Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

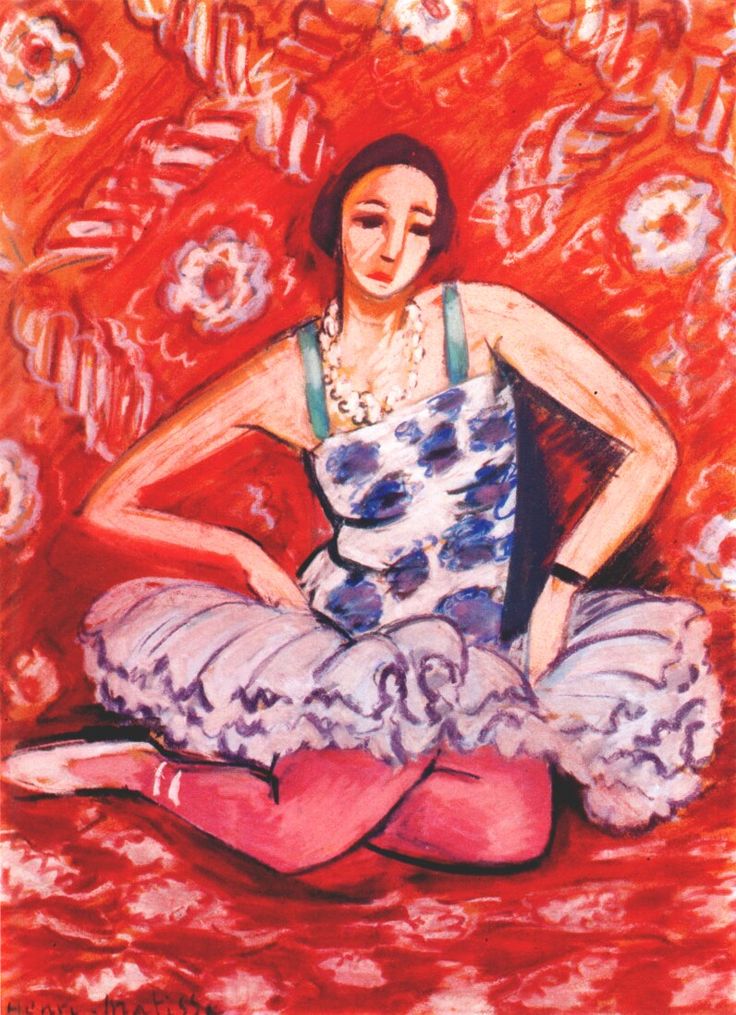

Henri Matisse’s “Dancer” (1925) is a concentrated burst of theater staged inside the decorative world of his Nice years. A young performer sits on the floor in a short tutu and pink tights, her torso wrapped in a blue-spotted bodice with green straps, the entire figure set against a vibrating field of red patterned with floating white forms. The costume, the pearls around her neck, and the studiously casual pose announce the subject as a modern entertainer, yet the deeper drama is pictorial: Matisse composes color, pattern, and contour so that the dancer’s body becomes one instrument among others in a visual orchestra. The painting is less about a specific performer than about performance itself—how poise, rhythm, and repetition can be translated from stage to canvas.

The Nice Period and a Theater of Interiors

By 1925 Matisse had fully embraced the Mediterranean light and controlled environments of Nice. He arranged rooms like sets, populating them with textiles, screens, flowers, instruments, and models. The aim was not illusionistic depth but a harmonious surface where color and pattern could be orchestrated. “Dancer” belongs to this interior theater, yet it carries the charge of the city’s flourishing performance culture—music halls, ballet companies, and cabarets that lent the artist both motifs and attitudes. Here the room is more backdrop than place, a saturated red field that turns the figure into a protagonist in a drama of chromatic relations.

A Pose That Choreographs the Rectangle

The dancer sits with one knee folded under her, the other bent forward, arms set akimbo to fluff the tutu. Her head tilts with a quiet resolve, eyes lowered and lips composed, a mask of professional self-possession. This pose is a choreographic solution to the vertical rectangle. The triangular spread of the tutu establishes a central fan shape; the bent legs create counter-triangles that keep the image from collapsing into symmetry; the arms form diagonal braces that echo the sides of the canvas. The entire figure reads like a living ornament whose curves, angles, and pauses are tuned to the painting’s limits. It is a pose to be seen rather than a gesture caught in motion, a performer’s stillness between sequences.

Color as Stage Lighting and Script

Color directs the action. The dominant red behaves like stage lighting, bathing every other tone in warmth. It is not a single red but a chorus of oranges, crimsons, and coral pinks that flicker across the patterned ground and wall. Against this heat, Matisse introduces cooling agents: the blue spots on the bodice, the pale lilac of the tutu’s ruffles, the green straps that frame the shoulders. The dancer’s skin takes on a peach-rose tint, picking up reflections from the red environment while retaining its own softness. Black, used sparingly around the eyes and to articulate seams and shadows, punctuates the field like a conductor’s baton, telling the eye where to rest before moving on.

Pattern as Pulse and Atmosphere

The red backdrop is alive with white rosettes and calligraphic swirls that float rather than sit. These motifs supply the picture’s pulse, a repeating beat that operates behind the figure the way music surrounds a performer on stage. Pattern also flattens the space so that the dancer does not recede into a room but seems to hover on the painting’s surface. This productive flatness is central to Matisse’s practice. It ensures that the subject is not lost in anecdotal surroundings; instead, she shares the same decorative logic as the ground that carries her. The drama arises from how the cool, structured tutu interrupts and coexists with the warm, undulating backdrop.

Contour, Drawing, and the Expressive Edge

Matisse’s line is firm, elastic, and strategically simplified. The oval of the face is encased in a decisive contour that holds the features like a cameo. Around the shoulders and arms the line thickens and thins with the turn of form, never resorting to heavy modeling. The tutu’s scalloped edge is drawn as a sequence of quick, rhythmic arcs, each one a little different, so that the frill feels animated yet controlled. This calligraphic, breathing contour transforms drawing into choreography. Edges are not merely boundaries; they are tempo and phrasing, telling us how to move through the image.

Fabric, Costume, and the Intelligence of Materials

Matisse never paints costume as a mere pretext for color. He attends closely to the nature of materials. The tutu reads as layered tulle because its ruffles are given as translucent, overlapping strokes that let warmer underlayers glow through. The bodice looks dense and slightly glossy thanks to thicker, flatter touches of blue resting on white. The pearls around the dancer’s neck are not meticulously detailed; they are small, luminous ellipses that convince because they behave like paint and like pearls simultaneously. The result is a tactile atmosphere that matches the sensuality of performance without falling into illusionism.

The Face as Mask and Modern Identity

The dancer’s face is both specific and emblematic. Her brows and eyelids are accentuated, the features simplified into clear planes that recall the cosmetic masks of the stage. She looks down, as if considering the step to come or listening for her cue. This inward gaze shields the painting from voyeurism. The figure is not offered to the viewer as an object of consumption; she is absorbed in her role, a professional at work. At the same time, the masklike treatment situates her inside a modern world where identity is performed, adjusted, and stylized. Matisse captures this paradox without anxiety: the face is humane and theatrical at once.

Decorative Space and the Ethics of Pleasure

One of the Nice period’s most important contributions is its argument that decoration can be ethical, that pleasure can be rigorous rather than trivial. In “Dancer,” pleasure is built from discipline: the careful balance of hot and cool, the measured repetitions of pattern, the tuned intervals between dark accents. The painting asserts that beauty is not a byproduct of indulgence but a form achieved through relation. The dancer’s profession mirrors this truth. Her easy grace is the outcome of practiced control; her costume’s extravagance is held together by structure. The canvas becomes a proposition about how to live with delight responsibly.

Dialogue with the Ballet and the Music Hall

Although Matisse did not set out to document a specific troupe, the painting resonates with the culture of Parisian dance in the 1920s. The Ballets Russes had transformed costuming and choreography; music halls and theaters offered new images of glamour and movement. Matisse absorbs these influences selectively. Instead of depicting a leap or a complicated stage set, he compresses performance into a single poised instant, emphasizing costume, posture, and the concentrated self-possession that precedes action. In doing so, he aligns himself with modern choreographers who valued clarity and line, translating their concerns into chromatic and surface terms.

Comparisons within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Dancer” converses with other Nice interiors in which a figure sits amid patterned textiles—odalisques reclining on striped couches, women practicing music against coral walls, models in white lingerie framed by open windows. The red ground here recalls the sumptuous wallpaper of works like “Woman at the Piano,” while the frontal, centered figure echoes the strong hieratic compositions of earlier Fauvist portraits. It also prefigures the later paper cut-outs, where figures and grounds are reduced to flat, interlocking shapes. The relation is not one of influence but of sensibility: a consistent belief that a picture can be built from bold silhouettes and carefully tuned color chords.

Movement Without Motion

The dancer does not leap, spin, or extend; yet the painting is full of movement. The scalloped tutu vibrates; the rosettes seem to drift; the arcs of the arms promise unfolding. This is movement conceived as potential rather than as spectacle. The stillness allows the viewer to register subtle forces—a pull from shoulder to wrist, a sway in the torso, a spring coiled in the bent leg. It mirrors the concentrated pause before a phrase in music or a step in choreography. In this way Matisse aligns his art with the temporality of rehearsal and preparation, states of focus that professionalize emotion.

The Role of Black and the Logic of Accents

Black is sparsely but strategically used: around the eyes to sharpen expression, in slender lines along the straps and seams, and beneath the tutu to anchor volume. These accents prevent the painting’s warm sea from dissolving into softness. They give edges authority and keep the ornament readable. The logic is musical. In a bright key, the painter supplies a few low notes so the chord has depth. The result is a picture that is luminous but not weightless.

Modern Femininity and Agency

Matisse’s dancer is glamorous, but she is not a fantasy odalisque nor a passive muse. She occupies the center with agency, hands on tutu, body organized for work. The pearls and makeup are professional equipment as much as adornment. She belongs to a modern labor force of performers whose skill is to make difficulty look effortless. The painting recognizes and honors that craft. Rather than exposing the figure to the viewer’s desire, it invites the viewer to appreciate the discipline that makes beauty possible.

Touch, Revision, and the Evidence of Making

Look closely and the surface reveals revisions: a line adjusted at the shoulder, a wash pulled over an earlier red to soften it, a darker underpaint peeking through at the knee. These traces are not sloppiness; they are the record of the search for the exact balance of curve and color. The final image is crisp, but it contains within it the painter’s hesitations and corrections, the studio counterpart to the dancer’s rehearsals. Painting and dance become parallel practices, each aiming to fix a fleeting ideal through disciplined iteration.

Ornament and Abstraction at the Edge of Figure

The red ground, with its drifting white shapes, insists on a second reading: abstract pattern independent of figure. At moments the dancer seems to dissolve into this sea, especially along the tutu’s edge where lilac ruffles blend with coral. Elsewhere, strong contours pull her out again. The painting hovers at the edge between figuration and abstraction, a threshold that allowed Matisse to explore pure relationships without abandoning the human subject. The viewer’s eye oscillates between reading a person in a room and reading a field of interacting shapes and tones. That oscillation is the painting’s vital breath.

Historical Continuities and Transformations

In adopting the dancer as subject, Matisse also enters a lineage stretching from Degas’s ballet scenes to Renoir’s performers. Yet he transforms that tradition. Degas often explored the labor and awkwardness behind grace, Renoir the glow of flesh amid tulle; Matisse distills both into a heraldic clarity where the body is a sign and color is the main actor. The modernity lies not in novelty of subject but in the insistence that painting itself—its flatness, its color planes, its edges—can carry emotion without narrative elaboration.

Why the Painting Endures

“Dancer” endures because it concentrates many of Matisse’s lifelong concerns into a single, memorable figure. It shows how a room can be simplified into a field of sensation, how a body can be articulated by contour and costume, how pleasure can be sharpened by restraint. It also offers a generous vision of performance, one that respects the quiet professionalism behind spectacle. Each time the viewer returns, new relations disclose themselves: a cooler blue settling a hot passage, a black curve stabilizing a cloud of red, a scallop of tulle catching unexpected light. The painting is not an anecdote from 1925; it is an active structure that continues to tune the eye.

Conclusion

In “Dancer,” Matisse harnesses the theater of the 1920s to the decorative intelligence of his Nice studio. He composes a figure that is simultaneously emblem, person, and pattern, poised within a red world that shares her energy. The painting proposes that harmony is not calm for its own sake but a disciplined equilibrium alive with potential motion. Color sings; line conducts; pattern keeps time. The performer kneels, gathers her tutu, and waits for the cue. The picture, meanwhile, performs endlessly for the attentive eye.