Image source: artvee.com

Introduction: Painting as Poetic Topography

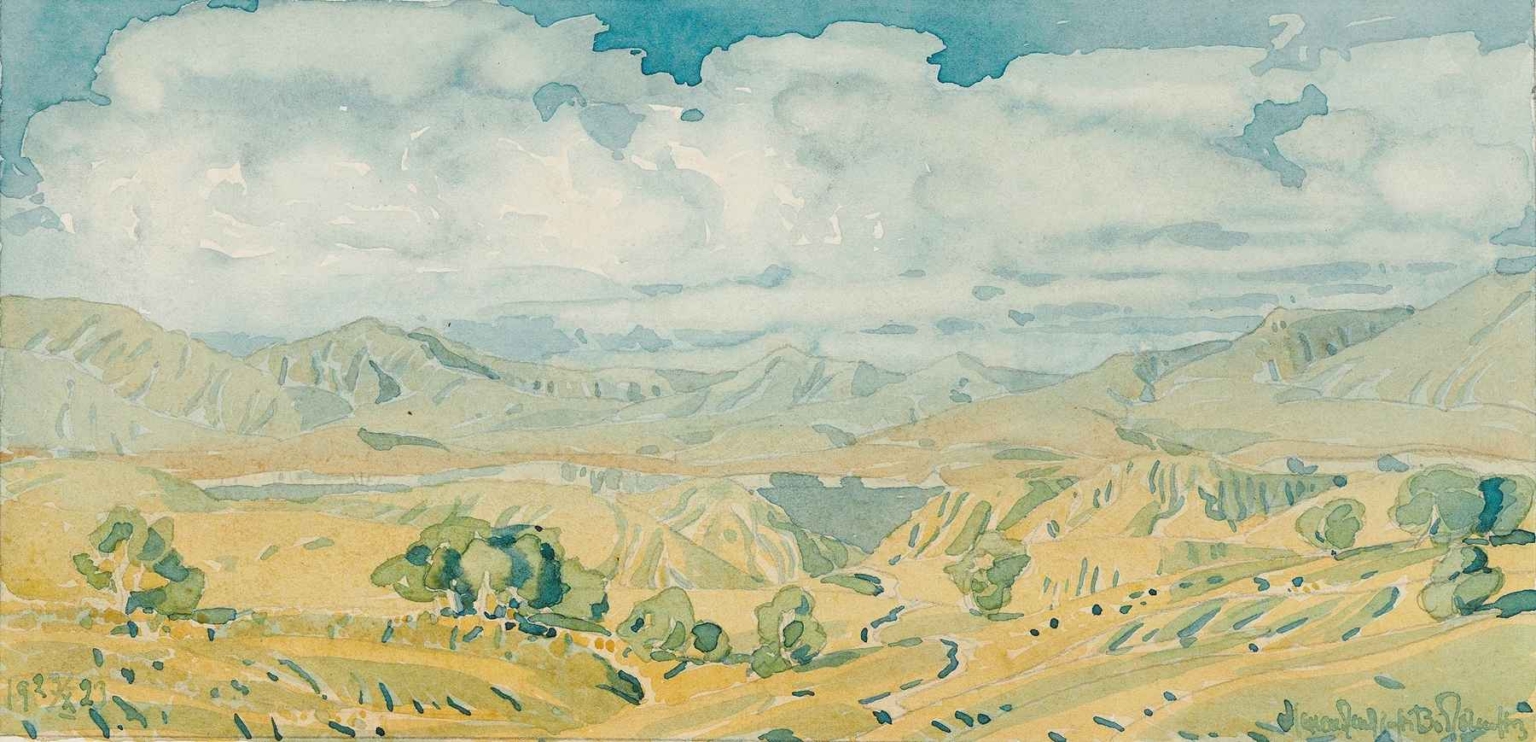

Maksimilian Voloshin’s Crimean Landscape is more than a visual document of a region—it is a contemplative distillation of the land’s metaphysical essence. Rendered in pale washes and stylized brushwork, this watercolor evokes a rhythmic, almost musical interpretation of the hills and valleys of Crimea. Painted in 1923, the work straddles traditional observation and symbolic abstraction, inviting viewers not just to look, but to feel the terrain’s ancient silence and spiritual clarity.

Voloshin was not only a painter but also a celebrated poet and thinker, deeply entwined with Russian Symbolism. His works—whether written or painted—reflect a lifelong fascination with the landscape of Crimea, which he saw as a metaphysical frontier between East and West, history and nature, life and afterlife. Crimean Landscape stands as a visual poem, mapping both physical terrain and emotional depth in a language of gentle washes and luminous color.

This analysis explores the formal structure, chromatic subtlety, poetic sensibility, and symbolic undertones of the painting while situating it in the artist’s broader intellectual and cultural milieu.

Artist Background: Maksimilian Voloshin and the Crimea of the Mind

Maksimilian Voloshin (1877–1932) was one of the most intriguing figures of the Russian Silver Age. A poet, essayist, translator, mystic, and visual artist, he embodied the archetype of the multidisciplinary visionary. Voloshin’s house in Koktebel became a cultural salon frequented by writers such as Marina Tsvetaeva, Osip Mandelstam, and Andrei Bely, and he spent much of his adult life meditating on the metaphysical significance of landscape, especially the rugged geography of Crimea.

For Voloshin, the Crimean Peninsula was not merely a backdrop, but a central protagonist in the human narrative. Its ancient hills, wind-carved cliffs, and sunlit plateaus served as emblems of transformation and transcendence. He painted hundreds of landscapes in watercolor, often outdoors, treating them as both artistic studies and spiritual exercises. Crimean Landscape, dated 1923, is a product of this period of synthesis between aesthetic simplicity and mystical reflection.

Composition: Geography Abstracted into Rhythm

The composition of Crimean Landscape is panoramic yet meditative. Rather than focusing on a single prominent feature, Voloshin opens the entire canvas to the horizon, stretching the eye across undulating hills, softly eroded ridges, and valleys marked by sparse vegetation. There is a clear recession from foreground to background, but spatial depth is achieved not through linear perspective but through rhythmic layering of color fields.

Foremost are golden hills in varying hues of ochre, yellow, and dusty beige. Their contours curve gently, outlined by thin blue lines that recall both traditional Japanese woodcuts and Art Nouveau sinuousness. In the distance, a ribbon of deep blue water—perhaps a river or inlet—cuts a horizontal axis across the canvas. Behind it rise misty, subdued mountains rendered in blue-gray.

Above all this, the sky is given ample space, filled with simplified cumulus clouds and patches of pale, sun-washed blue. The overall effect is one of levity and openness, with each formal element reinforcing the painting’s meditative tone.

Watercolor Technique: Transparency and Intuition

Voloshin’s watercolor technique is restrained, lyrical, and evocative. His brushwork is minimal and calligraphic. He avoids layering or overwrought detail, preferring to allow the white of the paper to speak between washes. This lends the painting an airy transparency that mirrors the spacious light of southern Crimea.

Colors are applied in translucent veils: pale ochres for the earth, blue-greens for the foliage, soft grays and violets for the distant terrain. The sky is especially deft, with clouds rendered not by pigment but by negative space—unpainted areas shaped by the blue surrounding them. This approach is both economical and expressive, reinforcing the artist’s preference for suggestion over delineation.

Lines, used sparingly, function more like musical notations than structural boundaries. They define forms without imprisoning them. The landscape breathes and flows, an organic field of sensation rather than a rigid geographic transcription.

Palette: Earth and Air in Equilibrium

The color palette in Crimean Landscape reinforces the painting’s sense of harmony and spatial breath. Voloshin chooses warm yellows, cool blues, soft greens, and desaturated browns to evoke the dry, sun-drenched character of the steppe and foothills. These tones are subdued but deliberate, lending the painting an atmosphere of clarity and repose.

The use of color is symbolic as well as representational. Yellow is often associated with divine light and spiritual clarity; here it dominates the foreground, bathing the hills in a sense of metaphysical warmth. Blue, traditionally linked with the infinite and the eternal, forms the backdrop in both water and sky. Together, these opposites—earth and sky, body and spirit—are held in perfect equilibrium.

This chromatic balance is key to the painting’s emotional resonance. Nothing jars. Everything flows. Color becomes a medium of calm, a quiet liturgy unfolding across the page.

Atmospheric Presence and Emotional Tone

The painting exudes serenity. There is no movement, no storm, no spectacle—only light and stillness. Yet it is not static. The subtle undulation of the hills and the floating nature of the clouds imbue the scene with a gentle inner rhythm. It is as if time itself has slowed, and the viewer is granted access to a moment of sacred suspension.

Voloshin was drawn to such moments, where landscape becomes a mirror for the soul. Crimean Landscape offers not an escapist fantasy but a kind of contemplative realism—an inner geography made visible. The viewer is invited not to admire from afar, but to enter, dwell, and attune.

There is also a sense of absence in the work. No human figures, no ruins, no narrative markers. This absence enhances the mystical tone. The land is eternal, indifferent to the fleeting drama of history. It exists in its own sovereign temporality, one that humbles and soothes the human gaze.

Symbolism and Metaphysical Resonance

Though Crimean Landscape can be appreciated purely as a formal and technical exercise, it carries layers of symbolic meaning. Voloshin, steeped in theosophy, mysticism, and Russian Symbolist philosophy, saw landscape as a living presence—a bearer of archetypes and spiritual truths.

In this context, the painting becomes a meditation on the relationship between earth and heaven. The land, painted in luminous yellows and ochres, symbolizes grounded reality—life, memory, history. The sky, open and pale, represents transcendence—mind, imagination, the divine. The mountains in between form a liminal zone, a bridge between the visible and the invisible.

Voloshin often wrote of Crimea as a “place of thresholds,” where East and West, ancient and modern, material and immaterial intersect. This painting reflects that belief. Its formal clarity hides a metaphysical depth, making it both a landscape and a mantra—a visual chant grounded in line and light.

Voloshin’s Visual Poetics: A Crossroads of East and West

Voloshin’s visual style draws upon both Western and Eastern traditions. His compositional balance and tonal restraint echo the 19th-century European watercolorists, such as Turner or Corot. Yet his economy of line and meditative quietude also recall Chinese landscape scrolls and Japanese ukiyo-e prints.

This synthesis is not accidental. Voloshin believed in a pluralistic, holistic vision of art and culture. Crimean Landscape reflects this ideology. It is a place where diverse visual languages converge into a singular aesthetic voice—one that values nuance over clarity, intuition over didacticism.

Moreover, the painting’s blend of realism and abstraction anticipates modernist trends to come. It lacks the heavy brushwork and emotional immediacy of Expressionism, yet it shares that movement’s interiority. It is not modernist in form, but it is unmistakably modern in spirit—a painting that seeks to convey presence, essence, and being.

Historical and Cultural Context

In 1923, when this painting was signed, the world Voloshin had known was vanishing. The Russian Revolution had swept away the old intelligentsia, and Crimea itself had become a contested zone. Amid political turmoil and ideological repression, Voloshin continued to paint landscapes and write poetry, believing in the redemptive power of nature and personal expression.

In that sense, Crimean Landscape is not only a depiction of place, but a quiet act of resistance. It affirms the permanence of natural form in the face of historical rupture. It asserts that beauty, order, and clarity can still be found—even when civilization fractures.

This makes the painting doubly powerful. It is a balm and a statement, a retreat and a reaffirmation of enduring values.

Conclusion: A Landscape Beyond Geography

Crimean Landscape by Maksimilian Voloshin is a rare achievement: a landscape that transcends geography to become an icon of spiritual space. With its minimal lines, glowing palette, and quiet geometry, it evokes not only the terrain of Crimea, but the timeless territory of contemplation.

The painting does not overwhelm. It does not seek to impress. Instead, it draws the viewer inward—into rhythm, into silence, into communion. It reminds us that the land, in its simplicity, can be a source of revelation. And it affirms Voloshin’s belief that art must strive toward clarity, openness, and spiritual anchoring.

In a world saturated with noise and image, Crimean Landscape stands as a testament to the enduring power of less. Less pigment, more space. Less narrative, more being. It is a painting that asks for quiet—and rewards it with peace.