Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

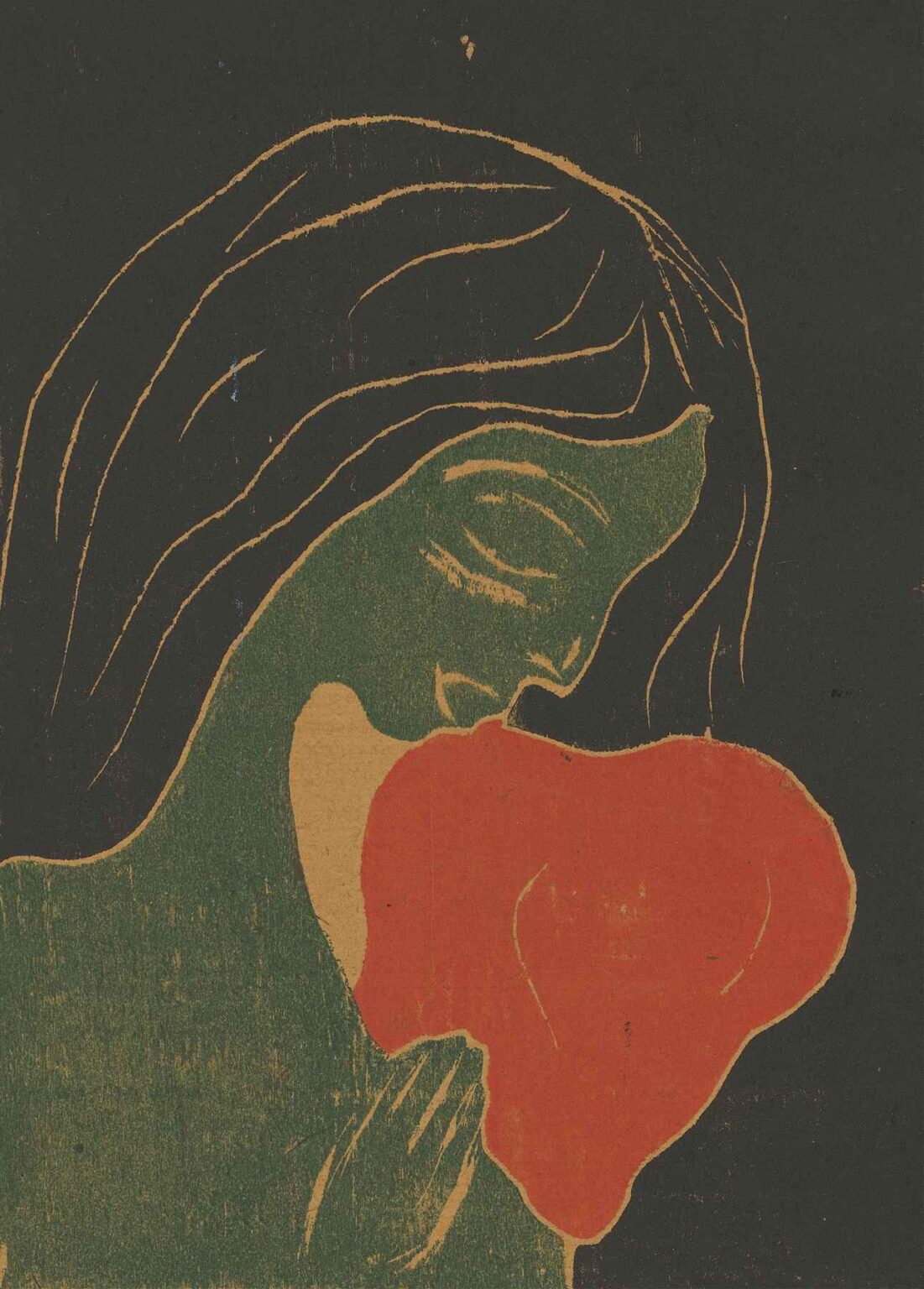

Edvard Munch’s Das Herz (The Heart), executed in 1899, stands among his most intimate and evocative explorations of human emotion. At first glance, the work presents a simplified female figure rendered in muted, earthen tones, gently bowing her head toward a vibrant red form that occupies the lower right quadrant of the composition. The red shape, ambiguous in its contours yet unmistakably organic, suggests both the physical organ and the intangible seat of feeling. Through deliberate formal choices—flattened perspective, stark outlines, and a restricted palette—Munch distills the drama of human inner life into its purest visual symbols. The work embodies the core preoccupations of his art at the fin de siècle: the intertwining of love and pain, the tension between bodily experience and psychological depth, and the powerful ambiguity of representation itself.

Historical Context

By 1899, Munch was firmly established as one of the leading voices of European Symbolism, a movement committed to externalizing inner states rather than depicting objective reality. In the decade preceding Das Herz, he had produced The Scream (1893), The Madonna (c. 1894–95), and numerous lithographs and woodcuts centered on anxiety, desire, and mortality. These works generated both acclaim and controversy when exhibited in Berlin and Kristiania (now Oslo), provoking intense reactions to their raw emotional charge. In Norway, Munch’s candid exploration of sexual desire and psychological suffering ran counter to prevailing bourgeois norms, leading to censorship and heated debate. Abroad, however, his paintings and prints captured the burgeoning Expressionist impulse, influencing artists such as Wassily Kandinsky and the Berlin Secessionists. Das Herz emerged at a moment when Munch was synthesizing his pictorial language—combining the immediacy of printmaking with the symbolic potency of color and form—to articulate a universal narrative of human vulnerability.

Subject Matter and Iconography

Das Herz eschews explicit narrative in favor of potent symbols. The central motif—the heart—appears as a singular, pulsating presence rather than tied to a literal scene. Its swollen, almost floral silhouette seems to hover like a living entity separate from but inextricably linked to the female figure. The woman’s bowed posture and the angle of her face imply an act of offering or intimate communion. Her closed eyes and the subtle curve of her lips suggest introspection, perhaps mourning or an act of remembrance. The absence of obvious setting or descriptive detail universalizes the motif: the spectator is invited to project personal associations—love, loss, longing—onto the tableau. By presenting the heart as both gift and burden, Munch invokes centuries of artistic and literary traditions while distilling them into elemental, archetypal imagery.

Composition and Form

Munch’s compositional strategy in Das Herz relies on bold contours and a flattened spatial organization that rejects conventional perspective. The woman’s profile, delineated by a single unbroken line, occupies the left flank of the image, guiding the viewer’s eye toward the heart motif. Negative space around the heart intensifies its visual prominence, while the nearly monochromatic background serves as a void against which figure and symbol glow. The tension between the fluid curves of the form and the rigid silhouette of the silhouette creates a dynamic interplay: the heart, though static, seems to pulse within this spatial tension. The composition balances diagonals (the woman’s tilt, the heart’s leaning axis) and verticals (the figure’s neck, hair strands) to achieve a rhythmic harmony, lending the scene both stability and restless energy.

Color and Light

Color in Das Herz is inherently symbolic. The almost somber olive-green of the figure’s body and hair suggests twilight or pallor, evoking decay or introspection, while the golden outlines impart a sense of ethereal light. This luminous contouring recalls the halo effect of religious art, nodding to the sacred quality Munch attributed to emotional experiences. In stark contrast, the vermilion heart dominates the visual field, radiating heat and immediacy. The red is uncompromising—neither shaded nor modulated—so that it registers as a pure declaration of feeling. The minimal interplay of hues heightens the psychological drama: the painting’s darkness becomes the psychological backdrop in which the heart’s color-language speaks most urgently. Munch does not model forms through gradations of light and shadow but uses color as sculptural force.

Symbolism and Themes

At the heart of Munch’s work lay themes of love, suffering, and existential crisis, and Das Herz unites these concerns in a single symbol. The heart has long signified emotion and vitality in Western art, yet Munch’s representation is neither sentimental nor anatomical. Its shape is intentionally ambiguous—both fragile and resilient, organic and otherworldly. One may read the piece as an act of offering: the figure presents her heart, in full view, to an unseen recipient. Alternatively, the sense of inward turning suggests self-confrontation, as if the woman contemplates the cost of feeling. Munch’s lifelong fascination with the interplay of desire and death resonates here: love is portrayed as an act of vulnerability that carries within it the possibility of devastation. The viewer becomes witness to a profoundly human moment, one in which the boundaries between self and symbol, body and psyche, are both asserted and blurred.

Technique and Style

Although Munch is often celebrated for his oil paintings, Das Herz demonstrates his mastery of print media, likely executed as a woodcut or lithograph, which he favored around 1899. The technique demands decisiveness: every carved line or inked contour is irreversible, mirroring the irrevocability of intense emotional experiences. The slightly textured surface—revealing the grain of the printing block—adds a tactile dimension, akin to scars or skin. Munch’s choice of medium underlines the unity of form and content: the artist’s hand is evident in the occasional uneven patch of pigment, evoking the quiver of a pulse. His line-work, both spare and expressive, suggests the influence of Japanese prints (which he collected) as well as the flowing linearity of Art Nouveau. The outcome is a pared-down design that nonetheless throbs with psychological and material presence.

Emotional Resonance

Das Herz occupies a liminal space between abstraction and figuration, allowing viewers to project their own emotional histories onto the image. The figure’s serene yet somber mien resonates with universal experiences of love’s joys and sorrows. The absence of extraneous detail eliminates distraction, compelling an encounter that feels at once personal and archetypal. Many observers report a sensation of being drawn into a quiet dialogue with the work: the visual economy of line and color encourages contemplation, while the central motif pulses with emotional urgency. Munch’s ability to externalize internal states—often described as “inner landscapes”—finds one of its purest expressions here. The silence of the scene becomes almost audible, like the beat of a heart in still air.

Das Herz in Munch’s Oeuvre

Within the broader context of Munch’s career, Das Herz represents both continuity and refinement. It synthesizes motifs from earlier works—such as the embrace of The Kiss (1897) and the ecstatic reverie of The Madonna—while intensifying the graphic clarity he achieved in his print series. Around this time, Munch was experimenting with a “frieze of life,” a series of prints and paintings chronicling the human cycle from birth to death. Das Herz stands at the fulcrum of that cycle, embodying the emotional apex between innocence and decay. Its distilled power also anticipates the bold color experiments of early Expressionism, marking Munch as a precursor to artists who would explore the relationship between color and psyche in the decades to come.

Reception and Legacy

When first exhibited, works like Das Herz provoked strong reactions. Contemporary critics in Berlin and Kristiania alternately praised Munch’s honesty and decried what they saw as moral transgression. Over time, however, the painting has come to be recognized as a landmark of modern art. It has been included in retrospectives exploring Munch’s influence on German Expressionists and Scandinavian Symbolists alike. Scholars often cite Das Herz as evidence of Munch’s radical formal economy: how little he needed to convey overwhelming emotion. The motif of the heart has been revisited by later artists exploring figurative minimalism and psychological portraiture, from the Fauves to post-war abstract painters. Its legacy endures in the ways subsequent generations understand the capacity of art to embody interior life.

Conclusion

Edvard Munch’s Das Herz remains a testament to the power of reductive form and expressive color to evoke the depths of human feeling. Through its spare composition, symbolic clarity, and rich emotional undertones, the work crystallizes the artist’s lifelong exploration of love, loss, and the existential weight of the human heart. Without reliance on narrative detail or dramatic gesture, Munch compels viewers into intimate encounter—drawing us into the space between form and feeling, between viewer and viewed. More than a period piece of the 1890s, Das Herz resonates today as a universal meditation on vulnerability and the transformative potential of art to make visible what lies at the core of our shared humanity.