must be done.

Ladders As Instruments Of Compassion

The ladders read like makeshift liturgy. Their legs bite into the ground; their tops wedge between wood and sky. On them, the helpers ascend not to perform, but to serve. The ladders give the scene a pyramidal steadiness that keeps grief from collapsing. They also visualize the journey from public humiliation to private mourning. The body travels down a path of rungs rather than being wrenched free; descent replaces spectacle.

Faces In Different Weathers Of Grief

Rembrandt refuses to stamp a single emotion across the crowd. A man in profile concentrates with his jaw set, not yet allowing sorrow to flood his task. The Magdalene-like figure at lower right bends inward, her head a dim oval of prayer. An older man stands aside, hands clasped, as if curating strength for what comes next. Each face inhabits a different minute of lament, and together they make a clock of mourning that tells a truthful time.

The Arched Top And The Sense Of Chapel

The panel’s rounded crown frames the action as altarpiece rather than anecdote. The arch carries a hushed architectural memory, as if we viewed the scene from within a chapel recess. That shape also disciplines the composition. The diagonal of descent must bend to the curve, so the whole image feels gathered, not sprawling. The arch is a shelter for the eye and a soft pressure that keeps the drama human-scaled.

Color Held In Reserve For Maximum Gravity

The palette is a language of browns, blue-grays, and muted reds. Rembrandt refuses frivolous brilliances; he wants the color to serve weight and skin. The small cool notes in garments—the blue on a climber’s sleeve, the ashy green in a cloak—cool the shroud’s brightness so it remains solemn. A warmer accent at the lower right pools like a banked ember, balancing the composition. Because color is modest, value carries meaning, and light’s moral becomes legible.

The Cross As Machine And Memory

The rough timber is pictured as a tool already used to the point of exhaustion. Splinters catch light along the edges; iron spikes scar the surface; ropes abrade the grain. The cross is not a symbol floating free of facture; it is carpentry. As such it binds heaven to earth with joinery, not rhetoric. It remembers the workmen who raised it and now sees the community that undoes their labor with gentler hands.

The Crowd At The Edges And The Silence Of Witnesses

Shadowed figures cluster at lower left, their heads tilted upward like stones warmed by breath. They do not intrude; they hold space. The painting understands that some griefs require watchers as much as workers. To stand, to see, to keep still—these quiet acts build the room in which care can happen. Rembrandt grants them dignity by letting them belong to the dark that protects the event rather than stealing light for themselves.

Gravity As The Unseen Protagonist

Everything visible is conversing with gravity. Knees bend, ropes tighten, linen stretches, bodies brace. The painter makes physics emotional. You feel the bounce when a knot passes over a beam, the drag of cloth turning under weight, the sudden sweep when the torso clears the ladder. The brinksmanship of balance keeps the eye alert. The path from wood to earth is both dangerous and inevitable, and that tension sharpens reverence.

A Rhythm Of Triangles That Holds The Eye

Look for triangles: the angle of the cross, the splay of ladders, the wedge of shroud, the grouping of men below. These interlocking shapes establish order inside chaos. They create stations for the gaze: top beam, midpoint knot, receiving arms, bowed figures. The rhythm slows looking to the tempo of careful work. You do not skim the picture; you descend it step by step as the helpers do.

Echoes Of Earlier And Later Deposition Scenes

Rembrandt knows the tradition—Rogier van der Weyden’s crystalline grief, Rubens’s muscular theater—and chooses a third path: intimate labor in deep night. He borrows Rubens’s shroud-as-ramp idea but removes baroque polish, replacing it with breath and strain. He retains Northern devotion’s seriousness without freezing faces into emblem. The result is not anti-traditional; it is tradition brought to human temperature.

Paint That Records Touch

Up close, the surface is a ledger of sensations. Scumbled passages in the background give the night a breathed-on softness; thicker highlights on shroud and flesh crest like foam on a swell; wiry brushwork on hair and beards briskly marks individuality. The paint never turns slick. It keeps the small frictions that make tactile truth, as if Rembrandt wanted the viewer’s fingertips to know what the participants’ hands feel.

Theological Focus Without Emblematic Noise

No angels hover, no putti present crowns, no allegorical figures clutch instruments of Passion. The sacredness is carried by attention and touch. The body is treated with more reverence than any symbol could command. In doing so, the painting argues a doctrine without writing it: love is learned by caring for what is heavy and real.

The Women As Keepers Of Continuity

While the men strain at ladders, the women shape the future of the scene—anointing, washing, wrapping. Even when shadowed, their silhouettes hold calm. A veiled figure at the right squared to the viewer reads as a steward of ritual, her stillness a counterweight to the men’s motion. Rembrandt often composes with this gendered duet: action and tending, muscle and memory, both necessary, both honored.

Landscape As A Low, True Murmur

Beyond the cross, low silhouettes of trees and a ruin rim the horizon in umber twilight. They do not compete; they testify. The world continues even as this body is lowered. The murmur of nature is not indifference; it is time’s steadying sound. Against it, the bright human work becomes more precious.

The Arduous Beauty Of Coordination

What makes the picture moving is not only compassion but coordination. Four or five people must think as one, time their grips, feel the same weight. The painting becomes an ethics lesson disguised as choreography: goodness is often collective timing. Rembrandt composes that truth without preaching it. You learn it with your eyes as the figures lean in the same direction.

1634 And The Young Master’s Drama Of Human Scale

Created during Rembrandt’s energetic early Amsterdam years, the work shows a painter already sure of how to stage biblical gravity in domestic optics. He has Caravaggesque chiaroscuro at his disposal and the Northern love of graphic truth, but he refuses mere effect. The scale remains intimate; the hero is a task completed well. It foreshadows his later, even deeper descents into human interiority.

The Viewer’s Position At The Foot Of The Cross

The composition leaves an opening at the lower edge where the receiving figures make room. That is where you stand. The painting does not place you above, surveying; it invites you under, assisting. Your eyes take the descent personally, measuring the fall of the torso, predicting how your own hands would adjust. It is a humbling viewpoint that turns spectators into imagined helpers.

Aftermath Foreshadowed In The Poses

You can already see the next minutes: the body swaddled, the women bearing spices, the slow procession into a garden tomb. Christ’s sagging limb seems to point toward the ground where rest awaits. The helpers’ faces say the work will continue through the night. Rembrandt composes a still image that vibrates with time before and after.

Why The Painting Still Feels Contemporary

The scene speaks to anyone who has ever carried a stretcher, borne a coffin, or helped move the unwell from bed to chair. It understands that love often looks like logistics. The painting honors those midnight crews who lift and lower with patience. Its darkness resembles hospital corridors at 3 a.m., its light the small circle that labor creates. That human truth keeps the work fresh.

Closing Reflection On Descent, Dignity, And The Light That Stays

“Deposition from the Cross” is a hymn to careful strength. Rembrandt gives the world’s heaviest story the only ending humans can provide before dawn: lower the body, wrap it well, hold each other up in the dark. The shroud cascades, hands answer, and light attends the places where people do what must be done. The painting does not resolve grief; it teaches reverence for the labor that makes grief bearable. In that reverence glimmers a promise: what is handled with such dignity is not finished here.