Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

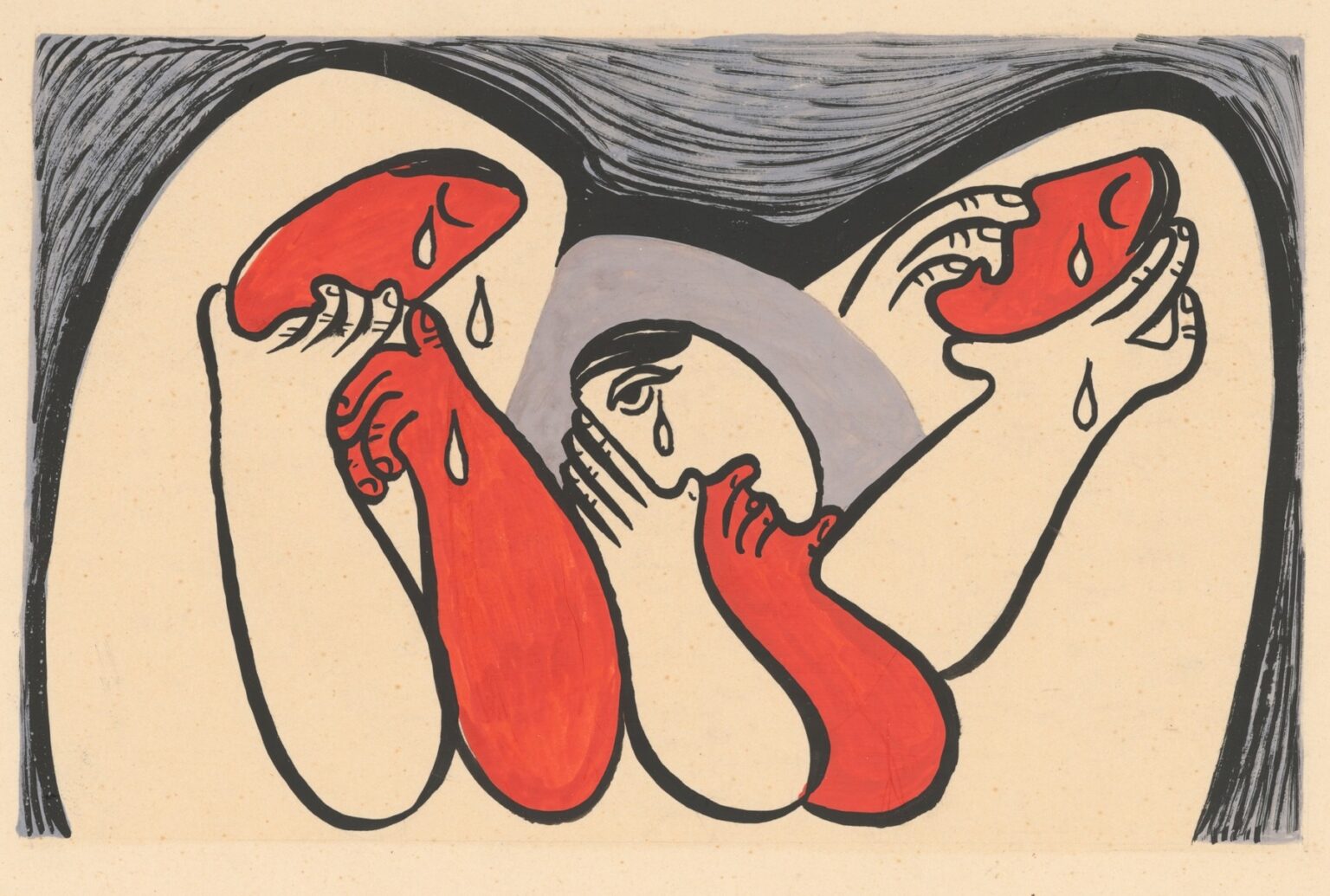

Mikuláš Galanda’s Crying Women (1938) presents a haunting yet tender study of collective sorrow through the spare elegance of modernist line and minimal palettes. In this drawing, three female figures—in a horizontal alignment—are united by the common act of weeping, their bowed heads and sheltered faces conveying profound grief. Executed in black ink and subtle gray washes on cream‑toned paper, the work eschews elaborate detail in favor of distilled form and raw emotional force. Each woman is rendered with an economy of strokes: the curves of her arms and the contours of her face merge into a seamless flow, while the tear drops—drawn as precise, teardrop‑shaped droplets—punctuate the composition with rhythmic repetition. Above their heads, a sweeping, hatching‑filled arch of black ink seems to bear down upon them like a mournful sky. Through this restrained yet expressive visual language, Galanda explores themes of vulnerability, solidarity, and the shared human experience of loss.

Historical Context

Created in 1938, Crying Women emerged at a fraught moment in Central European history. Czechoslovakia faced the imminent threat of Nazi annexation following the Munich Agreement, and the broader continent was teetering on the brink of global conflict. Artists across the region grappled with the specter of war, political upheaval, and the displacement of entire populations. In this tense environment, Galanda’s work shifted from earlier experiments with vibrant color and abstract form to a more introspective, graphic mode. His choice of a domestic, timeless subject—the act of women weeping—transcends immediate politics yet resonates deeply with the fears and anxieties of his time. By depicting figures in universal expressions of grief, Galanda both acknowledged the personal toll of historical turmoil and articulated a humanistic response that foregrounded empathy over ideology.

Galanda’s Late Period and Personal Circumstances

Mikuláš Galanda, born in 1895 in the Slovak town of Pezinok, had spent much of his career synthesizing international modernist trends—Cubism’s fractured planes, Fauvism’s vibrant hues, and Expressionist emotional intensity—into a uniquely Slovak voice. By the late 1930s, his own declining health—he was suffering from tuberculosis—sharpened his sensitivity to mortality and human fragility. Crying Women, one of his final major works, reflects this personal reckoning with vulnerability. The decision to depict women, traditionally cast as secondary or decorative figures, in the forefront of emotional narrative signals Galanda’s ongoing commitment to elevating marginalized voices. Here, the absence of background detail and the focus on gesture speak to an inward turn: the drawing becomes not a portrait of particular individuals but a universal emblem of suffering that bridges the personal and the collective.

Compositional Structure

Galanda employs a horizontal format to underscore the shared experience of the figures. The three women sit side by side, their forms overlapping just enough to suggest intimacy while remaining distinct. Their bodies follow a gentle arc: the leftmost woman’s bowed head flows into the central figure’s tilted shoulders, which in turn lead to the rightmost woman’s downward gaze. This rhythmic flow creates a visual continuity that carries the viewer’s eye across the page in a single, unbroken movement. Above, a heavy arc of hatching and swirling lines forms a canopy, pressing down like a burden of grief. Below, the stippled dots and light hatchwork at the women’s laps ground them in an abstracted space. The absence of a defined floor or walls lends the scene a psychological neutrality: the figures inhabit a realm of emotion rather than a physical location.

Use of Line and Form

In Crying Women, line is not merely a tool for delineation but the very substance of emotion. Galanda’s contours vary in weight: bold strokes define the outer silhouettes of arms and shoulders, while thinner lines articulate facial features, fingers, and tears. The figures’ arms curve in protective gestures—hands covering eyes, cheeks, or mouths—creating internal arcs that mirror the overarching canopy above. The tear drops, each precisely drawn, punctuate the fluidity of the human form with moments of crystalline clarity. These droplets, suspended yet evidently in motion, embody the tension between release and containment inherent in crying. Through this dynamic interplay of thick and thin, curved and straight, Galanda conveys a spectrum of feeling—from the quiet agony of private tears to the communal resonance of shared mourning.

Color and Tonal Restraint

Unlike his earlier, color‑rich experiments, Galanda here opts for monochrome restraint. The drawing relies on black ink, supplemented with pale gray washes in the central halo above the women’s heads and hints of gray in the rightmost shawl. This limited palette intensifies the emotional impact: the stark blacks evoke the weight of sorrow, while the unpainted cream of the paper serves as luminous counterpoint, suggesting the potential for consolation or transcendence. The gray halo, subtle yet distinct, frames the central figure and implies an aura of shared empathy or spiritual intercession. By forgoing any distracting hues, Galanda ensures that the viewer’s attention remains fixed on the purity of gesture and the stark geometry of grief.

Symbolism of Tears and Female Solidarity

Crying Women operates on multiple symbolic levels. The tear drops—seven around each face—might allude to the biblical “Seven Sorrows” or signal the completeness of sorrow experienced by each woman. Their stylized repetition transforms private tears into a communal chorus. The proximity of the figures suggests mutual support: although each woman weeps alone, they lean into one another, their limbs and shoulders intertwined. This solidarity becomes a potent counterpoint to isolation, portraying grief as a shared journey. In an era when women’s voices were often sidelined in public discourse, Galanda’s drawing asserts the moral authority of female experience: it is the women who bear witness to suffering, whose tears illuminate truths that might otherwise remain hidden.

Spatial Ambiguity and Psychological Depth

The drawing’s undefined background fosters a sense of psychological rather than physical space. The hatching canopy could represent storm clouds, the oppressive weight of history, or the enveloping swirl of emotional turmoil. Beneath, the stippled field might suggest earth, sand, tears collected on a floor, or even a pool of memory in which the women are immersed. This spatial ambiguity invites the viewer to inhabit the emotional landscape of the figures—to feel the pull of gravity and the buoyancy of empathy at once. The lack of perspective cues or horizon lines detaches the scene from any specific moment in time, elevating it to the realm of archetypal experience. In this way, Galanda creates a liminal space where personal grief becomes universal meditation.

Gender, Identity, and the Role of the Woman in Modernism

Galanda’s choice to depict women as the central subjects of Crying Women reflects his broader engagement with questions of gender and social identity. Within the male‑dominated modernist canon, female suffering was often relegated to symbolic or decorative roles. In contrast, Galanda foregrounds women’s emotional complexity and moral agency. Their weeping is not a sign of weakness but an act of truth‑telling: tears speak where words fail. This representation aligns with contemporary Slovak women’s increasing public engagement in social and political movements, including suffrage and pacifism. By giving women’s grief visual weight and moral resonance, Galanda challenges reductive stereotypes and invites a reevaluation of the feminine within both art and society.

Technical Execution and Medium

Working in pen and ink with selective washes, Galanda demonstrates remarkable control over his medium. The ink’s deep black saturates the canopy above and the contours of the figures, while allowing for gradations in line density. The gray washes—applied sparingly—create a focal halo effect without obscuring the pen work beneath. The paper’s warm tone, speckled with natural fibers, adds a tactile dimension that contrasts with the crispness of the ink. Observation of the surfaces reveals subtle variations: slight feathering where ink meets paper grain, variations in wash intensity where brush dipped into differing pigment concentrations. These technical nuances contribute to the drawing’s overall vitality and underscore Galanda’s mastery of graphic techniques.

Comparative Modernist Perspectives

In the broader context of 1930s European art, Crying Women shares affinities with both Expressionist and socially engaged art. Its emphasis on psychological truth and emotional intensity recalls the works of Käthe Kollwitz, whose prints of women suffering losses in wartime Berlin became iconic. Yet Galanda diverges by incorporating modernist abstraction: his figures are not anatomically precise but stylized to convey universal archetypes. Unlike the Surrealists, who delved into dream logic, Galanda remains anchored in the tangible bodily gestures of grief. His work thus occupies a unique niche at the intersection of humanist realism and lyrical abstraction—embracing emotional authenticity while harnessing the power of simplified form.

Legacy and Enduring Significance

Though Mikuláš Galanda’s life was cut short by tuberculosis in 1939, Crying Women endures as one of his most powerful late‑career statements. The drawing’s poignant blend of empathy, formal innovation, and social relevance positions it as a touchstone of Slovak modernism. In subsequent decades, Galanda’s graphic works inspired younger generations to explore the expressive potential of line and the moral weight of subject matter. Exhibitions of 20th‑century Slovak art frequently feature Crying Women to illustrate the region’s engagement with European avant‑garde movements and its capacity for original, resonant contributions. Today, the drawing continues to speak across cultures and eras: its portrayal of sorrow and solidarity resonates wherever communities confront collective trauma and seek healing through shared mourning.

Conclusion

In Crying Women, Mikuláš Galanda achieves a sublime synthesis of formal economy, emotional depth, and social witness. Through his skillful use of line, his restrained tonal palette, and his empathetic portrayal of female subjects, he transforms a simple drawing into a profound meditation on grief, unity, and the human capacity for compassion. The work’s spatial ambiguity and symbolic richness invite viewers into a space of shared reflection, where tears become visible bonds between individuals and between the artwork and its audience. As a culminating testament to Galanda’s late period, Crying Women affirms the enduring power of modernist art to bear witness to suffering while fostering solidarity and hope.