Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction: The Architect of Image, Seen Without His Stage

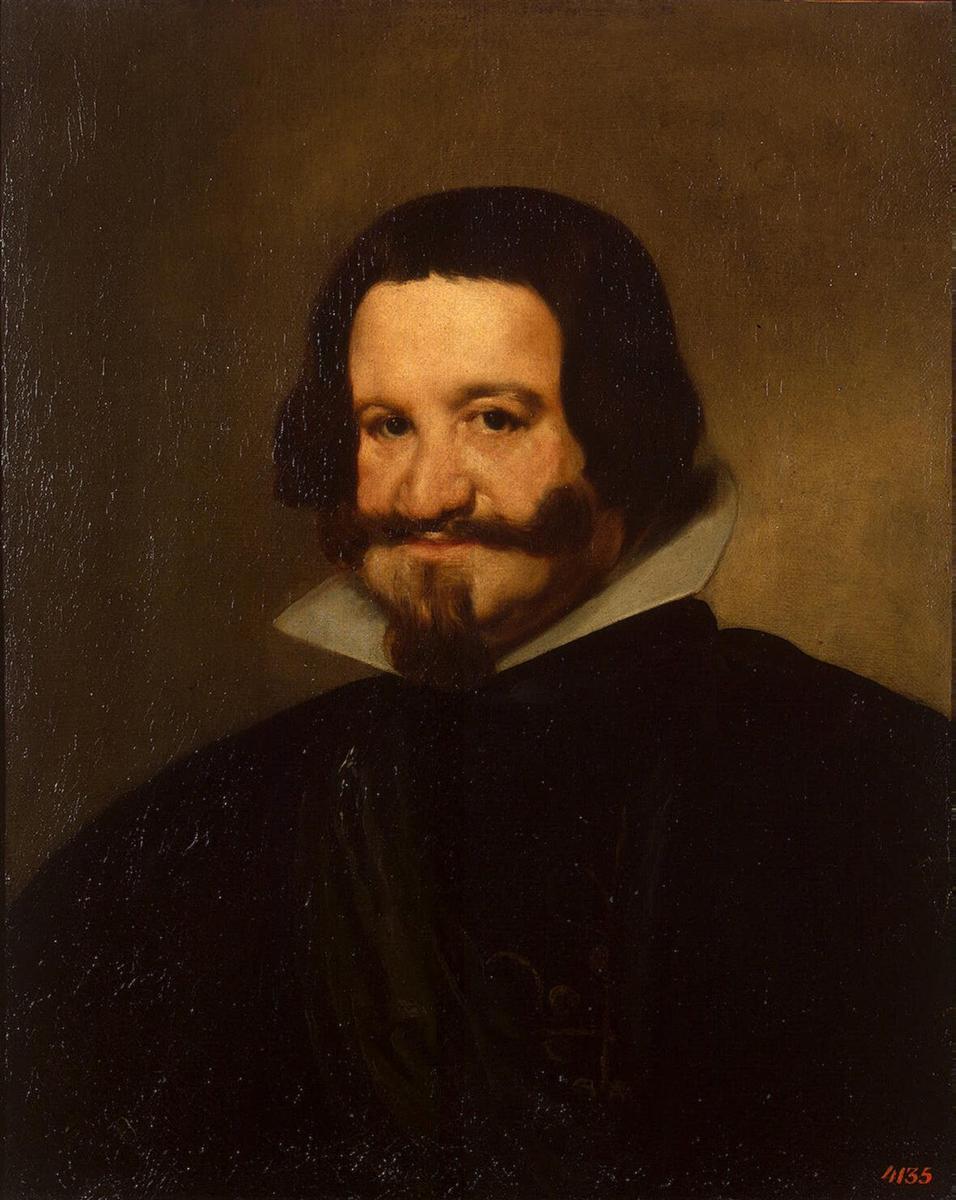

Diego Velázquez’s “Count-Duke of Olivares” presents Spain’s most powerful minister not as a thundering statesman presiding over cavalry and ceremony, but as a man in air and light. The face is frontal and very near, cropped at the shoulders so that brocade, baton, and banners cannot compete with the alert weight of the eyes. The dark mass of the coat receives light only in quiet gleams; the stark white of the ruff frames the head like a bracket. The famous moustache and pointed beard, trained into courtly arabesques, carry a touch of theatrical flourish, yet the expression is not staged. It is the look of a mind that measures rooms and moments before it speaks. Velázquez, who fashioned the visual rhetoric of the Habsburg court, here subtracts pageantry to let psychological gravity do the work. The result is a portrait that refines power into presence.

Historical Background: A Minister Who Became a Myth

Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares, dominated the reign of Philip IV. He choreographed royal spectacle, reformed finances and the army, patronized culture, and centralized authority with relentless ambition. He is the rider in Velázquez’s equestrian triumphs, the master of jousts and ballets, the impresario of the Buen Retiro. Yet by the late 1630s his project strained under war and debt; admiration and resentment gathered in equal measure. Painting the Count-Duke at close range, Velázquez does not rehearse achievements or controversies. He offers a human core behind the public myth, where calculation, fatigue, intelligence, and appetite converge in the particular architecture of a face.

The Courage of Cropping: Power Without Paraphernalia

Many state portraits depend on stagecraft—columns, carpets, heraldry—to broadcast rank. Velázquez limits himself to a head and shoulders against a breathable ground, asking the visage to carry what the emblems usually shout. The decision is bold. It risks diminishing the sitter’s magnificence; instead it concentrates it. The minister’s authority arrives through expression, not accessories. Because the composition withholds the easy guarantees of status, we read character more sharply: a man accustomed to command, confident in display, but wary enough to look sidelong at the viewer as if testing our measure in return.

Light and Tone: A Theater Made of Air

Light falls from above left, soaking the forehead, cheek, and the upper planes of the moustache and beard, then dwindling into the hushed blacks of cloth. The ruff ignites as an intense, cool highlight, controlling the value range and giving the face a stage on which to emerge. Velázquez’s tonal architecture is restrained yet decisive: high key for flesh and collar, deep key for garment and ground, mid key for background that moves from warm olive to a faintly grayish tan. The face thus floats forward without ever feeling cut out. Air connects everything; we sense the small glints of moisture on the lower lip and the damp sheen in the eye because the atmosphere is credible.

Color Harmony: Blacks that Aren’t Black

The palette appears Spartan—flesh notes, white, a near-monochrome garment, and a warm neutral ground—but within those limits the chromatic play is rich. What reads as black is a compound of cool blues, bruised greens, and wine-dark browns. The coat’s surface absorbs light and then returns it as slow glows that keep the picture from flattening. The collar’s white contains faint grays and biscuit warms, preventing the shock of chalk and letting the face hold the high note. A tiny crimson ember flushes the lower lip; warm highlights punctuate the moustache. The harmony is sober yet alive, appropriate to a figure who staged splendor while dressing himself in Castilian gravity.

The Face as a Map of Resolve

Velázquez models the head with sculptural conviction. The forehead is broadly lit, smooth yet not polished away; the brow line has energy but no theatrical frown. The nose sits proud and straight, catching a firm highlight at the bridge. The moustache curves with the precision of trained hair, lifting at the ends like a tilde over the mouth; it does not obscure the speech beneath. The beard narrows to a point that reiterates the chin’s resolution. Most telling are the eyes. They do not simply face us; they approach from an angle, registering both audience and flank. The look carries wit and calculation, a quiet sense that the sitter is more interested in the viewer’s intentions than in his own image. It is a gaze designed to govern rooms.

Brushwork: Economy that Persuades

Up close, Velázquez’s touch is confident and economical. The ruff is not woven lace; it is a handful of cool impastos and crisp edges that the eye converts into linen. The moustache is a few gently curved strokes, each one a fluent sentence fragment that the viewer’s perception assembles into hair. Flesh is built from warm and cool patches that shift like weather across bone and muscle—no blending for its own sake, only as needed to articulate form. The coat is a field of deep tones broken by a few slow, oily highlights. This economy confers authority. We feel the painter’s certainty, and by extension we credit the subject’s.

Rhetoric of Restraint: Majesty Without Monumentality

The portrait is intimate in scale, but it does not belittle. By refusing monumental trappings, Velázquez proposes a different rhetoric of majesty: steadiness, candor, and cultivated self-command. The Count-Duke had a genius for spectacle and a taste for excess; the painter replies with reduction, as if to rescue the statesman from his own propaganda. Even the famous moustache—so often an emblem of swagger—becomes a structural curve tying cheek to cheek across the mouth, more architectural than theatrical. The message is clear: true power can afford quiet.

The Collar: Geometry that Frames Intellect

Spanish collars in Velázquez’s portraits operate like proscenium arches. Here the starched ruff rises behind the jaw in two triangular wings. Their geometry is crisp enough to be almost abstract. They lift the head, set it off from the torso, and ensure that the face commands the field. The white reflects light back into the shadows under the chin, modeling the flesh with secondary illumination. Symbolically the collar reads as discipline—rules holding temperament in place—but it is also humane: a body is supported, not strangled. Velázquez never lets emblem overrule anatomy.

Psychology in the Mouth and Brow

The Count-Duke’s mouth is decisive. The upper lip is thin but full enough at center to suggest appetite; the lower lip is a small cushion pressed by the moustache’s weight. A fraction of a smile may hover, but it is not sociability; it is satisfaction allied to watchfulness. The brows are set neither high in surprise nor low in threat. They relax into an arc that indicates a temperament practiced at listening and then moving. Velázquez avoids the caricature of cruelty that enemies later fastened on Olivares. He chooses instead the more challenging task of making formidable intelligence legible without falling into flattery.

A Portrait in Dialogue with Its Equestrian Counterpart

Placed next to the cinematic “Equestrian Portrait of the Count-Duke of Olivares,” this head reads like the backstage truth that empowers the show. In the grand canvas, he pilots a rearing horse, baton raised, banners flying—Spain’s pageant distilled. In this smaller painting, baton and horse are gone; what remains is the mind that conceived such theater. The two works form a pair of complementary theses: power as public choreography and power as private clarity. Velázquez excels at both registers, and here the second is more radical for its refusal of noise.

The Ground: A Modern, Breathable Space

The background is a continuous field of warm neutral, subtly modulated from left to right. No curtain, column, or cartouche encroaches. The plain space is modern; it anticipates studio portraiture’s preference for neutral grounds that amplify personality. Within the seventeenth-century court, such simplicity reads as confidence. The painter does not need to name location or display artifacts of rank; he trusts the face to carry identity. That trust invites the viewer’s attention to settle where it matters.

The Ethics of Seeing: Equality of Light

Velázquez painted kings, jesters, dwarfs, and ladies with the same impartial light. This consistency is not a political program; it is an artistic ethic. In this portrait, the light that models Olivares’s forehead is the same that illumines Pablo de Valladolid’s gesture or Lezcano’s contemplative brow. The effect is leveling without diminishing rank: all subjects are granted the dignity of truthful air. For a minister who organized spectacle to legitimize rule, being painted in that honest light amounts to a quiet absolution from the noise of propaganda.

Time and the Trace of a Life Lived in Offices

The flesh bears the record of labor. Subtle heaviness under the eyes speaks of work and wakefulness; a certain flush on the cheek hints at appetite and health; the set of the jaw suggests habits of decision. Velázquez paints none of this emphatically, but it surfaces naturally from the truthful handling of value and edge. A life of councils, audiences, and writings accumulates in this skin. The portrait does not sentimentalize fatigue; it records the cost of governing as texture.

The Viewer’s Position: An Audience of One

We meet the Count-Duke at conversational distance, not the oblique, elevated vantage of throne rooms. That proximity encourages a complex response: respect tempered by recognition of the human scale. The sitter’s gaze acknowledges us, yet keeps a portion of attention withheld. It is a dynamic common to Velázquez’s finest portraits—the subject is present but not possessed. We share air with power without being crushed by it.

The Moustache as Calligraphy and Mask

The Habsburg court loved intricate facial hair. Here the moustache’s curves are perfect calligraphy, each twist echoing the flourishes of royal signatures and festival scrolls that Olivares commissioned. As mask, it announces masculinity and pride; as paint, it becomes a set of dark ligatures tying the face together. Velázquez acknowledges the theatricality while grounding it in hair’s real behavior—thicker at the base, catching small highlights where wax or oil smooths strands. The moustache therefore reads both as emblem and as matter, a balance the painter sustains throughout.

Comparisons with Other Heads by Velázquez

Placed among Velázquez’s head-and-shoulder studies—such as the intimate images of Philip IV or the penetrating “Juan de Pareja”—this portrait shares the artist’s preference for brevity and punch. Each physiognomy receives a distinct rhythm of brushwork. In Olivares, the strokes are assured but measured, befitting a temperament of control. In Pareja, they are more elastic, celebrating resilience. The comparisons highlight Velázquez’s unparalleled ability to let technique behave like temperament.

The Silence of Authority

The portrait emits a particular silence: the silence of someone who has already made arrangements. There is no furrowed rhetoric, no pleading for admiration. The slight turn of the head, the calm in the brow, the level mouth all say that the sitter is accustomed to moving levers unseen by others. Velázquez captures that interior stillness without coldness, allowing warmth to persist in the cheek and eye. Authority here is not noise but condition.

Why the Image Endures

Images of power often expire with their regimes. This one persists because it translates rank into a universal: the human face thinking. Restoration or modern viewers may not share Olivares’s politics, but they recognize the alert composure of a person balancing projects and risks. The portrait’s means—natural light, restrained color, decisive brush—are perennially convincing. The great horseman of court ceremony is reintroduced to history as a mind. That is Velázquez’s gift.

Conclusion: Presence as the Ultimate Emblem

“Count-Duke of Olivares” proves that the most persuasive emblem of power is neither baton nor banner, but presence rendered honestly. By setting the minister close against a quiet ground and letting light speak, Velázquez distills a career of spectacle into a single, memorable gaze. The face is not flattered; it is respected. The whites are not blinding; they steady the head. The blacks are not void; they breathe with hidden color. In this balance of restraint and vitality, the painter invents a language for portraying authority that remains modern: show the person, and the office will be understood.