Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context: The Dawn of Sound Film

In 1927, the cinematic world stood on the threshold of transformation. The silent picture, accompanied by live orchestras or phonograph records, had reigned unchallenged for decades. That year, Lee De Forest’s Phonofilm process emerged as one of the earliest commercially viable systems for synchronizing sound directly onto film. Exhibitors and audiences alike buzzed with anticipation: could this new technology finally marry image and voice, music and motion? Commissioned to promote De Forest’s groundbreaking invention at trade shows and usher-in events, Alphonse Mucha—already in his eighth decade—created a poster that both celebrated the modern miracle of recorded sound and embodied the enduring elegance of his Art Nouveau style.

Alphonse Mucha’s Late-Career Style Evolution

By the 1920s, Mucha had long since moved beyond Parisian theater posters into a broader decorative and fine-art practice. His trademark “whiplash” curves and ornate floral motifs remained, but his palette had gently shifted toward softer, more pastel-infused hues. The once-bold outlines of his 1890s masterpieces gave way to more fluid, ethereal linework, suggesting the dematerializing effect of sound waves. Mucha’s late period also saw him experimenting with chromolithography alongside watercolor studies, pushing the boundaries of print technology to capture iridescent and metallic effects. De Forest Phonofilm exemplifies this mature synthesis: a technical commission rendered with the lyrical grace of a private allegory.

Commission and Intended Function

Lee De Forest recognized Mucha’s international reputation and decorative mastery as invaluable marketing assets. The De Forest Phonofilm Company contracted Mucha to design a large-format poster that could appear in cinema lobbies, industry journals, and trade-show booths. The poster needed to convey three core messages at a glance: the novelty of sound-on-film technology, its technical sophistication, and its promise of elevated entertainment. Mucha’s challenge was to transcend mere schematic diagrams or rote typography and craft an image that would resonate emotionally while still appearing cutting-edge.

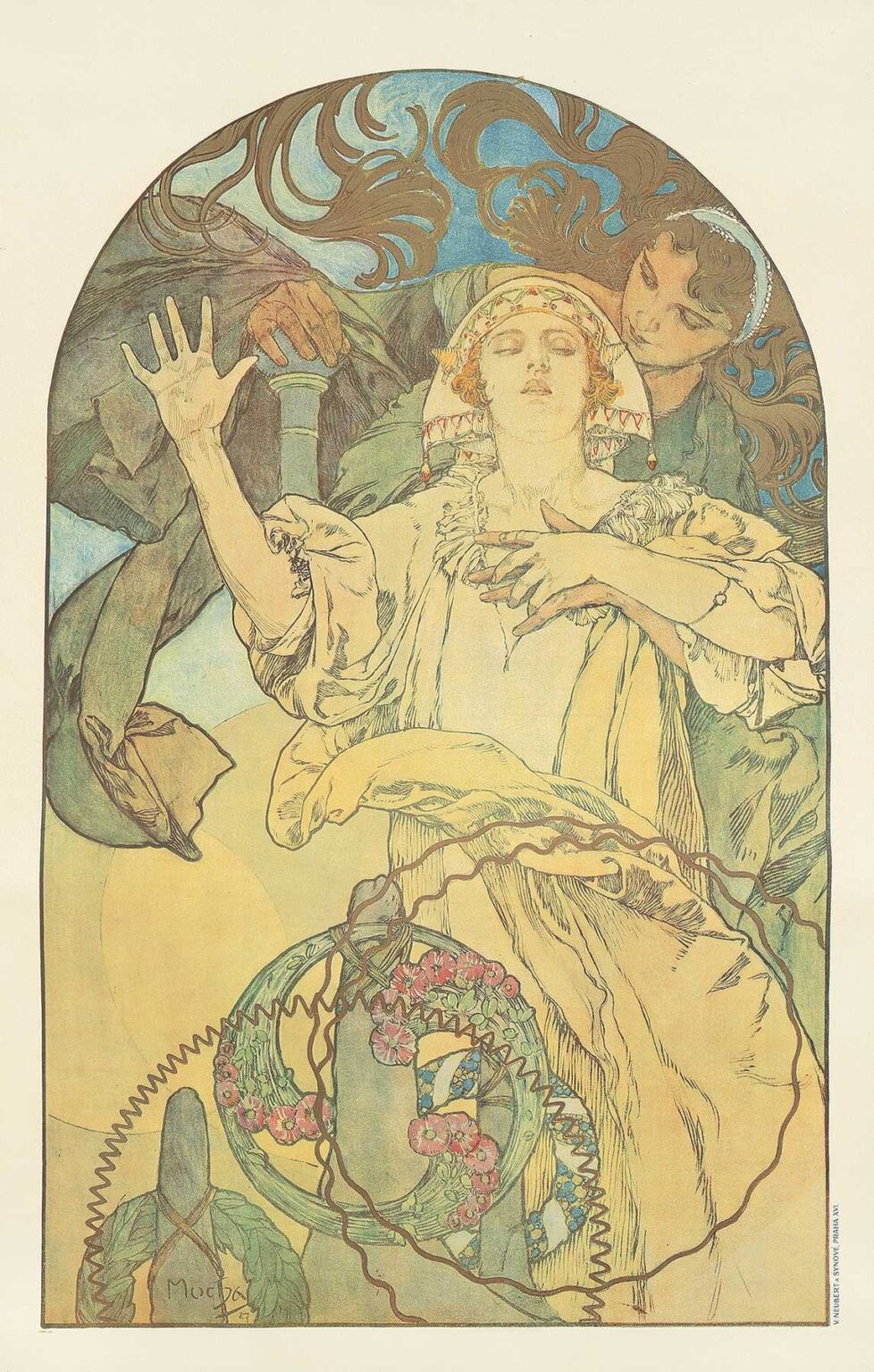

Subject Matter: Allegory of Sound Made Visible

Rather than depict a projector or technical diagram, Mucha chose to personify sound itself. At the poster’s center stands a graceful female figure—the “Goddess of Sound”—draped in diaphanous robes that billow like acoustic ripples. Her arms are outstretched, palms turned skyward, as though she is conducting the very air. From her open hands emerge sinuous, ribbon-like tendrils that coil through the composition, symbolizing phonographic waves traveling across celluloid. Surrounding her are musical instruments—a lyre, a clarinet, and a horn—each subtly integrated into the swirling ornament. The woman’s tranquil expression and upward gaze suggest both reverence for technology’s potential and the sublime emotional power that recorded sound can unlock.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Mucha organizes De Forest Phonofilm within his characteristic arched cartouche, echoing the formats of his earlier theater posters yet adapted for modern sensibilities. The arch frames the central figure and provides a contained stage on which her undulating forms can play. Vertically, the composition flows from the poster’s title band at the top—“De Forest Phonofilm”—down through the figure’s lifted arms and into the intertwined sound-ribbons and instruments at mid-height, culminating in the company name and technical tagline at the base. Diagonal gestures—her elongated sleeves, the curving ribbons, and the angled instruments—generate a dynamic tension that conveys movement. Negative space around the arch and within the lower text area ensures legibility while accentuating the lyrical central tableau.

Typography as Decorative Element

Mucha believed that lettering should harmonize with imagery rather than float above it. For De Forest Phonofilm, he devised a bespoke typeface: tall, elegant serifs with subtle flares and occasional organic flourishes that mimic the poster’s whiplash curves. The title at the top appears in deep bronze ink, its letters veined with lighter highlights to suggest the pulsing of sound waves. This treatment allows the type to catch light and draw the eye without overpowering the figure. Beneath the Goddess of Sound, the phrase “Sound-on-Film Process” appears in a smaller yet equally stylized font, anchoring the technical claim within the overall decorative flow. Mucha’s fusion of text and image exemplifies his conviction that marketing copy can itself be a work of art.

Color Palette and Light Effects

By 1927, Mucha’s palette had mellowed from the jewel-like primaries of his heyday to a more nuanced scheme of pastel golds, pale teals, muted rose, and soft grays. In De Forest Phonofilm, a warm ivory ground allows translucent lithographic inks to glow. The Goddess’s robes unfold in pale gold and silvery grays, while the sound-ribbons shimmer in mint greens and pastel blues. The instruments gleam in subtle metallic bronze, reflecting the era’s fascination with machine-age materials. Mucha used a combination of matte and metallic inks: the matte colors provide depth and mass, while bronze and silver inks—applied in selective passes—catch ambient light, evoking the glint of a projector’s lens or the sheen of a phonograph horn. This interplay of optical effects underscores the poster’s theme of technological marvel.

Line Work and the “Whiplash” Curve

Central to Mucha’s visual brand is the “whiplash” or “coup de fouet” line—a seamless, undulating contour that suggests organic growth and dynamic energy. In De Forest Phonofilm, these lines animate the figure’s hair, sleeves, and the emanating sound-ribbons. Instruments too are rendered with gently curving outlines rather than rigid technical schematics, emphasizing their transformation from mere objects into carriers of spirit and music. Mucha modulates line weight: bold strokes define the figure’s silhouette and major folds, medium lines contour the instruments, and fine lines articulate details—finger joints, floral hair ornaments, and the delicate perforations along the sound ribbons. The result is a composition that feels both highly stylized and organically alive, as though sound itself were made visible.

Iconography of Technology and Music

Mucha selectively incorporates emblematic cues to signal the Phonofilm process without resorting to literal photography equipment. The swirling ribbons double as both sound waves and the filmstrip’s unspooling reel. A stylized microphone grille appears subtly woven among the ornamental vines in the lower field, suggesting the device by which sound is captured. The lyre, clarinet, and horn represent music’s ancient lineage, now modernized through De Forest’s invention. By personifying sound and integrating these musical icons, Mucha places the viewer at the intersection of tradition and innovation—inviting them to marvel at how human creativity can now be preserved and replayed.

Technical Lithography and Craftsmanship

Creating a poster of this complexity in 1927 required a close collaboration between Mucha and the Champenois lithographic workshop. Mucha first prepared a full-scale watercolor and pencil study, mapping out color zones and ornamental details. That study was transferred—via chalk dust or direct crayon transfer—to multiple limestone plates or zinc litho stones, with each plate corresponding to one or more colors: ivory highlights, pale golds, minty greens, metallic bronzes, and black outlines. Printers used registration pins to align successive impressions precisely. Metallic bronze and silver inks were mixed to exact pigment ratios, ensuring consistent reflectivity. The final prints exhibit the characteristic warmth, gloss, and layered translucency for which Mucha’s work is celebrated—an artisanal masterpiece born of industrial process.

Reception and Impact on Sound Cinema Promotion

Upon its debut at the 1927 New York Film Exposition and subsequent trade shows, Mucha’s De Forest Phonofilm poster drew immediate acclaim. Film exhibitors praised its romantic evocation of sound’s magic, noting that it captured audience imagination more effectively than dry technical diagrams. Trade publications such as Exhibitors Herald and Motion Picture News featured the poster in their advertising supplements, citing its artistic merit and promotional efficacy. The image helped position Phonofilm as both a technical solution and a cultural phenomenon, paving the way for subsequent sound-on-film systems like Vitaphone and Movietone. Even as newer technologies emerged, Mucha’s poster remained a touchstone for the emotional promise of “talking pictures.”

Influence on Graphic Design and Art Deco Transition

While rooted in Art Nouveau, De Forest Phonofilm hints at the emerging Art Deco aesthetic with its streamlined forms, emphasis on metallic inks, and subtle mechanistic references. Younger designers in the late 1920s and 1930s looked to Mucha’s poster for cues on integrating technology into decorative graphics. The poster’s combination of allegorical figure, geometric frame, and metallic sheen influenced magazine covers, product packaging, and theater marquees throughout the Jazz Age. Even as Art Deco ascended with its bolder geometry and brighter palettes, Mucha’s late-career poster remained admired for its harmonious fusion of tradition and modernity.

Legacy and Preservation

Original prints of De Forest Phonofilm are now rare treasures held in major poster collections—such as the Musée d’Orsay (Paris), the Library of Congress (Washington, D.C.), and private archives devoted to film ephemera. Conservation efforts encounter challenges: the mixed litho and metallic inks can flake under poor humidity control, and the paper ground may absorb atmospheric pollutants. Modern archivists employ deacidification, careful humidity regulation, and UV-filtered display lighting to preserve the poster’s vibrancy. Digital high-resolution scans ensure broader public access while protecting fragile originals. Film and design historians continue to study Mucha’s poster as a benchmark in combining commercial promotion with high art.

Conclusion: Art, Technology, and the Human Voice

Alphonse Mucha’s De Forest Phonofilm poster transcends its role as mere advertisement to become an enduring symbol of technology’s ability to amplify human expression. Through its allegorical personification of sound, sinuous Art Nouveau curves, and luminous palette, the image captures the wonder of recorded voice and music emerging from celluloid. Mucha’s late-career mastery—his refinement of line, color, and ornament—creates a visual metaphor for sound captured, preserved, and replayed. More than ninety years later, De Forest Phonofilm stands as a testament to the transformative power of invention and the enduring beauty of decorative art at the intersection of tradition and innovation.