Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

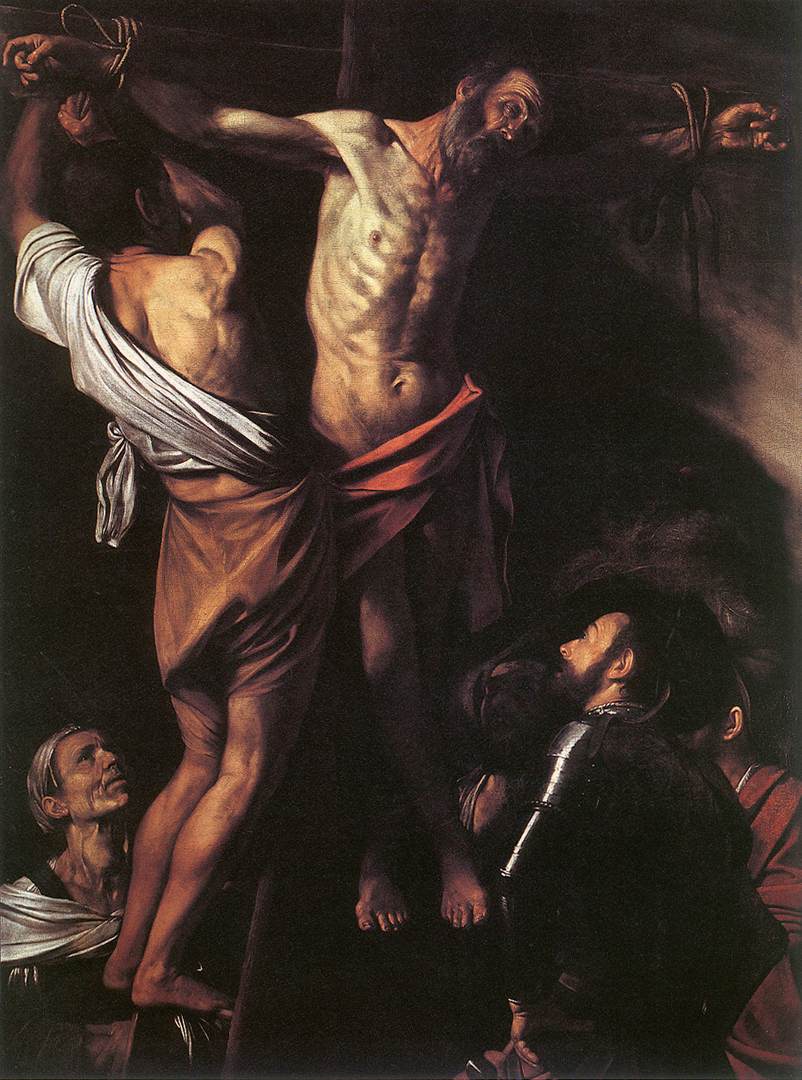

Caravaggio’s “Crucifixion of Saint Andrew” (1607) is a drama of bodies hauled into revelation by light. In a cavern of darkness, the apostle is raised on his cross while executioners strain at ropes and the crowd gathers below. The scene is not a distant pageant but an event unfolding at arm’s length. Everything that makes Caravaggio decisive for European painting is present here: radical tenebrism, ruthless realism, a choreography of diagonals that pulls the eye through conflict toward meaning, and a tenderness for mortal flesh even when it is stretched on the instruments of death. The result is a Passion narrative in miniature, where martyrdom becomes a study in attention, will, and grace.

The Historical Moment And Caravaggio’s Neapolitan Phase

Painted during Caravaggio’s first Neapolitan sojourn after his violent flight from Rome, the canvas belongs to the period when his style contracted to essentials. The artist had learned to distill story into gesture, to exchange elaborate settings for blackness that behaves like architecture, and to let light operate as a judge. Naples rewarded this clarity. Patrons wanted devotional force rather than decorative flourish, and Caravaggio delivered it by stripping away anecdote. “Crucifixion of Saint Andrew” embodies that late resolve: five figures, one cross, a slot of space, and a beam of illumination are sufficient to ground theology in muscle.

Composition As A Spiral Around The Cross

The composition turns on an X-shaped geometry created by the apostle’s spread arms and bent legs set against the diagonal thrust of the men raising him. At the center of this dynamic is the rough timber of the cross, a vertical and horizontal that the painter partly hides so the body carries the visual load. The eye enters at the lower right where a soldier in armor looks up, rides the diagonal of Andrew’s torso toward the left arm bound by rope, returns down the arc of the executioner’s twisting back, and then climbs again along the rope that bites into Andrew’s right wrist. The movement is a spiral—rise, descend, rise—that mimics the physical act of hoisting a heavy body and the spiritual ascent that martyrdom implies.

Tenebrism That Judges Rather Than Decorates

Light enters from the upper left and strikes Andrew’s ribcage, abdomen, and head with an almost clinical clarity. It catches the taut cords in the executioners’ forearms, the glint on a cuirass, and the weathered planes of a woman’s face at the lower left. Everything else collapses into a brown-black that thickens like smoke. This is not theatrical shadow for its own sake. It is a moral instrument. The light makes visible the dignity of the victim and the agency of his handlers; the dark mutes distraction and turns the space into a tribunal where the eye must decide what matters.

Saint Andrew’s Body As A Text To Be Read

Caravaggio writes the martyrdom in anatomical sentences. The sternal notch opens as Andrew cranes his neck toward heaven; the serrations of the rib muscles flash under the skin; the abdominal wall tightens as his pelvis rotates against the ropes; the toes flex, seeking ground that is disappearing beneath him. None of this is generalized heroics. It is the persuasion of close observation. The saint’s face is not transported beyond the moment; it is attentive, questioning, and finally consenting. The mouth is parted as if to answer, the brow contracted in concentration more than agony. Ecstasy here is not evasion but heightened presence.

The Executioners And The Banality Of Force

Three men do the work of hoisting and binding. Caravaggio refuses to turn them into caricatures. The figure at left twists his torso, the shoulder blade cutting a hard ridge under skin as he braces and pulls. The crouching man at lower center grips the cross’s base with one hand and adjusts a rope with the other, a laborer’s pragmatism unclouded by hatred. At the right, a compact assistant leans his weight into the timber. These are not monsters; they are efficient. The painter’s realism prevents easy moralizing and therefore deepens the ethical shock: atrocity can be executed by ordinary bodies concentrating on a task.

Witnesses And Our Station In The Scene

Two witnesses puncture the circle of labor. At the lower right a soldier in polished armor and a broad-brimmed hat raises his face toward the saint; his gleaming breastplate mirrors the light, turning secular authority into an unwilling reflector of sanctity. At the lower left an elderly woman lifts her gaze as if to receive, not to interfere. Her face is a landscape of faith and fatigue. These witnesses teach viewers where to stand: close enough to feel the strain in the ropes, humble enough to look up.

Gesture, Gaze, And The Moment Chosen

Caravaggio seizes the instant when the cross is not yet fully planted. Andrew’s arms are bound, his legs still searching; the executioners are mid-effort, muscles firing; the witnesses have not yet broken into lament. The event has not congealed into symbol; it is still action. The saint’s gaze is crucial. He looks beyond the men who hold him and beyond the viewer, twisting the neck toward a light source that also serves as theological destination. His seeing gives the composition its orbit. The other faces turn because he turns; their gestures are gravitationally pulled by his orientation.

Color As Emotional Weather

The palette is concentrated and sober: earth umbers, the waxen tones of skin, a handful of whites in cloth and glancing armor, and a brick-red loincloth that binds the saint’s middle with a note of warmth. Color here does not argue; it supports. Flesh tones are modelled with minute temperature shifts—cool violet-gray in shadow, warmer ochre lights along planes that receive the beam. The restraint of color forces the viewer into the realm of value contrasts, where meaning becomes a function of how much a surface holds light.

Space Reduced To Conscience

There is nearly no background—only a wall flattened by darkness and the implied floor where the cross’s base will soon thud. This scarcity of setting turns the black into a moral field, an emptiness against which every action reads with intent. The viewer cannot escape into scenery; we must decide what the upward turn of Andrew’s head signifies and what the ordinary competence of his handlers demands of conscience.

The X-Shaped Cross And The Iconography Of Andrew

Tradition holds that Andrew was crucified on a diagonal cross, the saltire that later adorns flags and altars. Caravaggio hints at that form without illustrating it diagrammatically. He lets the body mark the X with outstretched arms and cranked hips while the timber itself remains barely legible. The choice keeps the focus on the person rather than the device. Iconography is honored through anatomy rather than design, a thoroughly Caravaggesque solution that fuses symbol with flesh.

Comparison With The “Crucifixion of Saint Peter”

Caravaggio had painted another aged apostle lifted onto wood a few years earlier. In the “Crucifixion of Saint Peter,” the cross is being raised upside-down; the workmen strain at the base in a dense knot of legs and backs. In the “Crucifixion of Saint Andrew,” the space opens, the figure of the saint bears more light, and the diagonal is less brutal and more ascensional. Both pictures honor labor, but Andrew’s bears a different spiritual temperature—less heaviness, more disclosure. You sense an acceptance emerging in real time, visible in the twist of the neck and the slight release at the mouth.

Brushwork, Layers, And The Persuasion Of Paint

The surface shows Caravaggio’s late economy. Transparent darks are laid in to establish mass; midtones are floated in with semi-opaque passages; flashes of bodycolor articulate tendons, knuckles, and edges of cloth; warm glazes enrich the deepest shadows. There is an alternation of crisp and lost edges: a tight contour at the saint’s forearm where rope bites; a softened threshold where abdomen rolls into shadow; a nearly evaporating outline along the right-hand executioner’s shoulder. These choices guide attention invisibly. You read the exact story he wants you to read because the paint insists.

The Theology Encoded In Posture

Andrew’s bodily arc is a kind of doctrine. The pelvis rotates toward the viewer, vulnerable; the chest lifts as if to receive; the head tilts back toward light that is both pictorial and metaphysical. The executioners’ energies run horizontally and downward, utilitarian; the saint’s energy runs upward, receptive. Caravaggio does not need clouds, angels, or inscriptions. He lets posture carry belief. The saint is not passive; he is actively consenting. That consent is the hinge of the painting, the quiet engine that dignifies violence without excusing it.

The Ethics Of Representation

There is no gore. The ropes abrade; the muscles pull; the skin puckers where bonds dig; but Caravaggio refuses the theatrics of blood. The horror is persuasive precisely because it is not sensational. Viewers feel implicated rather than entertained. The painter’s compassion for the body shapes the entire rhetoric of the image: to see a ribcage is to be reminded of breath; to look at a bound wrist is to feel one’s own. The painting turns anatomy into sympathy.

The Soldier’s Armor And The Mirror Of Light

The polished cuirass at the lower right is a small essay in reflection. It receives the same beam that reveals the saint and throws back a hard, cold sheen. The effect is double: worldly power is shown to be derivative, dependent on the light it cannot generate; and the viewer gets a subtle reminder that metal, not just flesh, is under scrutiny. The soldier is not reduced to a villain. He is a man caught between shine and shadow, a witness whose armor betrays him by reflecting a sanctity he may not recognize.

The Old Woman And The Church Below The Cross

The weathered woman at the lower left, neck tendons taut as she looks up, gives the painting its ecclesial register. She stands for the community that lives under martyrdom’s shadow and hope. Her gaze is attentive rather than hysterical; her presence prevents the scene from collapsing into a duel of aggressors and victim. With her, the Church is present—not triumphant, not yet consoled, but faithful and watchful. She anchors the composition emotionally, the way the cross’s base anchors it physically.

The Viewer’s Engagement And The Space Of Devotion

Caravaggio places the scene close to the picture plane, as if we are one step from the men handling the ropes. We feel the weight of timber and the scrape of wood. The proximity is not a stunt; it is an invitation to devotion. The painting wants contemplation of a kind the Baroque perfected: not a distant gaze but a witness’s attendance. To stand before it is to take a position among the figures—either to add your strength to the lift, to fall into the soldier’s curious regard, to join the woman’s steadfast looking, or to align your breath with Andrew’s upward turning.

Naples, Relics, And The Power Of Martyrdom

Neapolitan devotion to saints and their relics saturated the culture into which this painting entered. Caravaggio’s realism makes that devotion newly immediate. He paints Andrew not as a legend but as a present-tense body whose bones might one day be enshrined in the very city that contemplates him. The painting functions as both narrative and prelude: it shows the making of a martyr and, by implication, the birth of a cult of remembrance. The dark around the figures becomes a reliquary of air.

Why The Painting Still Matters

“Crucifixion of Saint Andrew” speaks wherever power is applied professionally and the vulnerable choose dignity rather than rage. It understands that evil often looks like competence. It also understands that sanctity looks like attention—seeing the light, orienting the body toward it, consenting to truth even when it costs. The painting trains the eye to recognize those realities in our own rooms.

Conclusion

Caravaggio’s image is not a summary of death; it is a poised beginning, the instant when wood and will join. Around an X-shaped body he arranges a ring of human intentions: work, authority, witness, consent. Light assigns each its weight. By refusing spectacle and trusting gesture, he harvests from the simplest means a vision of martyrdom both terrible and consoling. To stand before this canvas is to feel the upward tug of Andrew’s gaze and the inward demand of his consent. The darkness will swallow everything except what the light insists on keeping: the truth of a human body turned toward God.